Issue Number 23, Winter 2013-14

Contents

- Armageddon Zen by Lori Lamothe

- Carp by Christine Butterworth-McDermott

- Chilcotin Wild Horses by Daniel MacIsaac

- Fencebreaker Creek by Taylor Graham

- Great-grandmother Explains Global Warming by Judy Brackett

- In Memory of Wolf Number 832F by Diane Lechleitner

- Leaving the Aldo Leopold Wilderness by Timothy Staley

- Lecture on Coral Reefs by Holly J. Hughes

- Letters from the Hinterland #7, Habitation by Raymond Greiner

- Lonesome George: the last member of the Chelonoidis abingdoni species (circa 1912- 2012) by Sarah Giragosian

- Lynx by David Chorlton

- Shale by Kelsey Sather

- Shearon Harris Nuclear Power Plant by Kelly Jones

- The Extinction Stories: The Labrador Duck by Daniel Hudon

- The Furnace by Patti Capel Swartz

- The Lake in Winter by Jerry Dennis

- The Wintering Birds by James Eret

- Where the Radiation Goes by Lucille Lang Day

- The Inspired Pen of a Wildlife Warrior by Barbara Lee

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

Armageddon Zen

by Lori Lamothe

Lori lives with her daughter and Siberian husky in a cottage on two acres of land in the Nashua River Watershed. She remembers her grandmother telling her stories about the Nashua changing color when the factories along the river dumped dyes into the water. At one point the river was so polluted its chief life form was sewage worms. Thanks to the efforts of environmental groups it now "runs clean."

The only station the roof will play is static.

The air colorless. The day colorless.

The threat level is orange.

Last month constellations of snow fell through the dark.

The tree in the yard opened its palm for me

but I couldn’t see the future.

Be informed. Make a plan. Buy a kit.

Instead I watched silence fold sound into its black coat.

Indicators of such an attack may include

droplets of oily film on surfaces

The snowflakes lit memory.

I set one inside a lantern and entered a room.

inconsistent patterns of illness

unusual dead or dying animals

The world melted on my tongue.

© Lori Lamothe

Carp

by Christine Butterworth-McDermott

Christine resides in the piney woods of East Texas where flocks of grackles occasionally touch down.

Lotus seeds may remain viable

for as long as thirteen thousand years.

Roots to the bottom, the lotus sprouts

out of river soil to break the surface,

to spring pink into the air.

I swim in the muddy water of dark

attachment, pools of want and need.

The lotus unfolds its petals,

the expanding soul flowers.

I circle and circle the stalk

that leads to heaven, stir

the sludge of water. I cannot

tell what will sink and what

will rise from the murk.

I do not have that kind of time.

© Christine Butterworth-McDermott

Chilcotin Wild Horses

by Daniel MacIsaac

Dan lives and writes in a home overlooking Witty's Lagoon on Vancouver Island.

They died off

in the last Ice Age.

And for a century

of centuries

only the wild grass

remembered.

Broomtails blunt-toothed

and rough-hoofed,

a cayuse herd

stole back, cross-bred

from buffalo runners

and a claim-jumper’s plug.

Native flesh, foaled

from lean Andalusians

shipwrecked in America,

and drawn north

across sierra spine

and salt lake.

Now from pine scrub

to parched grassland,

the free herd thunders,

hides scarred

by snag and thorn,

not spurs.

Hoof beats echo,

rattling in

the dead throat

of a volcano,

ringing in

a vast crevasse.

Scoured again

by colossal ice

or scorched by

seismic fire,

the Chilcotin

turns barren.

Wild planets

wheel, gyre,

stampede --

first horses

again on that plain

of hurtling starlight.

© Daniel MacIsaac

Fencebreaker Creek

by Taylor Graham

After 24 years between forks of the Cosumnes, Taylor now lives among tributaries of the American River.

Yesterday afternoon, a blizzard of blue-

oak leaves covered the newly-swept deck.

By nightfall the rain gauge measured

2.5 inches. Just the beginning.

All night I dreamed storm. The rains

kept falling. Our seasonal creek - dry

most of the year - came to life, an animal

gorged on plastic bottles and tires

from upstream, tree-limbs that ripped out

our fence-crossing in its path.

The creek bucked like a mud-bay

bronco, down the bedrock staircases

off Stone Mountain. The hillsides

rode washing downstream.

For years we've lived here by grace

of title proved by plat and survey

pins driven into good soil.

I dreamed our little house held - a roof

perched like a nest atop rockpile,

pinnacle not yet eroded away.

I woke to calm before dawn, break

between storms. The news predicts 20

inches. What have we done to our

weather? This beautiful, dark morning.

© Taylor Graham

Great-grandmother Explains Global Warming

by Judy Brackett

Judy lives in the northern Sierra Nevada foothills just uphill from Deer Creek and minutes away from the South Yuba River.

One autumn the leaves did not fall—

not linden, not maple, not aspen, not oak—

turned crimson, turned pumpkin, turned daffodil

yellow but clung to their trees, perplexing

the squirrels, the deer, and the grownups.

As the air buzzed electric with wonder, with worry,

with nature gone haywire, great cosmic malfunction—

starbits pinging on rooftops and glittering the village,

and cloudsnippets, leafsize, swirling to earth

like heaven’s own feather beds split, and children swam

through the down and raked mammoth piles, tunneling

and jumping and sneezing.

