Issue Number 36, Spring 2017

Contents

- Kaddish in the Anthropocene Era by Leah Korican

- Respiring by Gail Rudd Entrekin

- Animals in the Yard by John P. Kristofco

- Dear Future by Joan Baranow

- Bolinas Lagoon by CB Follett

- One Bird Falling by CB Follett

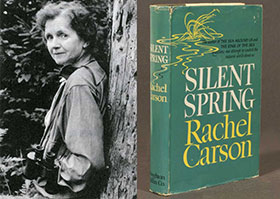

- The Death of Rachel Carson--April 14, 1964 by Donelle Dreese

- Night Caller by Tiffany Midge

- Spring Valley Reservoir by Tiffany Midge

- Villain by Samantha Grenrock

- Extra by Jennie Neighbors

- Punch Bowl Hike Meditation by Scott Starbuck

- Full-Day Tour of Chernobyl by Vernita Hall

- Oregon by Bonnie Bishop

- The Lumberjack by William Stratton

- Life's Work by Julia Shipley

- Old Game by Karen Neuberg

- Aquarium by Amy Collier

- The Long Tom by Dov Weinman

- What Had Killed Her by Sydney Doyle

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

Kaddish in the Anthropocene Era

by Leah Korican

Leah lives and creates in Oakland, California, near the Temescal Creek watershed.

Each day with brittle tongue

even in our grief

we praise the bounty of being:

bowing, nodding, eyes closed.

How should I know

what comes after saying Kaddish?

Aren’t we always answering a question

by asking a question?

I always expect flames and plagues.

You know that Ashkenazi,

child-of-Holocaust-children anxiety?

Now 97 percent of scientists agree with me.

I see the neighborhood burning

and the smoke choking the bay,

hanging heavier than fog,

releasing its carbon into the atmosphere.

I read about the moose

dying all over North America,

killed by thousands of itchy ticks.

Terrible way to go.

The moose is not intimidated by bears,

and their size makes everyone feel small

except the ticks, who feel like a moose

is a crowded buffet.

shines dull white;

ghost moose wanders

in the dark woods till it falls.

I could say Kaddish all day for all the creatures

going extinct or threatened or vanishing.

That, along with all those Starbucks,

is a hallmark of our age.

I click links to send petitions

and share the ghost moose story on Facebook

above the cake fail and below the obit

for a famous rocker.

Should I praise the glory of it all?

Feel acceptance and peace?

Or should it be anger

like a prophet in the temple

smashing things, yelling, gesturing,

wailing, crying, tearing clothes?

What is the proper response

to the news of the death of the North American Moose?

We don’t miss the ancient predators.

We exterminated the dire wolf

and sabre tooth tiger.

Would you want one for a neighbor?

Still once the food chain

is tangled and twisted

and broken, it’s going to get ugly:

roast rat, ticks on toast.

What are the proper words

to pray, bows and bends to make

on this day

with this news?

Do we just keep saying

these tuneless words of praise,

this ageless plea for peace,

a question

we can’t help answering

with a question?

© Leah Korican

Respiring

by Gail Rudd Entrekin

Gail lives amid the Coastal Range east of San Francisco Bay in the San Pablo Bay watershed just above San Pablo Creek on lands of the Chocheno and Karkin Ohlone people.

The planet moves ponderously, turning me

into the sun my body craves, opens to receive

its heat. I breathe in air that’s passed perhaps

through the lungs of a neighbor’s dog,

the postman, the Vietnamese women at the nail salon

who breathe these atoms in and out. Everyone

who’s ever lived has taken in, used up, exhaled

reconfigured the particles that make this air.

I fill my lungs, take what I breathe into my blood,

sigh out the other parts for the maple tree,

sycamore, rhododendron, who wait

for my rejected molecules, green up, flower

or color or seed, and blow back the parts

I need.

