Issue Number 19, Winter 2012-13

Contents

- Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost

- Baylands Meditation

Dumbarton Bridge, Autumn 2011 by Al Young - Bear on I-40 by Karen Terrey

- Blueberry Ridge: A Poet Weighs In by Barbara Swift Brauer

- Broken by Gail Rudd Entrekin

- Communion by Doktor Bols

- Flee Qualicum Beach, BC by Catherine Owen

- Gone

The Common Swift: Apus apus by Peter Branson - Heartbeat of the World by Susan Dale

- Horned Rhino Population by Maya Khosla

- Letters from the Hinterland #3, New Year by Raymond Greiner

- Lost Hills by Judie Rae

- Rosary by Matthew Brown

- Shell Mudra by Roberta Feins

- The Condemned by Dan Howell

- Warrior Describes Men Wandering Around Alaska

Looking for a TV Set by Scott Starbuck - What, Where? by Juditha Dowd

- When Homer Roams by Cynthia Atkins

- Winter Cottonwood by Cara Chamberlain

- Winter Sugar by Dawn McGuire

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening

by Robert Frost

(1874-1963)

At the writing of this poem in 1923, Robert Frost lived on a farm in Derry, New Hampshire, in the Beaver Brook watershed near Pine Island Pond.

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

© Robert Frost

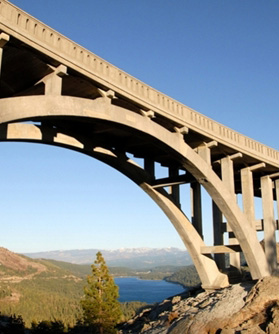

Baylands Meditation

Dumbarton Bridge, Autumn 2011

by Al Young

Native to Mississippi's Gulf Coast, Michigan emigré Al Young, a longtime California Peninsula resident, has lived in Berkeley since Y2K.

In one cinematic, galactic pull-back,

you finally get the raw hang of it,

you get it that sweat and pee and breath itself

evaporate. On down the line, we drink

all the water we make. No outside water

gets in, no ancient water gets out.

Breath by breath, spring by spring,

light-years at a time, everything alive leans

on every living presence. Feel this kiss

of cloud-fog and rain and stream and tide

and shore – soft, hard, fricative, alive

where feel and touch still taste and smell.

© Al Young

Bear on I-40

by Karen Terrey

Karen lives in Truckee, California, within sight of the Truckee River, part of the Lake Tahoe Watershed. The river runs about 120 miles from its source, Lake Tahoe, to its end in Pyramid Lake, just north of Fernley, Nevada.

A black bear hangs from arched girders

below the concrete bridge.

He knows green lichen, crashing water on

granite. He doesn’t know transparent webbing

stretched below. Men on ropes,

tied in to the bridge above, spin like spiders.

He doesn’t know physics of a net, security

of a line, skill of a knot.

Mostly, the bear knows silence,

involuntary breathing. His snout

scents humans cars buses roaring overhead.

When he leaped off the bridge

he twisted to cling a lip of structure

beneath, heavy body tightening.

After the swinging, tendons strained,

claws scraped. Now,

hanging.

Lake sources still hide beneath gauzy ice.

Manzanita branches red in the dusk. Slowly

he chins up the support,

black eyes blinking.

The fall is long. The net is strung.

His thick waiting a dark mountain at night.

He doesn’t know net.

© Karen Terrey

Blueberry Ridge: A Poet Weighs In

by Barbara Swift Brauer

Barbara lives in the Lagunitas Creek watershed in the San Geronimo Valley, the last un-dammed headwater tributary of Lagunitas Creek. Her home is within earshot of ephemeral and year-round creeks, just down the road from the fish ladder where coho salmon can be seen along their annual journey upstream to their spawning grounds.

Make no mistake

this hill is not dispensable.

What else to balance the gibbous moon,

the westering sun

on a fiery February day?

See how its slopes round with the purpose,

ravines run lush with it,

its roots of rock thrust deep.

Where else do we come for small miracles?

Two pines on a high ridge.

Make no mistake, this meeting

is the work of centuries:

the uplift of plates

and shifting surface,

mountain and coastal plain.

Advent of poppy, oak,

migration of grasses,

lizard and mammal.

Confluence of light.

And what you begin as a careless walk

becomes an intersection

of your life and all that greets you here.

From the Valley below drift truck rev,

door bang, car slam, dog bark and hammer.