While grownups wrung hands and called meetings,

climbed ladders, wrote letters, scraped bark,

and scanned the strange skies,

their children romped in the star chips, littering light,

then snuggled in beds, cloudfluff in their hair,

starshine on their pillows. On the night

of the solstice, full winter came on—hail and rain,

gray-blanket skies, snow and ice-sequined trees,

warm hues of the leaves bleeding through,

and everyone waited for springtime, half dream

and half dread, praying for green, for stars

in the heavens, for all’s right with the world.

© Judy Brackett

In Memory of Wolf Number 832F

by Diane Lechleitner

Diane lives on the east shore of the Hudson River across the river from Hook Mountain and, to the north, Haverstraw Bay. During winter eagles fish from ice floes, and in summer herons roost in a nearby tidal wetland.

She sniffed for mice in April meadows

and loped through groves of aspen,

chasing elk into the trees

on the other side of Soda Butte Creek.

When winter forced the herds

to lower ground

she followed their scent across frozen lakes,

in the rugged shadows

of the Absaroka Mountains,

turning in circles on icy nights

to burrow in the snow.

And when she covered her last distance,

east, to the Clark’s Fork Drainage,

she may have quickened her pace

at the vague whiff of men

and sound of snapping twigs,

moments before the wind blew gunsmoke.

© Diane Lechleitner

Leaving the Aldo Leopold Wilderness

by Timothy Staley

Tim lives along the Rio Grande where it cuts through the Mesilla Valley below the Organ Mountains deep in the Chihuahuan Desert.

After nine nimble days

in statuesque snow

I turn my dog and I

home. He splashes

on vivid red paws

across the Mimbres

and up the canyon.

I’m calmed by the

one-sided challenge of

the climb, with a sixty

pound pack I’m

floored by momentum.

From the mountain

I emerge again reset,

my strata of concerns

rolled back to tranquil.

If my truck had started

and lumbered us down

the forest road

High Lonesome Radio

could have come in

fuzzy at first, Christmas

a day away, bombs

going off in mosques,

and Condoleezza could say

something, but it doesn’t start

and we’re put to sleep

as snow darkens

the windshield.

© Timothy Staley

Lecture on Coral Reefs

by Holly J. Hughes

Holly is happy to have landed in the Chimacum River watershed at the foot of the Olympic Mountains on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington. For the last 30 years, she has spent part of each summer working on boats in the waters of the Alexander Archipelago of Southeast Alaska.

Tonight the scientist said, almost under his breath,

we are changing the ocean too fast for it to recover,

clicked to his next slide, his graph predicting

when the corals reefs will all be bleached:

one degree warmer, already the sea more acidic,

even with the melt from polar icecaps.

We squint as the line climbs the stairs,

then shoots straight up at 2020, ten years away

when the coral reefs will fade to gray

like the TV test pattern we watched as kids.

No yellow tangs hiding in crevices;

no blue parrotfish swaying in the surge.

We fall silent, stare as though it is a quiz

and we still can’t believe we could fail.

© Holly J. Hughes

Letters from the Hinterland #7, Habitation

by Raymond Greiner

Raymond lives with his canine companions Orion and Venus on 14 acres of remote forested and pasture land about three miles from the hamlet of Paragon, Indiana, in a cabin about 500 yards from the little-traveled road.

Home is a place of comfort and safety, shelter from the storm, a place for rest from daily toils and for planning tomorrow. Historically homes vary, ranging in scope and dimension from Buckingham Palace to cardboard shanties in third world countries, and every imaginable variation in between. Some folks have no home of permanence; wander city streets, sleeping under bridges or in other modest shelters. Some homes are constructed behind walls which serve as barriers from intrusion. Woods surrounded Thoreau’s cabin, built near Walden Pond, one room, with a fireplace, bed, table and three chairs. Each chair was given a name: Solitude, Friendship and Society. Thoreau’s notion was that a home should be small, offer warmth and comfort but not extravagance, forming a pathway to achieve higher consciousness and embrace frugality and simplicity as directive forces. In this modern era homes are reflections of identity and status, moving beyond basic shelters and becoming means for social expression, displaying positions of prominence and financial achievement. Where and how you live, the size and perceived value of your home, establishes social foundation and acceptance. Vanity is a large presence in home choices.

Baffin Island is a barren, arctic island, made up largely of granite rock and boulders; the flora is arctic grasses and moss. Wolves have lived and thrived on Baffin Island for thousands of years, feeding on arctic hares, lemmings and other small game. These wolves, classified as arctic wolves as compared to the more southerly grey wolf, do not hunt in packs, but often male and female will hunt as a team. One of the most interesting features of arctic wolf life is their dens, established in well-protected boulder crevices. The dens recycle to the next generation, using the same pathways for exit and entering. These solid granite pathways have grooves worn in them, worn from the soft pad of wolves’ paws over a long span of time, giving perspective on the longevity of these family dwellings. These dens are the wolves’ home, their place of safety, a place of welcome. Wolves have no vanity; they have society and order but place no value on the superficial.

