Issue Number 24, Spring 2014

Contents

- They Feed They Lion by Philip Levine

- Abbreviated Geography by Paal-Helge Haugen

Translated from the Norwegian by Damon Aukema - Arribada: Arrival of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles by Maya Khosla

- Dragonfly, Shelling by Clara Quinlan

- Eleven Daffodils by Meryl Natchez

- Extinct: Laughing Owl

Sceloglaux albifacies by Holly J. Hughes - Giant Pandas by Daniel MacIsaac

- Leave Taking by Gail Rudd Entrekin

- Letters from the Hinterland #8, Toxins by Raymond Greiner

- Musings from the Silence at the Vedanta Retreat in Olema, California.

What's a Weed? by Carolyn North - North Woods by Monty Jones

- Promethea Moth by Margot Farrington

- Seeing, Choices by Sarah Fawn Montgomery

- The Blessing by Michael Hettich

- The Day After the Storm by Amber Foster

- The Extinction Stories: Orange Band, The Last Dusky Seaside Sparrow by Daniel Hudon

- The Gold Tongue by Barbara Daniels

- The Potteries by Patti Capel Swartz

- Vigil for the Leatherback by Paul Belz

- Winged Victory by Wendy Williams

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

They Feed They Lion

by Philip Levine

Philip now divides his time each year between the San Juaquin River valley on the West Coast and the Hudson River watershed on the East Coast.

Out of burlap sacks, out of bearing butter,

Out of black bean and wet slate bread,

Out of the acids of rage, the candor of tar,

Out of creosote, gasoline, drive shafts, wooden dollies,

They Lion grow.

Out of the gray hills

Of industrial barns, out of rain, out of bus ride,

West Virginia to Kiss My Ass, out of buried aunties,

Mothers hardening like pounded stumps, out of stumps,

Out of the bones' need to sharpen and the muscles' to stretch,

They Lion grow.

Earth is eating trees, fence posts,

Gutted cars, earth is calling in her little ones,

"Come home, Come home!" From pig balls,

From the ferocity of pig driven to holiness,

From the furred ear and the full jowl come

The repose of the hung belly, from the purpose

They Lion grow.

From the sweet glues of the trotters

Come the sweet kinks of the fist, from the full flower

Of the hams the thorax of caves,

From "Bow Down" come "Rise Up,"

Come they Lion from the reeds of shovels,

The grained arm that pulls the hands,

They Lion grow.

From my five arms and all my hands,

From all my white sins forgiven, they feed,

From my car passing under the stars,

They Lion, from my children inherit,

From the oak turned to a wall, they Lion,

From they sack and they belly opened

And all that was hidden burning on the oil-stained earth

They feed they Lion and he comes.

© Philip Levine

Abbreviated Geography

by Paal-Helge Haugen

Translated from the Norwegian by Damon Aukema

Paal-Helge is a Norwegian poet, novelist and playright.

Damon lives in Red Wing, Minnesota, in the Rush-Vermillion watershed and within walking distance of the Mississippi River.

Forests grow up

from the map, first as a thin film

of green earth with distant footsteps

and cries, rivers overflow their banks

and soak the paper, the wind sweeps in

and out between its pages, with wingstrokes

and rippling when sun and rain rewrite everything

again as the sand spreads, sifting

down over continents, and on the sixth day

a barely visible streak

of smoke, day of fire and ashes

before the seventh day, when the forests stand

gray and defoliated, ready to judge

the living and the dead.

© Paal-Helge Haugen

Translated from the Norwegian by Damon Aukema

Arribada: Arrival of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles

by Maya Khosla

Maya lives near Copeland Creek, which is a part of the Russian River watershed in Sonoma County.

Because desire and perfection are tangled forever in darkness,

those who emerge are offspring of an edge

whose salts and sighs echo the waves.