© Gail Rudd Entrekin

Animals in the Yard

by John P. Kristofco

John lives in the Lake Erie watershed, Central Basin, about ten miles east of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River.

as if we were Saint Francis,

we crouch down on one knee to summon them,

think they’ll come for comfort, love,

share some common soul----

in twilight backyard after dinner,

Eden with no tree;

but they stay back, watch

as quiet fills the space,

and we sense it isn’t Disney after all:

they stare as if they’ve seen the films:

Orwell’s, Hitchcock’s,

that business at the beach,

and they move with DNA resentment

for “dominion” and “subdue;”

the breeze grows chill;

we scan the yard, the sky,

arise uneasy as an alley walk at midnight,

and back into the kitchen

where we watch them

from the window in the place

they knew we came from

all along

© John P. Kristofco

Dear Future

Preliminary treatment uses screens or grinders to capture or macerate solids such as wood, Q-tips, and dead alligators so they don’t muck up the works further down the line.

—Dave Praeger

by Joan Baranow

Joan grew up in New England and rural New York in the midst of dairy farms and deciduous woodland. Her arrival in California coincided with several years of heavy rainfall—a sweet welcome to this usually arid climate.

We tried, really. When ooze gooped up the ocean

we invented suction to separate plastic from salt,

but too many dolphins got torn apart in the process

and you know how we felt about dolphins.

After that Congress canceled the Internet

and put the country in reverse.

No one could remember bologna sandwiches

or Simon Says anymore anyway.

The Super Bowl, however, remained

high octane. We hosted parking lot brawls

and instantaneous T-shirts.

Not so Women’s Lib weeping at the seams.

It all depends on what we thought was real.

Sidewalk cracks were avoided.

As were robo-calls. Even the thought

of lab animals patched up for the night.

We could never agree on which death

was best for the country. On whose terms.

Clearly humans had become immune to irony.

We engineered nets to catch the suicides,

then legislated assisting them to death.

Please know these were the good days

before you replaced us. We thought

nothing of trading hearts among species,

injecting toxins to effect a cure, passing

the body through enormous magnets to map

the damaged gut.

It was good times. It was plenty

of packaged beef, bubble wrap, clam shell,

call waiting, deodorant, non-stop flights,

zero prime rate, Safe Zone training, and

antimicrobial copper-alloy surfaces

too slick to stick to, though

measles made a late comeback at Disneyland.

It was easy to get sweet on nature

with a bottle of amoxicillin in the fridge.

We stripped off the lead paint and installed seat belts.

We figured death happened to other people

for the best reasons. The worst, they say,

was picking Q-tips by hand out of

the sewer grates. That was 10% of the job.

The rest was shoveling sludge from city drains.

As I said, despite being a bickering, tormented lot,

we tried. We really did.

© Joan Baranow

Bolinas Lagoon

by CB Follett

CB lives in the Mt. Tamalpias watershed in Marin County, CA.

Out of marsh grass

seemingly empty

the white shawls

rise into air

and fly.

© CB Follett

One Bird Falling

by CB Follett

CB lives in the Mt. Tamalpias watershed in Marin County, CA.

A bird falls,

spinning in widening circles,

like a spiral losing its tension,

or a pebble dropped in a pond.

The bird is already lost,

some distant shot, or a falcon

pierced then let it slip, and it falls

pulling the sky after it.

Like egg shells collecting again

in a film run backwards.

The waters of the pond reflect its coming.

The waters of the pond open

like a passage and welcome the bird in.

Not a bird now, but a flutter

of loosened feathers, a pirouette

adrift on a pewter eye.

No one can put this bird back together.

No one can uncrack the egg

of this world. The heart

flutters against itself. The bird,

which has fallen into the water

has sunk from sight, the feathers have drifted

and spilled over the distant weir.

The rift closes over itself

and the surface, again, is smooth.

© CB Follett

The Death of Rachel Carson--April 14, 1964

The battle of living things against cancer began so long ago that its origin is lost in time. ~~Rachel Carson

by Donelle Dreese

Donelle lives in the Little Miami River watershed in Cincinnati, Ohio.

It had spread to her liver.

She never read the last letter

from Dorothy, the one that said--

I have come to a great sense of peace about you.

She said for all at last return to the sea.

Then death came whale-bursting

into her life, metastasizing

stirring its cellular gravel.

Denial is a disorderly thief

and resistance turns water to lead

so she let the thing flow through her

plunged her tired arm into the mud

felt the cool, thick mercy

against her skin, waited for the clay pack

to reclaim her fingerprints

until pain became impossible.