My home is in a remote and beautiful place, surrounded by nature and quiet, and over the past 10 years I have had the opportunity to observe a variety of animals and their home choices. I have five bluebird boxes mounted at various places on the property, and I marvel at how birds and animals construct and occupy homes they design and build themselves.

One day I discovered an abandoned sparrow’s nest lying on the ground. It was so perfect; much of its construction material consisted of horsehair, lost when the local horses had brushed their tails on fence posts, barn posts, and other obstacles. I was amazed at how precisely these small hairs were woven in a perfect circle to create this nest, a task that would have been a daunting challenge for human hands.

Other nests abound. High in the oak and hickory trees are squirrels’ nests lined with duck feathers and other insulating materials. The hornets’ nest is a real engineering feat, firmly attached to a lower branch of a sturdy tree, standing up to nature’s wrath. Once while hiking the property trail in early spring, the ground covered with a light snow, I came upon a significant pile of fresh woodchips. Looking up about 30 feet on a basswood tree, I saw a perfectly symmetrical hole on the lee side of prevailing winds and storms, the work of a pileated woodpecker. The bird knew his/her wood and had built a home high and safe, selecting a tree that is the carver’s choice.

An opossum has a den in the hay barn, accesses its home via a space that tunnels the barn wall. I see it often in the late afternoon, leaving home to scavenge for food. Opossums are pre-historic, living fossils, dating back 60 million years, and they are among my favorite critters. True survivors. The dinosaur perished but the opossum prevailed.

I have been studying the history of the Adena people, who occupied a large portion of what is now South-Central Ohio. Further evidence of their lives has been found in West Virginia and parts of Indiana, along the Ohio River. The Adena lived from 1000-200 BCE, and anthropologists speculate that they represent the foundation culture that ultimately evolved into various Native American tribes. The Adena formed villages with unique small houses built from upright poles: round structures, covered with skins or bark, very sturdy homes. The Adena were also mound builders and artisans. Carved figures have been discovered on rocks, petroglyphs depicting their life activities and beliefs. The Adena were directly attached to the earth, forming cohesiveness with nature. Their homes were functional and simple, the very opposite of contemporary munuments to separation. Thoreau would have aligned with the Adena.

The film and television producer Aaron Spelling desired to build the largest home possible as a manner of identifying his success. He had had a terrible childhood, was horribly abused and bullied at school, causing him to be bedridden from injuries for long durations. He became a reader, escalating his mind to a higher dimension than those who had bullied him. This early life experience may have planted a seed, manifesting a desire to display his achievements later in life.

This mansion is huge, sprawling and simply staggering in dimension. Mansions are great sources for segregation, putting oneself on a pedestal, eliciting awe, and seeking social respect and identity. This desire is quite ingrained into the present day glut-oriented culture. The Adena were communal; housing was uniform and without social distinction. People functioned within the confines of unity, transiting life in tribal harmony. In our present day world when the rich and famous become rich and famous, their first reaction to their success is to build a mansion, segregate themselves from others, become overlords, indulging in excess. It would seem difficult to acquire a deep affection for a home that is measured in acres, as opposed to a smaller, more intimate space.

In Los Angeles there are 90,000 homeless people, and then there are the mansions. Spelling’s home is valued at 150 million dollars. I suspect that the Adena knew something that we still haven’t come to understand.

© Raymond Greiner

Lonesome George: the last member of the Chelonoidis abingdoni species (circa 1912- 2012)

by Sarah Giragosian

Sarah lives near the west banks of the Hudson River near the Albany Pine Bush, the only considerable pine barrens dune ecosystem in the US. Although a preserve was established in 1988, the pine bush has shrunk from 25,000 acres to 6,000 acres due to development in recent years.

Probably the God of Tortoises,

with his bacteria-rich kiss

and his shell as wide as a barouche,

loves you, George.

He will be magisterial but clement,

welcoming; he will scoop his neck

across the vault of heaven and take you in,

his ponderous face upon yours.

He will jest with you,

take you for a lope across the shaded lawns.

Light will play on the intricate scutes

of his shell when he reminds you

that no animal goes unmolested on this earth,

and to be the last is to suffer idolatry

or worse, this mortal irony:

the zoo plans to embalm you

(because preservation, though tardy

at this juncture in your lineage,

is pressing for posterity’s sake).

Someone will suture you,

mammoth and sloe-eyed, with dust deep

in the crevices of your skin,

and the ancient minerals of the earth,

for the last time, cemented in.

© Sarah Giragosian

Lynx

by David Chorlton

David lives close to the Sonoran Desert in central Phoenix in the Lower Salt Watershed, at an elevation of 1,124 feet with an average annual rainfall of 7.7 inches.

A cat with one paw in the night

moves slowly on a dirt path

where the sun expires

into a cool skin of light

left behind with each step.

He alone sees what he sees

and he is alone

where the ground gives beneath

his easy weight. His sudden face

parts grasses and his feet

soften stone when he stands

looking down at his reflection

in shallow water pooled

in a hollow. He can move

as fast as a guess disappearing

in trees, or be frozen so still

that his heart stalls

while the blood beneath his fur

keeps flowing. There he goes,

down a path into a thicket, with a spine

that dips between his shoulders

and his tail, and a flowing stride

that hides the tension

in his web of nerves.