The night rising and sinking under phosphorescence

churned into being

with each wave’s crash and sizzle. A map of cold

green light from which mystery

must surface to breathe, must swell

to the shape of a thousand strangers,

a thousand more. All clothed in submarine suitcases

heaped with expectation.

No choice but to sink to your knees in sand

terrified that life, laden with all her pearls of tomorrow,

could lose her lumbering grip on the world.

And though the turtles cannot afford

to care about perils, evolution does.

And so has created this mad saturation—

so great you could walk miles on their shells

and never touch sand.

Such is persistence. It has no choice but itself,

older than the Jurassic moment

when females began this flipper-footed scraping,

this egg-laying labor, eyes gazing seaward

vertical eyelids opening, shutting, opening

full of tear-gel.

© Maya Khosla

Dragonfly, Shelling

by Clara Quinlan

Clara lives in the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, where Longs Peak looms in the near distance and Coal Creek cuts dramatically across the land.

How silver clings to the dawn the rain

Stammering, its threaded wings

under the wind see we all hold on

with our many arms iridescent

larvae curled against the underbelly of pier,

magenta sheen, flecks of blue,

tiniest instance of

something I might walk toward

were I lost, were this water

across the anviled world to carry me

no longer

Its chitin shell with shape with eyes

emergent as it could be again in this stirring –

harmony soft of scraping leaves

soon dripping, sound

to be numbered and the tattered shore

radiant with the born

Come closer

as if this eased the possession

deliver yourself hapless

each falls into the lapping but for the one

in your palm, taut-winged, transmuting the light.

© Clara Quinlan

Eleven Daffodils

by Meryl Natchez

Meryl lives overlooking coast live oaks that line the canyon of Cerrito Creek as it flows into the San Francisco Bay.

What am I to make of these daffodils,

perfumed strumpets

picked who knows where

by who knows whom

perhaps genetically modified,

commercially fertilized,

doused with pesticide?

These questions did not arise

when I tossed the budded stems

into my shopping cart

on a chill afternoon:

essence of Spring

for a dollar twenty-nine.

Now they sit

and pump out scent,

molecules of daffodil

mixing with molecules of oxygen

around my desk

until I am dizzy

with praise

and regret.

© Meryl Natchez

Extinct: Laughing Owl

Sceloglaux albifacies

by Holly J. Hughes

Holly is happy to have landed in the Chimacum River watershed at the foot of the Olympic Mountains on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington. For the last 30 years, she has spent part of each summer working on boats in the waters of the Alexander Archipelago of Southeast Alaska.

A hundred years ago, on dark nights, their laughter

echoed over the green fells of New Zealand.

The settlers say the haunting notes of their laughter

--they called to each other -- came minutes before rain.

Languid during the day, the white-faced owls

were too easy to capture. They fed on a native rat,

the kiore, whose extinction brought on their own.

In 1905, a settler told how a laughing owl could

always be brought from its hiding place in the rocks

after dusk by the squeeze and wheeze of an accordion.

He told how the owl would silently fly over, face

the music, listen until the music ceased.

Inspired by Swift as a Shadow: Extinct & Endangered Animals by Rosamond Purcell.

© Holly J. Hughes

Giant Pandas

by Daniel MacIsaac

Dan lives and writes in a home overlooking Witty's Lagoon on Vancouver Island.

Ailuropolda melanoleuca

These are contrary creatures,

carnivores evolved to live on shoots,

bearcats that the Ming Chinese

believed ate copper cooking pots.

Bulky as beer kegs,

they must slip each hemp-line snare

then dodge each hunter’s blind,

becoming addled blurs

to the snakehead’s eye.

Jailbirds, blackpatched

lifers hostage

to the flowering

of bamboo,

under house arrest

they pace, tagged

and monitored,

kept to high ground

by slash and burn.

Tinged snowdrift

and deep treeshade,

they just blend in,

knowing their place.

Shy cousins

to burly cave bears

they slink through Time,

discrete and buttoned-down

as butlers.