Here, high amid bushes, crow hop,

flick of songbird, and the wide gaze of cows.

And this oak: ablaze with silence

in the still afternoon

saying nothing

saying everything.

© Barbara Swift Brauer

Broken

by Gail Rudd Entrekin

Gail lives amid the Coastal Range east of San Francisco Bay in the San Pablo Bay watershed just above San Pablo Creek on lands of the Chocheno and Karkin Ohlone people.

"Too many things are happening for even big hearts to hold."

– Anne Sexton

Broken hearts, broken bones, broken vows, promises, records,

broken noses, broken dreams, broken arrows, broken

bottles in the alley where the street guy throws his anger,

broken oil tank on the Valdez, broken wings, broken feathers,

black seas, rising seas, broken ice shelf, white bears falling

in the ocean, broken migration routes, swimming bears,

stranded elk, wrong side of the highway, wrong side

of the dam, broken salmon stair, broken fishermen,

dying towns, giving up, giving in, broken immune systems,

cancer cancer cancer, diabetes, new diseases, polyurethane

melting in the sun, give it to the kids to drink, microwave it

into broken eggs, fork them up, broken bird eggs

where the acid rain, broken atoms rushing fusion

reactions long tube blowing, broken watch

throw it in the basket, leave it

with the other trash, buy

another buy another

buy another –

© Gail Rudd Entrekin

Communion

by Doktor Bols

We eat this lamb

with rice and naan

and fragments of the bone

are in the curry

Imagine fractured collarbone

Imagine splinters in the steaming

pot of breath

and blood and punctured muscles rising

when something that once walked

this earth and lived

off this land and the oxygen

above it lies contorted,

tilted to the side that didn't

have its ribcage broken in

and cooked until the flesh

slides off the bone and is

so tender and it can't

say no or defend

itself.

© Doktor Bols

Flee Qualicum Beach, BC

by Catherine Owen

Catherine lives on the edge of the Lower Fraser Estuary where it runs into Vancouver, BC, down from Hope. She regularly walks the trails by the water where one can encounter otters, bald eagles, herons and the occasional coyote.

As if everything seeks to escape us – the young deer arcing in front of the bus, just

making it, dashing past side-of-the-highway bracken, its eyes full of why,

the stupid engines, its heart hurtling fear, then the darting heron who must wait, wait,

til the dumb bathers in Lycra, lithe-less teeming over the beach near evening,

only one more Seadoo trip, one more basky lassitude, but the heron needs to hunt, whippets

into the waves, eyes flickering between the retreating leaps of fish, diminished to minnow

& the chance of being chased by dog, child, a camera’s gawp over those “strange looking creatures

aren’t they, dear,” even the boy, two or three, hunkered down in the bushes & eel grass

by the side of the boardwalk, naked, taking a sweet shit, looks sideways, eyes a dark flit, terrified

lest his wildness be ceased as it will be & indoors with him & wrenched away, stuffed, extinct.

© Catherine Owen

Gone

The Common Swift: Apus apus

by Peter Branson

Peter lives in the shadow of Mow Cop and Congleton Edge to the east, overlooking the Cheshire Plain westward, between the watersheds of Trent, Mersey and Dee.

Not here this year, lost souls, homes worn away,

handhold to fingertips, like spent pueblos.

They don’t die back or hibernate, but cruise

vast distances above the turning world.

July evenings, they side-step, scissor-kick

thin air, etch pen ‘n’ ink invisible

tattoos. Banshees, dust devils in wet suits,

anchors on skeins of rising light, they’re soon

shrill specks in your mind’s eye. Time lords, stealth craft

hot wired to while away brief summer nights,

they preen, breed on the wing, use what the wind

blows in to feed, fix nests under house eaves.

Broadcast, they silhouette the urban sky,

shape-shift, in one heartbeat, present and past.

© Peter Branson

Heartbeat of the World

by Susan Dale

Susan lives on a farm in Ohio near Lake Erie in the Mills Creek/Pipe Creek watershed, amongst her many gardens, the forest and fields.