© David Chorlton

Shale

by Kelsey Sather

Kelsey was born and raised on the northern periphery of the Gallatin Mountains in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. She spent the last couple of years studying Environmental Humanities where the Salt Lake Valley rises into the Wasatch Range.

Why Shale tried to cross the interstate I do not know, as there are mysteries creating voids between one species and another. Leashes were for pets, not companions, and Shale was a loyal friend. If nothing else, I held my skills as a dog owner above any natural inclinations—including the allure of road kill. It was maybe our twelfth time rock climbing at the Bozeman Pass in southwest Montana. Shale knew the drill: sniff around then hunker down while we scaled the limestone wall. This day, this day was different. Driving there I felt heavy with dread but dismissed the apprehension to a sky threatening rain yet again.

It was a slow-coming summer defined by overflowing riverbanks. Freak thunderstorms rolled into the Gallatin Valley every afternoon, carrying softball sized hail that totaled cars and broke all west-facing windows in Bozeman. A tornado even touched ground that same month two hours away in Billings, tearing an indoor stadium right out of the arid Montana soil. It was the second recorded tornado in Billings’ history, with the first being exactly 52 years prior to Shale’s death.

I found her on the dotted white line, maybe a minute too late, and knew she lay there dead. I carried her carcass, still warm, still fully intact, yet limp and unmoving, off the pavement and into the tall grass. I ran around screaming, pulling my hair in fistfuls and rambling about taking her to the vet. Exhausted, I sprawled out in the grass next to her and allowed the absolute of death to silence me with grief foreign in its suffocating grasp.

*

A tornado is the violent intercourse of heaven and earth manifest in spinning, reckless columns of air. Landspout, multiple vortexes, waterspout, gustnado, dust devil, fire whirls, steam devil: tornadoes range in size, speed, and composition, from a monster prairie sucker to lambent dancers on a warm water lake. They are as ubiquitous as they are varied, observable on every continent except Antarctica.

Tornadoes absorb the color of the environment they emerge from. Blood red funnels rip up rust colored soil in the Great Plains, while waterspouts turn into white and blue vortexes like a vertical tidal wave. It is said tornadoes back-lit by sunsets turn the color of fire, spiraling red, pink, and orange. A tornado back-lit by sun appears pitch black, while the same tornado, viewed with the sun at the looker’s back, adopts a blinding white and grey. Tornadoes have a calm center similar to the eye of a hurricane: serenity in chaos, an axis of peace for turmoil to pivot off.

Due to the land’s unique topography, the United States experiences more tornadoes than any other country. Without a major mountain range running from east to west, air flows freely from the equatorial waters of the Gulf to the artic landscape of northern Canada. The Rocky Mountains disrupt the atmospheric flow, creating a dry and low-pressure pocket to the range’s east. Warm air coming up from the Caribbean Sea collides with cold wind flowing down from the tundra, joining forces in the dry line known as Tornado Alley – think Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska. Tornadoes are most common in spring, the season of renewal. Opposites merging, cold and warm, destruction and birth: they live as a five-minute paradox.

*

Jarred came, as he, Shale, and I were a small and interdependent family. He loved her as much as I did and we mourned over the lifeless dog held within the swaying grass. We returned home and dug a grave beneath her favorite tree, her lookout point. She was a guard dog, as Keeshonds were bred as watchers of Dutch barges. She fancied herself so, in the least, and in honor of her devout vigilance we fought through tree roots and small boulders to dig a grave four feet deep. Jarred closed her white-haloed eyes and in she went along with a fistful of mountain wildflowers. We threw the fecund earth on together, burying our beloved Shale after two years of life.

Of course I blamed myself. During the grieving process friends and family assured us she died for a reason, a purpose we must decipher. As if I could see through the debris of sorrow into a tranquil eye and know that it was not my fault she died; that there is a peaceful center life pivots off of, hiding behind the chaos and beyond our control. I imagined her carcass seeping into the soil through the fecal matter of larva and worms and the maceration of runoff. I imagined her ghost lying atop the mound of shoveled dirt, her ghost standing behind the horse fence, watching. I sought that eye, yet only found a void.

*

Climate change contributes to the creation of strong storms, such as hurricanes, which also spawn tornadoes and floods. Rising shorelines result in more tornadoes as oceanic temperatures gradually increase. At the turn of the century the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) released a report compiled by the Institute of Environmental Studies in Amsterdam anticipating the rise of natural disaster frequency and intensity as a direct result of climate change. It was met with scientific scrutiny and public ambiguity.

The authors of the report hesitated to link weather irregularities to human induced climate change. Yet they could not deny the direct correlation between the rise of natural disasters and an exponential increase of greenhouse gas emissions since the Industrial Revolution. Head of the WWF Climate Change Program, Dr. Ute Collier, told BBC radio following the report release that “the world faces a stark choice – reduce emission or face the fury of nature.” Yet global carbon emissions continued to rise, increasing nearly thirty percent since the report’s debut.

*

I loved Shale like a child, a sentiment shared by many pet owners. The guilt and grief I harbored remained months after her death. I teetered between nostalgia and depression, spending a lot of solo time on hiking trails. She was just a dog, I tried to remind myself. Not a son or daughter. Not a human being – so why was I unable to rise from despair?