© Daniel MacIsaac

Leave Taking

by Gail Rudd Entrekin

Gail lives amid the Coastal Range east of San Francisco Bay in the San Pablo Bay watershed just above San Pablo Creek on lands of the Chocheno and Karkin Ohlone people.

Everywhere the planet

is pulling in her generous green

folding it up forever in the vast trunk

of history. She is taking down the curtains

of rain and giving them away to someone

in another dimension who will treat

them gently. She is rolling up

the atmosphere with its cigarette holes

and moth-eaten diatribes and when

she has packed her bags and slammed

the door and left us looking at each other

in silent shame, like bad children,

we will say, We didn’t do it.

It was someone else.

© Gail Rudd Entrekin

Letters from the Hinterland #8, Toxins

by Raymond Greiner

Raymond lives with his canine companions Orion and Venus on 14 acres of remote forested and pasture land about three miles from the hamlet of Paragon, Indiana, in a cabin about 500 yards from the little-traveled road.

The nightly radio show “Coast-to-Coast AM” spent an entire program interviewing experts and discussing a profoundly important and interesting issue, the modern agricultural practice of using chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides. Decisions to advance this technology were made solely from a perspective of economics: higher yield, faster field management, less cost to cultivate, more dollar return relating to time and equipment operating costs. Long-term effects were not considered. Profiteering has found a home in modern, large-scale agriculture. Economics has trumped logic, which forms a destructive, controlling force, oblivious of consequences.

Honeybees are dying off rapidly because they ingest toxins that attack their nervous systems from the chemicals used in modern-day farming practices. Beekeepers are losing in excess of 20 percent of their bees annually as a result. Honeybees are important far beyond the manufacturing of honey. Bees are vital to pollinate crops and wild plants. Weeds mutate, building a resistance to the chemicals and causing the chemical companies to increase the toxicity levels of the chemicals in order to counter the weeds’ mutations. Because honeybees are farmed, the noticeable decline in their numbers is more evident and alarming. However, there are many more species of pollinators that are likely suffering decline on a level similar, or even greater than the honeybees’. Orchard bees, bumblebees, syrphid flies, pollen wasps and hummingbirds don’t get a head count, because they don’t manufacture honey and do not contribute to economics in a directly impacting manner.

Where I live, each spring I see farmers pulling trailers with large tanks of chemicals to be sprayed on their fields. As these chemicals are sprayed year after year, the soil becomes contaminated and the toxins are absorbed into the crops, which are ingested by humans. This system is solidly in place with no sign of change or discussion by those capable of implementing change. Monsanto heads a powerful lobby group whose goal is to block legislation that can address the issues of chemical poisoning of the soil and thereby the populous. Money and profits are addictive elements of power and influences capable of destructive patterns. The question is: Are the farmers’ bank accounts and the corporate bottom line more important than human health and well being? Our food chain is being tampered with and little or no consideration is applied regarding long-term effects.

How can ecosystems flourish without pollinators? Organic farms adjacent to chemically dependent farms are influenced by the destruction of the bees. Bees were kept for their value as pollinators as far back as ancient Egypt and now are being threatened by a quest for wealth. Without pollinators we will experience devastation equal to any in human history. Technology is here to stay, but it is ever increasingly important that we learn where the boundaries are located separating benefit from ruin.

© Raymond Greiner

Musings from the Silence at the Vedanta Retreat in Olema, California.

What's a Weed?

by Carolyn North

Carolyn lives between the Derby and Temescal watersheds on the east side of San Francisco Bay.

The word “weed” generally refers to a plant not valued for use or beauty, that grows wild and rank and hinders the growth of superior vegetation. One dictionary defines weed as an “unprofitable, troublesome, or noxious growth, a plant considered to be a nuisance. The word commonly is applied to unwanted plants in human-controlled settings or any plants that grow and reproduce aggressively and invasively.” In other words, a plant smart enough to know how to survive no matter what, that takes advantage of whatever the world offers it to live.