Within a sleep

of the universal dream

dreaming me

I lean out in the darkness

to hear a heartbeat of the world

Listening wide

straining with sinew and soul

I hear flapping wings

Ah, it is the bird of scripture

The Vikings buried him

Remember, with your being,

he under layers of Arctic ice

Prophesy decreed

that a shrill brass sun

melt and free his wings

to thrash the skies to raw skin winds

Winds to push across

skies, deeply moving

Winds to push clouds

to gallop through the heavens

Wings talk around winds

But what words tell of winds

gasping with the sounds of dead things washing on shore

Ashes - bones

arteries clogged with oil

Oil - the black blood of our destruction

And in the air, a heavy scent of gone

West winds blow vapors cold on leaves, quivering

on trees with thin chests

and branches reach out in search of embrace

Oh, tired earth of heavy-lidded eyes

dusty clouds - weeping waters

of voices deafened by silence

Our words spoken with fingers

forming the telling

of living to die

existing to endure

We have filled

to fall out of ourselves

and so must we swim to the moon

But what will light our way?

Our shadows lengthening and widening

darken the moon

Souls of stars lie bare

The black V of wings beat the sun to shreds

Winds dip and roar

Yet stir up only pale raindrops

In this hollow rain

stands a girl with broken umbrella

She’s trading her memories

for a withered apple in a faded pocket

Her brother sells his poems

a penny apiece

All begin with the line …

life yearns to live

And end …

life is longing for itself

© Susan Dale

Horned Rhino Population

by Maya Khosla

Maya lives near Copeland Creek, which is a part of the Russian River watershed in Sonoma County.

You could die when it’s time. Or for the “medicine” in the meat of your keratin. Many among you once strayed too far on the opposite side, the river muscling through your floodplain. Only horns were sliced off. The rest, flesh, hooves, skin-shields, sank into sun. Scents of skull and ribcage drew civets, fishing cats. Remains passed unannounced to the larger family—vulture, hyena, fungus. Receded to hints of bone. Wind wiped the crumpled water, emerged as an incantation tinctured with cartilage. Now glassy plates of water slip and buckle. The crowns of two trees stretch closer, touch above the point where one of you gave birth. Forks of purpled light rise and flash before slipping from the sky like nameless fish. Shuddering the flies off, you who remain are so blended

with mud and silt, you

are almost absent.

© Maya Khosla

Letters from the Hinterland #3, New Year

by Raymond Greiner

Raymond lives with his canine companions Orion and Venus on 14 acres of remote forested and pasture land about three miles from the hamlet of Paragon, Indiana, in a cabin about 500 yards from the little-traveled road.

What is predictable? We will experience the repetitive cycle of weather patterns. Spring storms will come. Earthquakes, floods and hurricanes, these are certainties and have been active as a form of Earth's energy release since its inception. Cultural changes are also a certainty, but less predictable in detail, as the "end of the world" prophets pop up regularly. Of course the world will eventually end, but as things are now, it appears to be a ways off.

As we pivot into this ambiguous, new span of time and dimension our individual agendas are aligning within our thoughts, much to do with stage of life, or a particular position we have achieved in the previous year. Opportunities will appear, some will direct us forward, others may fizzle, losing value quickly. The heavy substance users will think deeply about moving away from their substance of choice, obese people will think about how much better their lives would be if they allowed their bodies to wander back to the way they were at one time. Many good thoughts emerge as each new year enters our lives.

Beyond the traditional resolutions and predictions, the most profound issue is hope. Hope for life's functions to discover better paths leading to more harmonious fulfillment. Technological advancements are driving forward at quantum speeds, inundating us with changes coming so quickly assimilation becomes a challenge. I don't see this slowing down in the future; therefore, gauging usefulness and choices is the highest priority. There is also a movement toward allowing deeper spiritual enlightenment to flow. Growing inwardly is likely the key to fusing cultural direction with technology in a positive manner. Almost all spiritual paths lead to betterment regarding personal inner growth.

My particular sanctuary is nature and its abundant revelations regarding the purpose of life and how it blends with the Earth, an adjusting momentum, conquering challenges through evolutionary processes. As we address human-born challenges, it is to our advantage to emulate nature and adjust, evolve, striding with confidence in a cadence of concord. The ancients were bound to spiritual connection. It stabilized them, creating unity. It is a hope that in this contemporary, historical time we can realize the values in this important aspiration.

It was joyful yesterday to have that snowfall. It was a wet snow, clinging to the trees, so beautiful. Canine pals Orion and Venus sensed this and ran in a big circle. Orion bites the snow, and Venus watches him, a bit puzzled as to why he is doing that. The trees are barren but the clinging snow seems to highlight them, even without their leaves. My dogs adjust to things; whatever the circumstances, they adjust. I try to learn this from them.