Weather remained volatile until mid-July. Then, beetle kill. We watched the mountainsides slowly expose red wounds as Lodgepole pines succumbed to an army of innumerable tiny incisors, gnawing the trees to death. Fall commenced the gorging of grizzlies with a dusting of frost atop mountains in early September. Their main source of protein and fat, cones of the Lodgepole Pines, proved hard to come by this year. Starved and panicked, the bears sought out survival with winter creeping down the peaks. This was the fall when a mother grizzly—desperate to obtain enough subsistence for her cubs to last the winter—assaulted tents in a campsite just outside of Yellowstone. Tents filled with sleeping people.

*

How to fathom the extent of nature’s wrath? There are vague premonitions of what is to come, studies indicating more hurricanes and tsunamis and earthquakes on the bleak horizon. Before the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth century, natural disasters existed in the undiscerning, godly realm. Tornadoes, earthquakes, and forest fires were interpreted as the acts of an angry deity. Many ancient cultures, such as the Greeks and Incas, tried to appease the gods in an attempt to obviate deaths caused by the fickle elements of water, earth, fire, and air.

We view ourselves as masters of nature, puppeteers with strings attached to life’s vital necessities like food and water. If our actions are indirectly causing the climate to change, then we are in a deviant way the gods our ancestors feared and implored to take mercy. Our relationships to nature are simultaneously filial and tyrannical, being both dependent on and domineering towards our various ecosystems. Natural disasters bring us back to earth. We cannot fathom the extent of nature’s wrath, because we refuse to collectively acknowledge the extent of our own transgressions.

*

The 300-pound mother bear attacked at night alongside one of her three cubs. She dragged Kevin Krammer, a father of four from Michigan, out from his tent to his death. Paramedics rushed two other campers to the hospital. It was a highly unusual event, as most grizzly attacks occur when a bear is caught off guard or feels her offspring to be threatened. Wildlife officials managed to find the four family members, killing the mother and keeping the cubs captive—not to be returned to the wild after such a tarnished upbringing.

Man dies in the jaws of bear; bear dies in the hands of man. The obvious member to sympathize with is from our own species. Yet what about the mother, outraged with hunger? The tragedy unfolded during the season of hyperphagia (when bears eat mass amounts of calories to fatten up for hibernation). Diminishing numbers of Lodgepole Pine cones force grizzlies to seek other sustenance.

Entomologists attribute the overabundance of pine beetles to climate change. Cooler summers limited the populations to low elevations and a single two-week mating season. With rising temperatures, the beetles manage to move up mountains and breed more than once, consequently devastating entire Lodgepole Pine populations across the continent. Would you condemn me a misanthrope if I also sympathized with the grizzlies as victims of industry?

*

In spring, 2011, the American Midwest experienced nature’s wrath as tornadoes ripped across the Great Plains at record-breaking velocities. On the 22 nd of May a mile-wide, multiple-vortex tornado rampaged Joplin, Missouri. It killed 116 people and left a third of the city beyond recognition. It was the deadliest tornado in half a century, and resulted in nearly three billion dollars of damage. We resurrected buildings, roads, schools, and hospitals: yet the loved ones lost live on in voids surpassing discernable purpose. We seek the eye of the tornado, but are swept away by grief.

The government’s National Severe Storms Laboratory described the 2011 tornado season as “deadly, record-breaking, and heart-breaking.” The unpleasant truths of climate change can no longer be ignored as our nation deals with the unpredictable consequences of our fossil fuel addiction. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published a paper in early August, 2012, declaring climate change as no longer impending. We now find ourselves in the thick of it: smoldering summers will soon be the norm, erratic and deadly weather patterns to be expected.

It is then hard to imagine why we continue to live the way we do, seeking extremes such as tar sands mining and fracking, despite the local and global catastrophes such practices leave in their wake. The tornado in Joplin is just the tip of the melting iceberg.

*

Human resilience is both an evolutionary adaptation and a gift. If we can keep breathing after the death of loved ones, after the decimation of entire towns, then certainly we can change our way of living. It may seem easier to continue manipulating nature instead of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But after the flooding in Vermont, the hurricane in New Orleans, the tornado in Joplin, will we carry on believing that the way we live is safe and sustainable? Comfort and security are not the same things.

The love I feel for Shale is part of a deeper craving for connection with other species. It is no coincidence that the World Wide Fund for Nature, an organization fighting the plague of extinction, is the same organization that published a report on the human vulnerability in an instable climate. Human deaths make headlines; yet the daily passing of entire species remains an elusive fact. Would we mourn the extinction of grizzlies, even when they may eat us? Given the current popularity of the polar bears’ struggle for existence, such an occurrence would not go unnoticed and without despair.

I am writing this as a modern woman – a woman who drives a car, types on a laptop, washes her clothes in machines. I see myself in the big picture, and I know I am right there in the thick of it, a product and producer of industry. I am caught up in the tornado of the everyday. I use the dishwasher to save time, and watch television to kill it. I, too, am often swept up away from the eye of the tornado, too blind to see that my consumer habits only contribute to the irreversible losses that pass unacknowledged every day. The car that I drive is the car that killed Shale.