I’ve been weeding in the Vedanta garden, often wondering what to pull and what to keep. The roses and azaleas I know are keepers, and the iris, just past, and the lavender bushes. The intruding grasses have got to go, but just a few yards away in the meadow they are native, at home, welcome. Poppies as well, although once they invade the cultivated beds they make themselves quite at home because, well, they are at home. This is their turf, as it is for plantain and clover, mullein and dandelion. I grab a handful of bindweed, amazed by its tenacity and the range of its roots, and I find myself mentally apologizing to it when I toss it onto the dead pile.

I want to applaud all these weeds for their cleverness in snuggling up close to the cultivars, the “superior vegetation” that receives regular watering, where they can, for awhile at least, mask themselves and drink their fill. At least until some human with an attitude – like me, for example – comes along and yanks them out.

It’s true, though, that the stunning show of the exotics’ white and bright red, deep purple and orange against the greens of the garden shows the glory of flowers more vividly than the subtle shades of the dry dirt natives, but who is likely to survive when the water and the weeders run out? Given a season or two of non-interference, which plants are likely to still be here, providing medicine for the soil and whatever humans are still around, and which plants will have dropped their leaves in a last, sad hurrah? (Plaintain: skin abrasions, laxative. Clover: antispasmodic, anticoagulent, diuretic. Mullein: sedative, anti-inflammatory. Dandelion: liver tonic, diuretic...)

So who decides what gets to stay and what must go, and by what criteria do we/they make our call? The big-time weeders cut down whole forests and shoot wolves from helicopters. Bears are almost gone and puffins have gone extinct. The local cops even shot a coyote who wandered into my town one night, probably disoriented, and I’m told that once eagles flew in these skies. Maybe we are the weeds, the noxious intruders who have reproduced aggressively and invasively, hindering the growth of a superior and diverse community?

Personally, I consider us humans rather gorgeous and remarkable additions to the world scene, but still in an infantile stage that doesn’t yet know when it’s OK to interfere with the natural order and when it’s simply stupid to do so. What ignorance about how it all goes together – or even that it all goes together! What will it take for us to learn to keep our hands to ourselves and our eyes and ears humbly open?

Balance. It’s all about keeping in balance with the world and the others here with us, becoming neither weeds nor weed pullers, but equal members of the whole enchilada, benefiting and being benefited in turn. What made us ever think otherwise?

© Carolyn North

North Woods

by Monty Jones

Monty lives within the highly urbanized Country Club Creek watershed in Austin, Texas. Country Club Creek is only seven miles long and flows into the Colorado River not far from Jones' house.

Chanced upon this one place no one else

wanted, camped among these red pines

beside the least-favored lake, for three cold nights

I have bent before a fire, scavenged branches

urged into flame, tired of finding things I can’t name

everywhere I look, to watch the blue light go down

and wait for the flight of the loon.

This one bird, a male, and the same one

I have seen in the full light far out across the lake,

where he drifts and rocks at a lazy distance

from the female and the two young,

so they are together and apart,

until somehow toward dusk he has been off alone,

far to the north, and begins his long return to them:

First and for a long time you only hear him calling,

a parody of the proper sound of a bird,

his cartoon laugh and then that long lunatic cry

until a loon appears above you, flying so low

above you and so fast, you hear his wings

thrash the air, until he disappears in the pines

and then flies on and on into the growing darkness.

Each night the loon makes the same mad dash home,

a thing to stand and wonder at – to hear him coming

all that time, announcing the fact of himself

from that great distance, and then at last

to see the staggering addle-winged flight

as he crosses above me where the branches part

in the darkening sky, and to think of how

he must sound to the ones across the water.

© Monty Jones

Promethea Moth

by Margot Farrington

Margot lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, two blocks from the tidal sweep of the East River--a major flyway for migratory birds.