© Donelle Dreese

Night Caller

by Tiffany Midge

Tiffany lives in Moscow, Idaho, which lies on the eastern edge of the Palouse region of north central Idaho in the Columbia River Plateau, homelands of the Nimiipuu-- the Nez Perce.

The mollusk inching toward my door,

its body a broad wet muscle of rain and ascent

reminds me how all things are possible,

just as the rain foretells certainty

in a language of unquestionable voice.

I hear the night break, the moon

tossing back her hair. I hear the hum

of contentment shuddering in the grass.

The mollusk seeks direction, drinks

in the door’s pool of light, charts

a course for warmth, its horns

pivots of radar, exclamation points,

exquisite attachments puzzling out the smell

of water and storms. In the last twenty-four hours

there’ve been sloughs of visitors to this porch:

half-drowned spiders, stink bugs, furious horse-flies.

We’ve discarded them tenderly, others

mercifully tended and killed—unnamed shadows,

unmarked graves, wings and songs put to rest,

lunacies of want laid down. You turn in sleep,

then wake and tell me about tropical weddings

and masked brides, guests who only speak

the warbled tongue of sparrows, and fall back again—

dreaming your night stories, hosting the night visits,

each with its own small creature,

each with its own grand light.

First published in Drunken Boat and appears in author’s collection, The Woman Wh0 Married a Bear.

© Tiffany Midge

Spring Valley Reservoir

by Tiffany Midge

Tiffany lives in Moscow, Idaho, which lies on the eastern edge of the Palouse region of north central Idaho in the Columbia River Plateau, homelands of the Nimiipuu-- the Nez Perce.

Some things are necessary, the pheasant

for instance, her call claimed first in the chest,

an elegant not wholly unpleasant

thrum as if a small being has made a nest

below your ribs, then strikes her way out.

Or the heron who wreathes the water

dragging along a veil of mist like white-

lace meteors along the reservoir

banks. We need the osprey, her acrobatic

plummets for bluegill, her aerial craft,

the way we need air, water, light. The creek

runoff pitches into a green prayer mat

of marsh amazed by its own silk body.

We live on this: the wings, the rhapsody.

First published in Yellow Medicine Review and appears in the author’s collection, The Woman Who Married a Bear.

© Tiffany Midge

Villain

by Samantha Grenrock

Samantha lives in the Oklawaha watershed near Hogtown Creek and the Cabot-Koppers superfund site. The canopy is all banana spiders and Spanish moss.

Raiding nests for fun, the black and white tegu

is caught on camera, an egg larger than its head

held lightly in its jaws, then carried off

and consumed without pleasure. That third-eyelid lizard look

looks past you. Like so many things on the cusp

of unmanageable, the tegu came by ship

and made a break for it. Descendant of that first escapee

tastes the familiar subtropics with a forked tongue, pink and lolling

in its mug shot, as if to say, there will always be more of us—

necks thick like Godzilla’s, black and white markings

greenish in youth, bad attitude,

no goals. These opportunists.

Here it is again in the coarse pelt of St. Augustine grass,

jumping the fence when the invasion curve says release the trappers

in their day-glow vestments, ready the canvas bag.

© Samantha Grenrock

Extra

after Wendell Berry

by Jennie Neighbors

Jennie lives below the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Saluda River Basin, near where the Reedy River flows through Lake Conestee.

to find consolation where “the great heron feeds” --

as if the great heron feeds on air,

as if without terror

the too-late frog is caught by the keen bill

there is no consolation in wildness;

there is no wildness:

the great heron eats as it must,

and, besides, nothing is untouched,

nothing is beyond us

when we are all gone

and the universe is chemicals and laws without eyes

will it matter that there is no memory?

yet in some nowhere of the centerless expanse

a heart feels weightless

we are each this world,

a production of laws and chance,

so tell me, what is lightheartedness?

do tadpoles swim through crystalline palaces?

do birds glide through expanding air?

somewhere, someone’s heart is light

everything is extra

© Jennie Neighbors

Punch Bowl Hike Meditation

by Scott Starbuck

Scott travels between the north Oregon Coast, Columbia River Gorge, and his teaching job overlooking The Rose Creek Watershed in California.

For 30 years

I’ve talked to myself

about climate change

but now most everyone is.

When you think that long

you feel for

Nina in flower garden,

sparrow on fence.