To make purpose of her death I turned inward to a calm center while life continued to spin around me. I can only imagine that the survivors of Joplin and the loved ones of Kevin Krammer continue to seek peace as the world moves forward recklessly, without hesitation. What degree of tragedy will it take for us to acknowledge that the way we are living no longer makes sense? The day Shale died was the day I committed to reducing my dependency on fossil fuels. If there was purpose to be deciphered, I live on in full faith that this is it.

© Kelsey Sather

Shearon Harris Nuclear Power Plant

by Kelly Jones

Right now Kelly lives in the Lower Mississippi Watershed of New Orleans.

The school bus took us

to the underbelly

of electricity,

to learn

what made lights

come on

when we flipped a switch:

cores, coolant, technicians,

an emergency lake

that security guards

let us picnic by.

One of us asked about bombs

(Hiroshima, Nagasaki).

The tour guide explained

the future is nuclear and safe.

My friends work at that plant now,

understand that the white cloud

always in the distance

comes from cooling towers.

Their kids ask questions

that don’t get answered.

My friends teach me more

than tours ever did,

things I’d rather not know:

A fault line runs under Harris Lake.

Three risks of meltdown:

cracked reactor, leaky condenser, faulty turbine.

Nuclear evacuation signs:

just there for peace of mind.

© Kelly Jones

The Extinction Stories: The Labrador Duck

by Daniel Hudon

Daniel lives on the East Coast, not far from various nesting sites of the endangered piping plover in the Charles watershed.

Little is known of the Labrador Duck. Its breeding and mating habits, migration routes, nesting and biology all went unstudied. Perhaps they nested on small, rocky islets off the coast of Labrador. Or perhaps on islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. No one described the call of the species.

It was known to taste poorly, with a strong flavor of shellfish. Its bill was colorful: orange with a blue-black tip. The males had a striking black body with black and white wings, a white neck and head topped by a black patch. The female was gray-brown, had white on her wings and a light line behind her eye.

Naturalists disagree on whether the bird was trusting or wary. And whether the last one was shot in 1871, 1875 or 1878.

© Daniel Hudon

The Furnace

by Patti Capel Swartz

Patti grew up and currently lives in the watershed of the Middle Fork of Little Beaver Creek Wild and Scenic River, a part of the watershed of the Ohio River. Her office overlooks the Ohio between Southern Ohio and the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

When I was a child, the furnace sat, a behemoth, in the cellar, roaring when Mother shoveled coal, its uneven heat allowing us relative comfort in winter. Coal rattled down the chute into the shiny black pile that fed our house.

When coal ran out I rode with father to the strip mine, curving round and round the pit where machines cut into the earth exposing the “black diamonds” that filled the pick-up bed.

Close to our house, less than a mile across the fields, the night filled with lights and noise, shovels creaked, bulldozers roared when a field close to our house was stripped. We slept fitfully to the sound of the machines. Stripped out, topsoil under subsoil, my friends and I were forbidden to go there in fear of acid water. But we went, sneaking up the road, leftover shale crunching underfoot, walking mounds of earth that would grow nothing, staring into ponds where no frogs, no fish lived.

Soon new lights will disturb the country quiet of my home as derricks fracture old seams releasing gas from shale. They, too, will create water in which nothing can live.

© Patti Capel Swartz

The Lake in Winter

by Jerry Dennis

Jerry lives in the Grand Traverse Bay watershed of northern Lake Michigan, where he earns his living writing about water, weather, trees, birds, fish, and the people who care about them.

(January, Cathead Point, near the tip of Michigan’s Leelanau Peninsula)

It changes every moment. It is a thousand lakes, changing faces with every shift in wind and light – flurried by offshore wind, white-capped in squalls, colored flannel gray or pearl white or stormy black beneath the winter clouds, a dozen blues when the sky is blue.

There’s a contemporary Japanese poet who writes a diary on a slab of stone instead of paper, with water instead of ink. He writes a word, and a moment later it evaporates. This, he suggests, is the true record of a life.

*

We go to the shore in search of elemental things. Probably it is just coincidence that the elemental things we find there -- sand, sun, wind, and waves -- correspond exactly to the four elements of the ancient Greeks and Hindus -- earth, fire, air, and water. More to the point is that we need elemental things to keep our primitive senses in working condition. We need periodically to look, listen, scent, taste, and feel our way through the world, if only for the relief of not having to think our way through.

It’s not always an easy task. Time coats us in natural increase, accruing layers as if we were snowballs rolling down a hill. Jobs, families, friends, houses, cars, dogs, our health – just maintaining it all is full-time work. Add the bulging files of information, the gunnysacks of mistakes and the duffels of misjudgments and the barrow-loads of memories, habits, regrets, opinions, prejudices, principles, laws, and codes collected in a lifetime, and you can see the problem. We carry as much as we can, and the rest we stack around us until all our routes to the outside are blocked. Even when we find our way out we’re wearing too many layers of tuxedoes and zoot suits and cardigans, Icelandic woolens, parkas, longjohns, thermal socks, etc. We’re strong but we grow weary of lugging that Collyer-brothers’ accumulation everywhere we go. We bend beneath the load, our backs about to break, groaning as we push our heaped-up grocery carts through the streets.

