Poems by Dion O'Reilly

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

Band-tailed Pigeon

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Summer 2020

Dion lives in the Soquel Creek watershed on a stream-cut terrace covered with a thin mantle of alluvium on a ten-acre triangular plot between Soquel Creek and its tributary, Love Creek.

I stand in the searing heat

in my beat-up robe,

ready to fill the depleted feeders,

with bags of mealworm, millet,

black-oil seeds, and suet—

when I see it— big as a boot,

wings beating like a raptor—

as it drops to my dried-out garden,

scattering the chickadees and bushtits,

sending up a pulse of quail.

White crescent on her hind-neck

and a block of pink-checkered shine,

she turns her nape to the sun, shows

her dove-gray chest, palest rose

like dusty silk.

So like a passenger pigeon,

for a minute I think Miracle!

A Lazarus bird has returned.

Sixty years living here, I’ve never

seen this city-hater hazard flight

out of the buckeye poison and tick trees

where they gather and thrum,

weave sticks nesting single eggs,

the yolks scavenged by jays,

their hatchlings, murdered and switched

with changeling cowbirds.

Look what it’s come to—

kids grown, my father dead,

a mother too old to hate,

two husbands gone, memories

of a lover slivered in my gut

like shards I can’t work out.

Waiting for another clumsy visitor

from a place I thought was empty—

cousin to a glowing steel-grey ghost.

So fearful and so hungry.

© Dion O'Reilly

Dispatch from the West

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Summer 2023

It’s fire time again.

So far so good.

Fog in the mornings

Erases the trees.

Shafts of sunlight

Break up the mist,

All of it, the same.

All of it, waiting.

Nothing for my diary.

Just records broken

Far to the north—

A heat dome like a dome

Of silence, but no one’s

Getting smart.

I admit it, I’m terrified,

Terrified of the hungry air

Taking back the slugs,

Earth and sky making

God-love as my house collapses.

I stare out the window, a black cat

Likes my meadow, sits

On the sidelines. Watches

The quail tilt their nervous hats,

Whirl to the bosky creek.

Nothing’s forgiven. Nothing’s forgotten.

Not last winter’s rain, too soft

To snuff the smoldering roots.

Not the roll cloud’s belly,

Pricking snags into flame.

For now, let’s praise

The cold Pacific.

Still cold. Oh Lord, still cold.

It lays its mist hand on me.

Says Quiet. Quiet!

Stop it. Be still.

First published in Topical.

© Dion O'Reilly

Hunger Moon

February 9, 2020

by Dion O'Reilly

watches us fast while the world freezes,

while game is thin, and there’s nothing

to eat in the lingering winter

but a fatless rabbit and a dirty root.

Storm Moon, Snow Moon we say—

but this year, sun for weeks. Dry wind

downs a power line, sets a pine ablaze,

no rain, no cloak of morning frost,

no meadow grass bent beneath a crystal sheet.

But isn’t this a hunger? A desire for winter

so deep, my bones feel like dust, my gut

hollow, waiting for the rhythm of rainfall

swept from the windshield as I drive downtown

to buy Picuda oil, shade coffee, Chilean grapes.

Hunger Moon, I want it all—the tap on the flue,

the wood stove fueled by a wet-fallen oak,

the thrill moment of takeoff,

droplets on my window pushed back by a great force.

Even in summer, when the garden is a reckless mess

of cress and fat-bottom squash—

Hunger Moon, you follow me.

First published in Chautauqua.

© Dion O'Reilly

Musth

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Spring 2018

The word for when bull elephants are straight-up crazy

to smash, fuck and kill, their penises longer than

yardsticks, erect for months at a time, a stream of urine

dribbling a trail of stench, sludge of hormones

leaking from their temples and running into their mouths.

They tell the truth with trumpet, stomp, and stink. No

veneer

in the few wild islands of green that remain.