From the hinterland.

© Raymond Greiner

Lost Hills

by Judie Rae

Judie, a Canadian, lives in Nevada City, California, in the South Yuba Watershed, an area whose trees and waterways remind her of magical summers spent at her grandmother’s cottage on the Ottawa River.

Meet me at the dump, he said,

the words of a practical man.

And so she trailered him there

long in tooth, foundered,

to his final destiny among

the rusted Frigidaires, bald

tires, mounds

of diapers and orange rinds.

Seagulls and turkey

vultures

looked on while

the vet, a practical man,

searched for vein

in thickened neck, thrust

needle through the aged,

rough coat.

When he was down

still she spoke to him

murmured of hills, enchanted

light and fields

gold with summer wheat.

His hooves pawed

a final time

at the earth

bare of sage, chaparral,

but perhaps

he remembered.

The stench of fermented waste,

like fog,

hung

in arid heat.

Decay, a fact.

Love, an old beast

gracious

in this last act

forgiving

Previously published in Nimord 2008.

© Judie Rae

Rosary

by Matthew Brown

Matthew grew up on the Ozark bluffs that outline the central edge of the American Bottoms, a glacially carved valley split by the Mississippi river between its confluences with the Missouri and the Ohio.

Queen Anne’s Lace along the road side,

becoming asphalt.

Poison ivy swallowing split trunks of second growth elm.

Boys in denim pulling weeds in parking lots painted

with straight lines.

Standing by the Mississippi in winter on the island left by a three hundred year flood, fits of light come through the seasonally dead branches of living trees pouring out evenly across riveted tracks left by the few farmers who have stayed to plant, exactly as they should. The smoke tilled channels of barges churn out shallow eddied depressions mainly down river with loads of split grain and crushed limestone, pushing segmented waves of mud bottomed water across the short sand bars over the wheel tracks where the old city used to be.

Yard dogs carving out the chain-length half-moons

of runs.

Colored folk humming on porches.

Small water rubbing over stripped and smoothing creek stones.

Box turtles turned over in the sun.

The people who came here with the first of us, down from the north, who called themselves the perfect people, as opposed to the Iroquois who, armed with guns and steel traded with the Dutch and then the English for furs and land already for a hundred years at least, had stolen their land in the prairies. The perfect people, the Illini confederation, who the French called Les Illinois, had, in their Algonquin tongue, over twenty names for the river that they settled and the land around it. Most of them began with a term of endearment, father– Father of waters, Father of a thousand cities.

Lines between poles for hanging laundry.

Split rails from our land to theirs.

Gravestones moved above the bluffs.

Boxes filled with empty bones.

It could be any of these, apple holes at Christmas, the stone foundation for a dry well below the springlot, barn swallows in the henhouse. When my grandfather came back from the service, like everyone else here, he raised livestock, and planted crops to feed them. During the last war, American chemical companies had come up with herbicides to clear out the dense tropic growth of the Pacific islands so that enemy troops could be observed and bombed by planes. They also developed pesticides to eradicate disease carrying insects that were killing GI’s; malaria ridden mosquitos. Agricultural companies, such as Monsanto, based out of St. Louis, led the way in such innovations, and after the war they altered and marketed these sprays, Dichloro-Diphenyl- Trichlorethane, or DDT, to farmers as the way to lose less and earn more per acre.

Twilight quiet in the north pond.

Names notched in sows’ ears.

No more than forty lashes,

laid well on.

The sneed of a scythe, sickle blades, a rusted bundle of bale ties, hot-long days

in the hayfield.

Fifth-legged frogs awake in the crick.

DDT was outlawed in the United States in 1972 after it was leaked that side effects often included highly lethal forms of kidney and liver cancers. During the Vietnam Conflict, Monsanto became the leading producer of Agent Orange. In 2002 Vietnam requested international assistance in order to address scores of thousands of birth defects connected to American attempts at deforestation. Monsanto maintains claims that the herbicide cannot be linked to any specific illnesses and has evaded any serious legal call for reparations. As of 2008, the company holds contracts worth over one billion dollars to provide the US government with defoliating herbicides set to be sprayed indiscriminately over tracts of Colombian agricultural sectors in order to fight narcotics producers. Regional agricultural organizations have claimed widespread contaminations of water sources and crops in rural villages where families can no longer grow staple food supplies or access clean water sources.