It’s too much. Now and then we need to strip down to the naked flame at our core so we can remember what it feels like to be alive. Most of what we carry is baggage anyway -- just adornment and vanity, ballast and deadweight. It’s the crap the pioneers threw out along the Oregon Trail.

*

After lunch I walked to the crest of the dune and looked out at the lake. Even from that small elevation, maybe fifty feet, the water’s clarity was startling. From a boat, on a day like this, with the sun overhead, you can lean over the side and see boulders on the bottom thirty feet down.

The pale shallows stepped into blue depths. The offshore sandbars were there, a hundred yards apart, each deeper than the one before, with bands of increasingly darker blue between them. Beyond the last bar a steep drop-off into very deep water turned the water midnight blue.

Lake Michigan. My lake, I often think, because I grew up near it and because so many in my family settled along its shores. So much water, in a body so large they say that the Netherlands could fit inside, with enough room left over for several New England states. It is the second largest of the Great Lakes in volume, and third, after Superior and Huron, in surface area. It is the only one of the five to be contained entirely within the United States.

Most of the 1,640 miles of shore is sandy. Some of that shore, especially around the southern end, through Indiana and Illinois, is lined with industry. Around the top of the lake in Wisconsin and Michigan are limestone bluffs and rocky strands. But most of the rest is blond sand beaches that are among the loveliest in North America. Wind, waves, and ice have shoved that sand into the most extensive network of freshwater dunes on the planet. They reach their apogee about thirty miles south of Cathead Point at Sleeping Bear Dunes -- the most beautiful place in America, according to “Good Morning, America,” and I don’t disagree -- but they extend nearly unbroken for three hundred miles along the eastern and southern shores of the lake, from northern Michigan nearly to Chicago. A few scattered dunes are found also along the Wisconsin shore and at the top of the lake, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, but they lack the dimensions of those that face the prevailing winds.

A friend who lives part of every year in the West once told me that Lake Michigan plays the same role in the Midwest that the mountains do in Montana. That’s true for all five lakes. Like the Rockies, you can see them from miles away, forming a backdrop that is also a felt presence, always there, looming in our lives. They are depositories of geological and historical power that shape the land and the culture to themselves. We orient to them and are drawn to them and take for granted that their presence and the weather they create will affect our travels and alter our daily plans.

The lakes have always been the most prominent shaper of the character or “spirit” of the Great Lakes region. The stronger the spirit of a place, the farther it resonates beyond its borders. Alaska, Texas, Vermont, and Maine all have it in abundance. So do large geographical regions such as Appalachia, the Canadian Maritimes, and the swamplands of Louisiana. A mythological portrait of a place needs to be only approximately accurate to give outsiders an idea of what it is like, or enough of an idea, anyway, to inspire interest in it. That might explain in part why people who have never visited the Everglades or the Arctic Wildlife Refuge are willing to write letters to congressmen and donate money to protect them.

The Great Lakes have not had that advantage. Their mythology is not clearly defined. It was once very clear, a living mythology, inhabited by people, wolf, moose, and bear, but the stories that passed around campfires for thousands of years were drowned out by European invaders wielding their own stories of Jesuit martyrs, French voyageurs, Paul Bunyans of the logging camps, mariners of the inland seas, and up-by-the-bootstraps giants of industry. Most of those stories have now, in turn, lost their power and have not been replaced. Enduring mythologies tend to accrue to dominate features of a landscape. Louisiana has swamps; New England, hardscrabble hills; Montana, big sky. But the Great Lakes are too varied. No representative image fits. The water and dunes and rocks and cities on the shore are lost in a haze of homogeneity. Surely that is why those who have never stood beside the big lakes find it so difficult to imagine them.

-End-

Excerpted from The Windward Shore: A Winter on the Great Lakes, by Jerry Dennis (University of Michigan Press)

© Jerry Dennis

The Wintering Birds

by James Eret

James lives with his family, two feline friends, and an ever-expanding menagerie of wild visitors to his urban oasis in the midst of the all-too-urban San Diego watershed.

My aunt is weary, knowing

in the biology of her bones

that at eighty-four the leaking heart valves

will shut down soon. She dreads

that final wrinkling

of her natural organism,

a process she has studied long and well,

teaching us the fine-tuning

of the green kingdoms.

Every time she ascends her hill,

the lace-delicate valve opening and closing

the gates of her blood

falter and remind her

of the weakness of her flesh,

the way age comes on like a Midwest blizzard blowing

in its crystalline beauty and brutality.

Hidden predators hibernate in dead cherry wood logs.

Their pulses slowly lift their lungs.

She rests too often and with restless sleep.

Snowbound, she watches, for the last time,

the wintering birds,

the blood-red cardinals stabbing

at the sunflower seeds in the feeder,

dangling by a thread

above the deeply-frozen snow.

© James Eret

Where the Radiation Goes

by Lucille Lang Day

Lucy lives in the San Francisco Bay Delta Watershed, which covers more than 75,000 square miles. Her particular corner of this vast watershed is the watershed of Pleasant Valley Creek, which unfortunately now runs mostly under Grand Avenue in Oakland.

When an earthquake cracks

a reactor, iodine molecules

ascend. Tumbling in hot wind,

they drift to a grassy slope

where mottled cows graze.

Soon children will drink milk

that scintillates like a galaxy.