On her wings she wore eyes of surprise, and was herself

an optic confection, for the hand of the moth god had

sugared her scant but sprinkled cinnamon without stint.

Caught, she beat like a book, pages flipped by wind.

No spider rushed to where she spun, tethered by gobbet

and thread. She’d snuff by exhaustion, dancing the

twirl-to-tatters waltz, fastened

trickily by one forewing so

how to loose but not to tear her?

Painter’s wife, I chose a brush

as from the Nether-Wherever,

Turner and Constable watched my strokes. Marin

pursed his mouth as I worked further under her

wing. When she dropped in the little bucket

cleaned for this maneuver, Kline and De Kooning

grinned. You secured the plastic lid, then handed

me her prison. Attuned, I registered no flutter,

yet each step felt seismic.

The bark good for camouflage, only a cherry tree

would do. Not this tree, I said, not that one,

as we crossed the lane, the downed fence. Did I say she

was big as a child’s hand, that our night light

drew her? Did I mention how she began as it,

strove awhile as he, how somewhere in the struggle he

morphed to emerge as she? Our theory of her sex

determined solely by the drama.

She clung a minute to the tree we chose.

Closed. Opened, throbbing slow. She flared,

flew us to field’s edge, and then she let us go.

Reprinted from Scanning For Tiger, (Free Scholar Press, 2014).

© Margot Farrington

Seeing, Choices

by Sarah Fawn Montgomery

Sarah lives on the Great Plains in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Choices must be

simpler for starfish,

who don’t see

the world

like you or me,

colors and shapes,

texture, movement,

each decision

influenced

by how images

conjure the histories

lurking somewhere

in our brains,

the way these shade

what we see, do.

No capacity

for memory, legacy,

starfish know only

light and dark,

eyespots tipping

each slender leg,

stretching out

pentagram

to glimpse

the wide world

only slightly,

choice merely

between shimmer

or shadow.

© Sarah Fawn Montgomery

The Blessing

by Michael Hettich

Michael lives on the Atlantic Coastal Ridge in the Biscayne Bay Watershed of South Florida, a mile west of Biscayne Bay.

Just to think of the much-loved pet dog lost

beside some strange highway, feeling he needs to

get across somehow; just to think of the raccoon

leading her kits up the turnpike ramp,

or the thousands of squirrels and pigeons flattened

like shadows. Think of us humans with somewhere

to go, moving quickly. And whose dog is that

lapping at the garbage in the alley, you know,

the one with a badly-healed leg that festers

with stink, who leaps away yelping when the father

walking along with his child, pretends

to kick the lame dog to make his child laugh

and teach him what’s funny. The dogs that so proudly

cross the rush-hour street as though

they were going somewhere, the opossums who shuffle

along our sidewalk in the moonlight with their babies

all safe in their pouches; we could think of them blessing

our sleep by passing, just think of them dreaming

all day while we work—they all dream, of course,

like we do, to process their lives, just as

they all had parents who grappled to make them,

and mothers who suckled and groomed them, each one.

© Michael Hettich

The Day After the Storm

by Amber Foster

Amber lives in the Brazos Valley region of Texas, along the green banks of Brazos River, the 11th-longest river in the world.

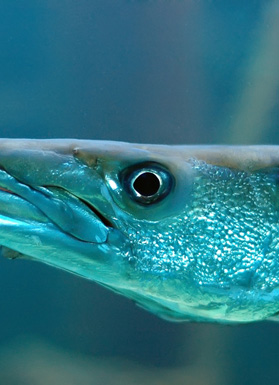

The barracuda stares at me with deep sea eyes.

You don’t belong here, those eyes say. What kind of fish are you?

At a hundred feet, we are enveloped in blue. There is no bottom, although it should be here, along with the wreck we have come to dive. The only sense of up and down comes from the bubbles of exhaled breath that mushroom up and away, expanding as they carve their way to the surface.

I’m lost.