In zoos and on the streets of Burma, the spell lasts

only days because they’re chained, starved, held

in solitary. Weakening the body weakens

the frenzy. What else can be done? There’s no realm

vast enough for such delirium. I think of the rough

boys I grew up with, the ones who hunted and ate

squirrels, the flesh gamy and smelling of bay trees.

The barefoot trails my friends walked to the creek are gone,

and so are the steelhead, snagged on wormy hooks,

cooked in a blaze on the rocky floodplain.

Teddy Roosevelt said War is imperative upon honorable men,

hoping his sons returned with missing limbs.

Mohammed Ali, what would he have done without

his elegant power? Arjuna even. How to spread the holy

Word whispered to him by Krishna, if not by rendering

it in blood. How can the male sex give it up? Their smooth ivory

flashing in the savannah sun, the gore and puncture,

the strong semen sending exactly who they are

into this diminishing world.

© Dion O'Reilly

Plenty

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Summer 2023

August, the last of the apricots

haunts the trees. Their furred skins, split,

rotten and dangerous, crawling

with stingers on the unseen

side of the globes.

Above me, buzzards tilt in the heat.

Do they miss the condors?

The stiff keratin of the bigger beak

to splay a corpse’s flanks, break it

for a weaker brother.

I heard we once crept

behind hyenas, cracked

the bones of their leavings,

squatted and sucked the soft insides.

So many ghosts shimmer

the sky, shiver the leaves—

all the helpmates, swarms

of the world, whispering,

Let me feed my hunger first—

then you.

First published in Salamander.

© Dion O'Reilly

Rivervale

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Fall 2017

We slammed doors. We set out shoeless on trails of powdery sand,

turned a corner to the river, smelled pockets of cool air rank

with black mud. Maple trees leaned in, dropped leaves that rested

like bruised hands on the skin of the water, then floated away

around the high rocks at the bend. None of our mother’s bitched-out

tasks, no sudden hands of brothers slapped away. No pimped-out

sisters or fatherless boys. No pirate-eyed stepfathers drunk

in La-Z-Boys. Gone was the stench of spilled beer and rat turds.

We learned downstream. We learned leaving. We learned someday.

Herons lifted their great bodies from the sandy streambed, shining

fish caught in their tapered beaks and the agony

twisting in the air made sense. We looked to the world

beneath the clear surface with its teeming minnows, we pushed

shin-deep through the creek, crawdads hiding, black

pincers pointing out. We snatched living food from the river—

steelhead and trout. We drank the water.

© Dion O'Reilly

Talisman

based on consumer research conducted in Saigon

by the World Wildlife Fund.

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Fall 2023

The rhino horn razored into peels, beaten to a powder,

a tea brewed, a man sipping it for a night of pleasure,

or mixed with lime and spring water

for acne, crows’ feet, perhaps a tonic to sweep the sludge from a gallbladder—

That’s how I imagined it—the animal, shot, and while he struggled,

the spike cut with a power saw, wrapped in wax paper,

maybe bubble wrap, maybe thrown naked into a Range Rover,

carried across the bumpy savannah with more

of its kind on a good day for starving poachers,

then loaded into boats and taken to a city, where

it ends up in the backseat of a car—

A Tesla, maybe, because people who buy the horn

are health conscious and wealthy, with strong desires

to reaffirm their social status, buy gifts for

an unreachable lover, a would-be boss, or a son’s teacher

because the horn possesses enchantment—

it makes people like you, strengthens

the silky bonds among peers, so when one

receives such a present—well, they feel properly admired. Then

there are those who store it as talisman—

a piece of legendary head, a skewer to impale a lion,

flip it into African dust— more powerful than

a blue pill, a statue of Ganesh, a pair of petrochemical vegan

shoes. Better than the biker jacket I bought, fragrant

of leather, stripped

from the pink-fatted bodies of free-range cows.