An earlier draft of this poem appeared in San Diego Reader

© Scott Starbuck

Full-Day Tour of Chernobyl

One of the most radioactively contaminated sites in the world: the 1000 mile Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) Exclusion Zone in Ukraine, around the site of the reactor explosion of April 26, 1986.

“Found poetry” text excerpted, in order, from a tours webpage1.

by Vernita Hall

Vernita is a lifelong Philadelphia native. In her northern neighborhood of old houses and quiet streets, Kwanzan cherry trees, azaleas, and rhododendrons glorify each spring.

Low Price Guarantee!

Explore the Exclusion Zone

You are welcome to spend

maximum time inside

see an open-eye experience

Expect some changes

abandoned houses and barns

an almost fully buried village with

a kindergarten

a Red Forest

The first and worst fall-out:

the town of Pripyat

populated by 50 thousand people

before the evacuation

The fire fighters and NPP workers

badly affected by

a river of consequences

a correction point, ruins of culture

for the Prypyat youth

Ferris wheel in the amusement park

which was never open—

a disaster

After explosion: giant catfish

<Giant secret>

Tour includes radiation

and personal departure

Necessary information

(unlikely to be confirmed):

in case of

eating, drinking, and smoking in open air

touching buildings, trees, plants

eating mushrooms, berries, fruit, and nuts

in forests of the abandoned settlements

sitting on the ground

on persons there is

a 100 percent cancellation

1 “Full-Day Tour of Chernobyl and Prypiat from Kiev,” Viator, 20 Oct. 2016.

© Vernita Hall

Oregon

for Clare

by Bonnie Bishop

Bonnie lives on a 40-acre outcropping of ancient shale and limestone beds, part of the 600 year old Cambrian sedimentary Weymout Formation. This little island in the North Atlantic is connected to the mainland by a mile and a half long tombolo and is famous among geologists for its gabbro.

Down through the twilight we drove,

leaving behind the promontory,

the long view of the misty beach

punctuated by boulders big as hotels,

the lavender horizon and mottled sky,

down through deep green groves

we rode, talking about resurrection,

the kind when people we know have

stepped out of the tomb, blinking,

waving away spider webs, stepped

away from damage and despair

into the green life that seems

to have been waiting for them all along,

when an elk stepped out of the path of our car

into the coniferous, ferny-floored forest

and turned her huge beautiful head toward us

before vanishing.

© Bonnie Bishop

The Lumberjack

by William Stratton

William resides on the shores of Lake Champlain, nestled between the relatively fast-growing Adirondacks and the much more ancient Green Mountains. Hiking up through a few thousand feet of stone, water, ice and snow of those peaks, he can almost make out where the Lamoille River reaches the bay near his home.

I took trees from up on the mountain

for thirty years give or take. The trees

took my youth, my joints, and gave me money.

I couldn't spend it on anything

but the bottle and some brown then my wife

left and I tried putting my life back on

for a while but damned if I hadn't forgot how.

I knew how to fall them just right I almost

never had one hang and I could close my

eyes right before the final cut and feel with

my hands the slow tip of the big body and

know where the mainline was, waiting to

pull the big logs down to landing. I was good.

Not many left now, like there was.

I put the logs down one by one for years but

they got the better end. I might as well

have fallen out there, among friends.

I might as well have felt something snap,

felt the heat of sap on my body felt a hole

in my gut or maybe breaking an arm or leg

the last thing I remember the cold steel

in my side punching right through

maybe I could hear the saw and maybe

I could see one last time that I had

stood on my own and that I was

worth something and that somebody

wanted me to be strong and good

and I would have blotted out the sky

for one long minute as I fell as they

tried to catch me and then only

the earth could stop me hitting

the ground and yeah I pulled logs

out by the hundred over a long while

but at least they died among family.

© William Stratton

Life's Work

by Julia Shipley

Julia lives in northern Vermont, an area very much renovated by glaciers, beside the Black River in the St. Francois watershed, one of only a few in the United States which flows north.

I was nineteen, almost

twenty when the driver

gave his bully bus a break

on the brink of the Great

Outback by an anthill

taller than he, actually,

there were three termite

towers comprised of silica,

saliva and centuries of sustained

intent—a monument

to minute contributions,

and the wheezing driver on the cusp

of his retirement pension granted us

this spectacle, wanted or not,

thus some of us studied this pinnacle

of a civilization while he rolled

his cigarette, and licked it shut.