Bales of bolls about the gin.

Tree stands in summer.

Salt licks by the stairwell.

There are mouths that say things we can’t say

or don’t.

There are mouths that take them back.

At sixty four, my grandfather died, his body riddled with tumors, spread from the kidneys. The farm, granted to his ancestors for service in conquering the West during the revolution, has become little more than a hobby for his daughters and their families. Led by the marketing of GMO’s by major agribusiness, along with global stranglehold on world food commodity prices held by the World Bank and the WTO, less than one percent of food stuffs in the United States are grown on small scale family farms.

Hay rakes in the field at dawn.

A man smoking long cigarettes in an open door.

It could be any of these things, opened up. In the summer, nitrogen levels from herb and pesticides used by farmers flowing from the Mississippi delta, which releases forty percent of America’s fresh water into the ocean, create a dead zone larger than the state of New Jersey, devoid of enough oxygen to sustain any form of life. In the Indian Warangal District of Andhra Pradesh, local small scale independent cotton farmers, cultivating sometimes half to one whole acre of land apiece, have been convinced by outside money lenders to buy Monsanto’s genetically enhanced Bollgard cotton, promised to double yields and resist pests. The farmers go into debt to buy the seeds, then more debt to buy the fertilizers needed to produce the desired results, then still more debt to irrigate the extra water needed by the hybrid plants.

Hollyhocks on the table in a bowl.

Broken light bulbs on the doorstep.

Sweat beads on a glass of ice.

Small women eating clean fruit from the cupboard.

To date, hundreds of Indian farmers in Andhra Pradesh have taken their own lives by drinking pesticides to escape the guilt of losing family land holdings and to deliver their families from debt. The Indian government has a policy of paying the families of farmers who have committed suicide about two thousand dollars to help settle accounts. Farmers choose this method, which takes a minimum of several excruciating hours to slowly shut down the central nervous system, so that their deaths cannot possibly be written off as an accident.

Fat snakes split by tires on the roadsides.

Honeysuckle blossoms in March.

Fresh water run too rich to grow air.

© Matthew Brown

Shell Mudra

by Roberta Feins

Roberta Feins lives in Seattle in the Piper's Creek Watershed. From her writing desk she can see a forest of big-leaf maples and conifers, Puget Sound, and the Olympic Mountains.

Their names replay Homer:

Cyclops, Stentor, Nereis,

joined to the names of scientists:

jensenii, darwinii, hutchinsoniana.

Tide by tide, we wade deeper in a fetish of destruction,

Thanatos is in our crooked defended marrow.

With curved fingers, I trace their scalloped

ridges: cockles, clams, coquina.

Eternal, veiled and nacred,

their living flesh will die and die again

and on this tumbled beach, pile into heaps

and mounds, press slowly into continents.

Amphitrite, Cassandra, Megalops

will siren, long after their names are lost,

long after we slice open

the clenched muscle of our ferocious history.

Originally published in Switched-on Gutenberg, the poem is part of a larger work, "Hunger on Marco Island."

© Roberta Feins

The Condemned

by Dan Howell

Dan lives in the Town Branch watershed in the Heart of the Bluegrass in the commonwealth of Kentucky, which has more miles of running water than any state other than Alaska.

How painful to think that the cheetah could disappear forever

by the next generation the pretty seahorse and maybe the honeybee

elm and oak and painful to know what’s missing already a million

passenger pigeons in a single flock a flying island miles of buffalo

acres of elephants iridescent dolphins in shoals in the old Aegean

and soon we can say just name something else going or dead and gone

graceful or not “useful”or not creature forest desert prairie river ocean

air Yes we’re all stupid and gifted and vicious and kind and finally

condemned when driven to do far too much with the world or to it

while typically we learn barely enough to start mourning

© Dan Howell

Warrior Describes Men Wandering Around Alaska

Looking for a TV Set

by Scott Starbuck

Scott travels between the north Oregon Coast, Columbia River Gorge, and his teaching job overlooking The Rose Creek Watershed in California.

"What you got here?"

the newcomers demand,

tired and angry,

unplanned landing.

The Old One smiles again.

He says ----

we got plenty of fish

and plenty of friends.

He says ---- Look

by the river.

We have the raven.

The spruce. The moon.

Sea is quiet.

Stay if you wish

and tell us

what you got.

Previously published in The Lucid Stone and The Warrior Poems (poetry chapbook) by Pudding House.