Behind me, my two customers wait, pointing at the barracuda, their eyes wide behind their masks. It is not the wreck they have come to see, but it is something. They are a nice couple, Canadian, mid-twenties. I have spoken with them only briefly, long enough to tell them how deep, how long, what not to touch.

The barracuda is the largest I’ve encountered. Six feet, although maybe only five on the surface, without the perspective-tricks the sea plays. His teeth are large and sharp, designed to crack the bones of littler fish. He stares at me with grandfather eyes, his long, silver body crisscrossed with the scars of old battles.

Do you know where it is? I ask him with my eyes.

The boat captain took us along the rocky, wave-eaten coast for twenty minutes, and then turned off the motor. A plane of flat water, identical on all sides. Where’s the buoy? I asked, and the man shrugged, leaning back and pulling his hat down over his face.

I’m not supposed to ask questions. I’m a freelancer, a drifter. No one knows I have only been on the island a week and don’t know the way. With buoys, there are ways around not knowing, ways of plotting easy out-and-back courses until the labyrinths of coral become familiar.

But the storm came in the night, and sank the buoy and the line leading down to the wreck.

Without the buoy, I’m lost.

The barracuda swims closer, so close I can see the inside of his mouth, white like desert bones. I’m not afraid. He’s curious about these strange fish in his sea, fish whose bubbles fill the world with noise. In an instant he turns, and displaced water brushes my face, feather-like. I follow, pressing hard with my fins, trying to catch up, even though I know it is impossible. I wave for the customers to follow. In my peripheral vision I catch glimpses of bubbles, black wetsuits, pale knees bobbing above cheap plastic fins.

Ahead, the barracuda fades from view, merging with a great shadow that rises up from the sea floor. The shadow becomes the wreck, a heap of discolored metal resting on its side in the sand. A rusting corpse coated with a living skin of coral. From under the cargo hold, the green moray they call El Capitán peers at me, as if asking me why I am so late. I turn and look for the barracuda, but he’s gone.

Thank you, I say, speaking with eyes that look past the wreck to where the sunlight disappears into points of refracted light. Nearby, a broken mast lies half-buried in the sand. The coral-encrusted metal is like an old man’s finger, pointing out and down.

© Amber Foster

The Extinction Stories: Orange Band, The Last Dusky Seaside Sparrow

by Daniel Hudon

Daniel lives on the East Coast, not far from various nesting sites of the endangered piping plover in the Charles watershed.

In the jar, all is quiet. It can’t hear anything. No traffic, no mosquitoes, no rockets blasting off to the moon. The air is pure though sadly, the wind never blows. The marsh is long gone. Its blind eye lies open, unseeing in its green glossiness. Its head is pressed against the bottom of the jar, yellow beak closed, mottled feathers tussled. Just an ounce of bird, the few notes of its song unsung. A tag on its claw reads:

Dusky "Orange"

Last one

Died 18 Jun 87

© Daniel Hudon

The Gold Tongue

by Barbara Daniels

Barbara Daniels lives in the Big Timber Creek watershed, which drains into the Delaware River.

She wants to let the world

be the world, patient accumulation

of leaves, beautiful wheel of the sky,

slabs of rock an open book of mercy.

What she desires-gold tongue

of a purple iris, sweet light in trees.

A hawk turns, lifts its ragged wings.

She is her body, these lips, this hand.

Pink shrubs border the river.

Blossoms fill branches. Leaves

and grasses do not lack tenderness.

She sees that they never stop rippling.

© Barbara Daniels

The Potteries

by Patti Capel Swartz

Patti grew up and currently lives in the watershed of the Middle Fork of Little Beaver Creek Wild and Scenic River, a part of the watershed of the Ohio River. Her office overlooks the Ohio between Southern Ohio and the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

The Brownfields Law defines a "brownfield site" as:

...real property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance,pollutant, or contaminant." Brownfield sites include all "real property," including residential as well as commercial and industrial properties.