First published: Agents of Change: Art & Poetry Project

© Dion O'Reilly

White Hawk

by Dion O'Reilly

The mourning doves cooed

their question—Where? Where?

but today, silence.

I filled the feeders

just after dawn, saw the patch

of fluffy down

on the grass below.

One wing feather with a black dot,

told me who died.

Probably a hawk—

my favorite white one,

the leucistic one—

plunged from the sky,

snatched up the dove

settled on the pine,

stood, gripping the blood-

pink neck, and shrieked

a call echoing

down the long valley.

That piebald raptor—

the one I’ve watched

for years, proud that she

chose to live above my field,

as if she were mine,

a totem, my emblem of grace,

the one who snatches me

out of my thoughts,

stuns me on mornings

when I wake, dull, frightened

by my own emptiness,

how sharp and thin

the edges I balance on.

I hear her

shrill and alone,

drifting on the warm thermals

like the outstretched palm of a ghost.

© Dion O'Reilly

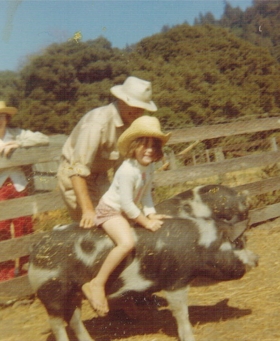

Why Did I Call my Pig?

by Dion O'Reilly

From Canary Fall 2020

I watched my mother call her,

I watched my sister too.

My father chased her.

They tried to round her up,

but my piebald oinker was quick,

her squeals greasing the air.

She knew the jig was up,

ran to the farthest corner, down

by the creek and the steep ravine,

hid in the shadows under oak trees,

rooting prickled leaves and acorns

with her wet ringed snout.

My huge baby, companion

on aimless teenage days

when I balanced on the fencepost, listening

to her belly-deep rumble,

scratched with a stick her itchy,

thick-skinned back.

It wasn’t for the sausage or ham,

the pork chops, or the slab kind

of bacon you couldn’t find in stores.

The butcher with a rifle,

stood impatient by his Chevy truck

its hook and chain ready

to haul the limp sow up,

to scrape the skin and slice the stomach

in a thin red line, the bowels spilling

glazy as moonstones.

Forgive me. To show off my small power,

I called her— the one she loved—

and she came running.

Previously published in the author's collection Ghost Dogs.

© Dion O'Reilly

Yellow

by Dion O'Reilly

It’s February, and the acacia

is blooming. Not wet,

though winter’s well along,

and the flowers by now

should be cold and sodden.

No matter. The air is helpless,

punch-drunk with pollen.

I know what’s next—

rooty mustard. Fields of it

mixed with the weightless

mouths of sour grass

showing their throats

as they shift on listless stems.

Yellow’s the first color of spring.

Hope yellow. Sick yellow.

Kitchen yellow. Pollen-petaled heart

of the columbine yellow, she-lost-

her-mind-and-ran-away-with-the-

pearl-handled-kitchen-knives yellow.

Head home to California

on the Gray Rabbit bus line,

from Seattle to San Francisco,

seats stripped-out, hippies

on dirty mattresses,

spooning and massaging

above the hum of the drivetrain.

Stop at Crescent City, stand

on a ridge, above a full-bloom meadow.

All that yellow

feeding my brain after nothing

but pine and pewter-grey.

I’m home. Thirty years now,

the rain behind me,

but I’m calling for it

down from the north

to scrub the thick air,

dampen the dried loam.

I’m too old to climb

the silver-skinned acacias,

botched with notches of crumbly black,

to sit thirty-feet-up

and scratch the bark’s thin skin,

smell the whiskey-wood stink,

see the hard green beneath,

smooth as muscle on an athlete’s arms.

To bower myself, safe

between limb and trunk

like I did when I was six

thinking nothing could touch me.

Not strange weather,

not whatever way the world ends.

Originally appeared in the author’s collection Ghost Dogs

© Dion O'Reilly