© Scott Starbuck

What, Where?

by Juditha Dowd

Juditha lives in Delaware Township, New Jersey, near the river of the same name in the Middle Delaware-Musconetcong watershed.

Audubon toted paper for his drawings,

tools and preservatives to keep the skins.

He posed his endless questions to the earth—

estuary’s muck and distant mountain—

where he’d daily wander fifty miles or more

in moccasins, his gun across his shoulder.

Today we run our marathons in spandex,

our shoes are the handiwork of engineers,

and the remnant wilderness is wholly owned.

Gone, the profusion that lit his waking dreams:

Forty beavers glistening in their winter coats,

the sandhill cranes a river in the sky.

© Juditha Dowd

When Homer Roams

by Cynthia Atkins

Cynthia and Homer live on the Maury River and their watershed is the Chesapeake Bay by way of the James River.

It’s pointless calling, my thin voice

caught like gossip gone missing

from the laundry-line of home.

I’m in no position

to give advice—You have all the knowing

ahead of me. Ears tipped into a tarot card

of portents—Oracle of scent and ethos—

drawn to the outskirts of puddle, leaf,

carcass, anything decayed, snowflake.

This is your work,

it’s serious business! With every breath,

willing to face death. You hear the sounds,

the vibrations once removed from

where I am not—like just missing

the bus from the bus stop.

You’ll wait for the kill,

steady, patient as a slow drip

in the well. That carefully made

lining and rill of your jowl flutters

with the nuance of butterfly wings.

The extra flap of skin always expecting

company—the way we keep

a roll-out sofa for guests. Excuse us our

patio furniture, safe anchors—the area rugs

where you’ve kept vigil, hold the habits

of our remorse. We know how to hold

a camera, we know how to visit

the sick with soup and gifts.

We’re only human.

Dog of the hearth. Wolf of the wild.

That long yowl is an anthem

unto itself. Stretched out, a rambling train

after the rains. Short days to night.

My voice calling, beyond the doormat,

the smoke-plumed town, where the lights

are shutting down, and your prints

pander to us—we have no clue.

Phantom warrior showing us

how to bring the words

back to their bones.

Previously published in the Hawaii Review.

© Cynthia Atkins

Winter Cottonwood

by Cara Chamberlain

Cara lives below the sandstone rim rock that lines the Yellowstone River Valley and gives America's longest undammed body of water its widely used name. In Apsáalooke (the Crow Indian language), however, it is called Elk River.

How could they

not hurt,

those wind-chipped

branches,

twigs and leaves

ant-mined

birdfoot-

scarified,

hopeful at minus

twenty

with buds

held ready

for summer and again

an early fall

when leaves

jangle like twice-bit

coins, those

forgeries.

Essential

five main branches

climb toward

a blue so pale

it might not exist

but for some

persistence

unknown. The course

is to imagine it all

at rest, the sap reduced

to icy blood

so stopped it can

rise on frozen dust

or go down through

puzzling turns,

an axis of hurt

and hardness

to make my coming

death part of the world.

© Cara Chamberlain

Winter Sugar

by Dawn McGuire

Dawn lives by a tiny riparian habitat in the Orinda Woods in Northern Calfiornia. She shares the land with a splendid gray fox who hunts there. Orinda was named in honor of Katherine Philips, the first woman in England to be acclaimed as a poet in her own lifetime: "the Matchless Orinda" (1632-1664).

for Monica Tranströmer

In November, the Northern Spring

Peeper (P. crucifer) turns to ice.

The kidneys in their tiny tunics

freeze; the liver in its capsule,

spleen in its sac, refrigerate.

The brain is a milligram of iceberg

in a helmet.

With the ears’ oval windows

frosted over, nothing sings,

but sleeps, hard as granite candy,

under litter leaf.

This far north of song,

the silence could be endless.

Ocean’s last lid.

But in the depths, where life

keeps its best silver, the cells

are filled with fluent waters.

A few extra molecules of sugar

become winter antifreeze. No ice

spikes form, no inner membranes

break, no essentials leak.

When the sun’s elliptic fire

crosses north again, the mute brown

shuck begins to thaw. The curious

X on its back for which it is named

no one explains,

but the heart’s three chambers start

to beat, and the brain’s dopamine

as always, promises a kiss.

So it begins,

the boreal chorus. Sweet-kept

and built loud; built to deafen

even death.

© Dawn McGuire