In the potteries’ heyday when East Liverpool, Ohio, was called the pottery capital of the world, women licked tiny paintbrushes to apply gold leaf to china, and glazes were bright from the lead. When pottery was misshapen or broken, shards were dumped in lots the potteries owned or on the riverbank leading to the Ohio River. Silicon filled the air, dust from the clay. Workers swallowed lead, breathed silicon, smoke from the kilns.

Thirty years after TS&T pottery closed, the buildings sat, still, hulks, reminders of a past when whole families shaped clay, painted, fired. Some men carried clay on boards resting on their heads, some ran wheels. Others loaded kilns, turning their faces away from the heat. Children packed china in barrels: plates, cups, saucers, bowls immersed in straw. At the plant’s close, buildings sat idle, although families lived in what had been an office building, and low-income housing developments mushroomed next to the site.

Then buildings, half razed, weathered for six years, asbestos insulation, open to the rain, blowing in the wind. Two silos that held clay and a smokestack stand. The skeleton of the plant reduced to piles of yellow brick stands above foundations under foundations, rooms below ground, a labyrinth needing to be filled.

Shards of pottery still dot the riverbank. Water courses down the steep bank, carrying its burden of lead. Children, their parents, their grandparents, aunts and uncles, drink water from the river. Birth defects,

Intellectual disabilities, and, of course, cancers rate the area highest in health problems. Cancer here is endemic.

Brownfields beget brownfields. Other dirty industries locate here. There is no way to prove blame.

© Patti Capel Swartz

Vigil for the Leatherback

by Paul Belz

Paul lives near San Francisco Bay, a habitat that is also home to red tailed hawks, redwood trees, raccoons, California newts, and skunks.

It's the crickets' chant,

the syncopated calls of five species

and the howler monkeys' cries

that call you to shore while we wait,

sleepy in the parking lot with our cheeks

on our knees and ours eyes blurred.

You ride the currents, the rushing tides

and we yearn for you, we children

of beach front property, of fishing trawlers

and plastic bags. We yearn to see

that you still live, great vagabond. We yawn,

sleep on the sidewalks with our arms

wrapped around our bent legs until the herald

of your arrival comes. We walk in silence

past guardian waves. They chant with the crickets

and monkeys. The biologist's red votive light

guides us to your side, great traveler. We squat

and kneel on damp sand while you drop eggs

into their shelter. They are round as cue balls,

ivory white and damp, all sizes in a pile.

You struggle with the land, water reptile,

you wrestle with gravity and your weight.

The ridges on your brown - green shell

don't balance you here. We surround you

and watch through the red darkness. We're

silent and motionless as your flippers wave

and toss sand on the eggs as shelter from raccoons.

You start to turn to face the ocean. We break our circle,

rise and move to let you be. Did you notice us

in your struggles, we children of DDT and oil?

You swim in our chests as we walk

single file and silent past the guardian waves

beneath the Geminid meteors and Orion,

our guide to the sky,

while crickets chant and monkeys sing.

Playa Grande, Costa Rica 12/13/01

© Paul Belz

Winged Victory

by Wendy Williams

Wendy lives close to the American River in northern California about two miles from Lake Natoma. The pelicans in the poem were flying north over Salt Point on the Pacific coast.

(a tribute to Rachel Carson, author of the book Silent Spring (1962), which exposed the dangers of DDT, among them the weakening of pelican egg shells)

How glad you would be

to see this

long line

of pelicans

one behind the other

skimming the ocean

their shadows

black mirrors

beneath

pelicans

arrowing

across the sky

in a long loose V

a front of pelicans

galloping toward me

over the plain of sky

fifty fliers

pumping wings

muscling their weight

into wind

one bird

trailed by

three fledglings

flapping wildly

to keep up

string after string

of birds

whose eggs

now hold

hatching

into wings

of wild

© Wendy Williams