A woman opens an umbrella,

as broccoli, lettuce, mustard

and spinach are suddenly

bathed in strontium rain.

There’s nowhere to go except

earth, sky, and sea—algae,

fish, clouds, birds, trees.

Radiation from a test in China

ends up in Utah and Colorado.

Fifteen years after Chernobyl,

the isotopes were still found

in stalks and delicate gills

of wild mushrooms gathered

by picnickers in France.

© Lucille Lang Day

The Inspired Pen of a Wildlife Warrior

by Barbara Lee

Barbara lives close to a newly restored wetlands that connects to the Willamette River in Eugene, Oregon. Chinook fingerlings are sheltering in these wetlands for the first time in 60 years. She also works as a seasonal volunteer in Yellowstone National Park in the corner where the Yellowstone River, the Gallatin Range, and the Gardiner River come together.

Oh, puny Man, wouldst thou atone

for years of swelling ego heart?

Go tread the mountain-top alone

and learn how very small thou art.

from “Wild West, Spell of the Mountains”

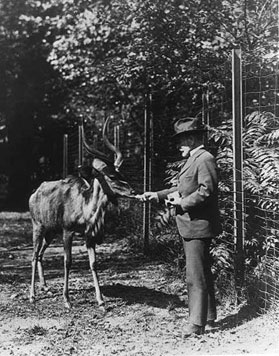

Surrounding Yellowstone National Park’s Lamar Valley are mountains with names like thunder claps: Druid. Abiathar. Baronett. The Absarokas. Among these peaks is little known Mount Hornaday, bearing the plain name of a man who battled for decades to save America’s vanishing wildlife. William Temple Hornaday was famous in his time, but now, like the mountain, receives little attention.

Born in 1854, William Hornaday was a prominent zoologist who during his long life was also a taxidermist, hunter, museum director, and prolific writer. His great passion was the protection of vulnerable animal species, and like his good friend Teddy Roosevelt, a love of hunting and collecting evolved into action to halt the ongoing slaughter of vast numbers of wild animals.

One way that Hornaday brought wilderness to the attention of the Victorian era public was through unabashedly melodramatic poetry. The author placed readers on snowy crags where creatures were brave, even gallant, in the face of nature’s extremes:

from “The Rocky Mountain Sheep”

His home around the mountains frowning crest,

Where lines of rugged rock stand forth,

Where Nature bravely bares her breast

To snowy whirlwinds from the north.

High in the clouds and mountain storms,

Where first the autumn snows appear,

Where the breath of springtime last warms

There dwells my gallant mountaineer.

William Hornaday saw himself as a warrior on behalf of all threatened wildlife, but saving the bison from extinction became his signature effort. By the turn of the century very few of the animals remained, and in 1905, Hornaday and Teddy Roosevelt formed the American Bison Society in order to prevent the disappearance of the species.

Efforts to protect, re-introduce, and increase the number of bison gradually succeeded. One well-known project took place in Yellowstone, home to the two dozen animals that made up the last wild herd. In 1907, the herd was moved to a newly built buffalo ranch in the Lamar Valley to ensure the animals’ survival and form the nucleus of a growing population. Hornaday’s fierce verse asked what kind of society would slaughter the bison to the very brink of extermination:

“The Buffalo”

We went at the millions outrageous, thinking they always would stay,

and before we knew we were wicked, they totally vanished away.

William Hornaday’s old-fashioned style hid a good deal of modern content. A century ago, Hornaday’s poetry argued the radical philosophy that wildlife was more than just a resource to harvest, and that a landscape robbed of animal life was soon desolate. Hornaday’s tribute to the pronghorn antelope pictured a setting where greed and ignorance brought on the loss of every living creature down to the last wolf.

from “The Antelope”

The rifles and greedy old game-hogs,

the barbed wire fences and snow —

I shore hate most awful to lose him,

but I guess that he's bound to go.

No living thing in sight, no creature near

To break the desolation of the scene.

The black-tailed deer have fled before the gun.

The antelope were slaughtered, one by one.

The last lone wolf lies crouched

in hungry fear in yon ravine.

In Yellowstone, the Lamar Buffalo Ranch still stands in the valley ringed by peaks, but the log cabins and bunkhouse are now used for educational seminars. Most people wouldn’t guess that this quiet spot was the location of one of the most famous wildlife projects in the country’s history.

President Frankin Roosevelt recommended that a Yellowstone peak be named after Hornaday to honor his work to protect America’s vanishing wildlife, but the naming did not occur until 1938, the year following Hornaday’s death. It’s too bad. You can imagine the old Wildlife Warrior gazing at Mount Hornaday and out over Lamar Valley, now populated by grazing bison, and then penning a verse something like this one:

From “Spell of the Mountains”

Toil to the top of cloud-kissed peak

and see vast seas of mountains roll.

Then feel great things thou canst not speak

Because of smallness of the soul.

Further reading...

Many of William Hornaday’s books are still available, including several that are free in electronic form. Poems in this article are from Old Fashioned Verses by William T. Hornaday (1919).

There is a recent biography of William Hornaday, Mr. Hornaday's War: How a Peculiar Victorian Zookeeper Waged a Lonely Crusade for Wildlife that Changed the World by Stefan Bechtel (2012)

© Barbara Lee