Smoke break over, Righty-O,

he stubbed his butt and steered

the bus back to the bitumen,

to finish his piecework, his portion

of the multi-stage circuit:

Darwin-Uluru-Melbourne;

twenty years along, I hereby

consecrate my witness to this

glory: how we go, how we come—

syllables accreting via saliva-ed

tongue, day upon day, rising

by the hour—our accruing crumbs.

© Julia Shipley

Old Game

by Karen Neuberg

Karen lives in the Atlantic Ocean/Long Island Sound Watershed in Brooklyn, New York, just a few blocks from the East River.

In yet-to-be hours, the remaining

children play the old game.

Milling around each other,

they jump and lumber, walk on all fours,

leap, roll, sniff, hug, flap arms,

and make assorted noises—

snorts, barks, buzzes, grunts, trumpets,

roars, low- and high-pitched cries—

until one by one, they clutch

themselves and fall.

When all are down, another child

sprinkles each with powder

said to contain ground

horn and tusk, beak and claw,

while reciting in a solemn voice

names memorized by heart:

Whale, bat, bee, tiger, falcon, bobcat,

wildcat, zebra, gray wolf, jaguar, dolphin, giraffe,

manatee, terrapin, ocelot, elephant, gorilla, polar bear,

rhinoceros, hippopotamus, orangutan.

And with each name said,

a child raises an arm.

And this is the old game the children play.

And its name is Sorrow.

© Karen Neuberg

Aquarium

by Amy Collier

Amy was born in the middle of five Great Lakes and now lives on pudding stone that is rising up at a very gradual rate.

Among a school of workers

funneling into the train

commuting to or from

a many windowed building

I think of

age eleven

the Monterey Aquarium.

I see tuna shooting through

a cylindrical display

in a liquid silver ring

above my head

and the plaques tell me

to fish it's all the same.

The bluefin's happiness

is 40 mph. We have

tricked their perception

of place and distance.

© Amy Collier

The Long Tom

by Dov Weinman

Dov lives next to the sea and in the shadow of Mt. Panamao on Biliran Island in the Philippines. Waters from the Badiang River feed the many water falls and terraced rice paddies scattered throughout the rolling hillsides.

I help slide the kayaks into murky current,

feeling more than seeing his excitement

at being able to take me out on the water.

I leave for overseas service soon, and we're

mostly quiet as we point toward red-winged

blackbirds dancing out of the reeds and

spiraling marsh wrens. We slowly move by

cattails and around sunken logs, relics of

an older forest. Listening to bird calls, our

paddles smoothly push our crafts and cause

an egret, dressed in white, to abandon its

patient hunt along the bank. A bald eagle,

enthroned on a wind-twisted snag, looks away

from the warm sun that paints our shoulders.

We leave each other to our own thoughts,

mine drift toward the future, knowing that

this place may disappear, its shady, floating

passages and overgrown banks caught by

the slow progress of a growing city. I know to

hold close these moments with him so that I may

flip through them later, like the soft pages of a

favorite novel, to remember my excited father

looking to wings flickering in the sky and

turning to see my reaction with smiling eyes.

© Dov Weinman

What Had Killed Her

by Sydney Doyle

Sydney was raised among the pines near the upper Delaware watershed but has since migrated, with the blue crabs and the blue herons, to the Jones Falls watershed in the Chesapeake Bay area.

I saw the sheen of the vulture’s black wing

before the smell of something dead

filled the car.

The bird’s hunchbacked, half-heart body bent

into the neighbor’s cat: a fat Calico

whose green eyes I’d often catch lit in headlight,

before she’d turn her pointed head.

I thought of the two children

she waited for the school bus with.

Their hands wriggled after her

black tail snaking into hyacinth.

I’d sped down this road countless times

before. I’d once seen the cat,

with a chipmunk in her mouth.

But a certain kind of creature eats the dead, like this:

white talons dipped into a ribbon of innards,

black beak cut into fur, picking at the long expired.

The yellow vulture-eye pinned

on something beyond the body.

I honked the horn,

though the cat was already dead

and gone with the taillights

of what had killed her.

© Sydney Doyle