Issue Number 50, Fall 2020

Contents

- First Rain by D. James Smith

- Red-Breasted Nuthatch by Joan Gibb Engel

- Maple by Joan Gibb Engel

- Dawn is When the Dead Breathe by William O'Connell

- Momentary Light in Momentary Time by William O'Connell

- Dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia, 1987 by Rafaella Del Bourgo

- The Inexplicable Business of Fish by Rafaella Del Bourgo

- Redwood Dharma by Laura Grace Weldon

- Why Did I Call my Pig? by Dion O'Reilly

- This Ocean by Luke Wallin

- Hunting at the End of Time by Luke Wallin

- View of Dorian from the International Space Station by Steven Croft

- Just Passing Through by Dan Jacoby

- A Poem for Roadkill by River Hall

- A Hole in the Sky by Lois Levinson

- October Cricket Posts a Personals Ad by Gene Berson

- Ghost Forests by Lauren Slaughter

- The Stag by Natalie Mulford

- The Drummer by Larry D. Thomas

- Turkeys in the Meadow by Donna J. Long

- On the Winding, Muddy Stream by Carson Colenbaugh

- Badlands by Jordan Osborne

- Sunfish by Hugh Findlay

- Saw-Whet Owl Irruption by John Kaprielian

- Natural Capital by Ruth Bradshaw

- The Naming of Brush Fires by Laura Saint Martin

- Something about Morning by Lois Marie Harrod

- Stormwatch by Thomas Mitchell

- Learning of Unsuitable Habitats by Kelly R. Samuels

- The Mending by Rhett Watts

- Bristling Senescence by Don Noel

- An Invitation to the Apple Harvest by Tanya E. E. E. Schmid

- Music and Memory by Robert Coats

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

First Rain

by D. James Smith

Smith lives in the irrigated, semi-arid desert plain of California's central valley, spending a great deal of time in the nearby foothills and the Sierra.

Soft on the roof and I wakened remembering

The storm from some years back so strong it blew

Heads off trees, sent road signs spinning

Like scimitars, then the air falling suddenly slack

Then winding up again and the rain

Twisting in silk ropes from the eaves I stood under

Staring past them into sky, trying to find one line,

To follow its travel all the way down

Until my mind was falling, too,

As if tossed from a plane, no parachute, a man diminishing,

Stunned with the gravity of things.

It began with gentle though certain flecks on my face.

The first I welcomed, though withdrew my dawn cup

When the drops went from tentative to a fat plunking

Into my coffee. Midmorning I started backing away

From the glass, watching what I could on TV, sure, then,

Something was up. Come afternoon I was considering the chances

The weather would break the back of the bad years in the Sierra

Which had killed countless trees doomed by drought beetles

Whittling their multitudinous, deep-chambered tombs.

It wasn’t exactly Biblical, though the wind, insatiate,

Was full of stories, beginnings and endings,

Which have gone their own way for ages.

When the levees near Stockton gave way

Like the slump of old shoulders, water seeking the low

Places the highway was river, and the woman

With her two babies in car seats said she wouldn’t swim out

Without them, 911 recording the last of their high singing.

There’s a wild dignity in me that wants to sing, spurred

By the violence of things trying to become themselves enormously,

Metamorphous at a cost. The newscaster on air,

Helicoptering overhead actually suggested prayer

And, you know, I mean, no matter what I think of him

Christ’s lesson in fidelity was no easy feat. My own heart

Still weakens and skips its two-step too quickly

When I don’t know what it is trying to come through

Though I go on understanding it’s a kind of chanting that drops

This side of mortality which I feel like a boxer going down

Hard, braving closely examined failure.

The daily loneliness of rising again.

It was Channel 24 or my mind sending me pictures

Of the cold river caving in the doors of houses,

Walls leaning until they slid and lay all the way over

Slowly, the roofs like doffed hats sailing away on the water

So that my thoughts, disordered, for a moment,

Caught sight of the holy seal of one upstairs,

Emily Dickinson window, and my neck twitched

When that one dark starling I glimpsed

Catapulted into that glass.

The last night it slowed, and I, then fully awake,

Beginning and true, saw the night sky drawn

And quartered as it gave way so that

From its center stars stepped out carefully to quiver.

Glancing down I saw worms struggling out

Of the old, ill-fitting clothes of soil,

From the eaves came a dove’s, Oh, Oh,

Melting open a hole in the air,

And I entered.

© D. James Smith

Red-Breasted Nuthatch

by Joan Gibb Engel

Sadly Joan died a few days before this issue went to press. Her husband asked us to use the following: "In the last weeks of her life Joan looked out each morning at the little garden of native Sonoran Desert plants that she had gathered in the rear of her adobe home in mid-town Tucson, and told her friends that seeing them not only connected her to the surrounding desert ecosystem, but brought back to life the Indiana Dunes where, following in the steps of pioneering field naturalist Henry Cowles, she learned the elements of ecological science and began to write her poetic ecological vision of the world."

Remember?

I would like to think we each remember

the way that day the pines saluted winter’s coming

with upright silent stance

that day you came, small fragment torn from nut-blue

fragrant hollows, came alone,

without your bugle-corps contingent

brave beyond good sense, harking back

to covenantal tales of unspoiled garden,

of women, men and animals with tongue in common

or it may have been that, simply striking out as heroes do,

you saw two needy creatures like yourself preparing

for the cold you knew was coming, one, the shorter,

pushing logs uphill, the other tall with acrobatic wing

cleaving them in pieces sized for burning.

The noise my husband’s chopping made!

And still you flew straight out of lowered sky,

teetered once then stood twig-legged on wheelbarrow’s

rusty rim, red-breasted feathered bomb

of consciousness, patently impatient, as if,

seeing our cottage down below, you decided

on the moment to stop in but had a hundred things

to do by sunset, and so if tea were coming,

make it quick.

How did you know I had—how did I know to have—

seeds stashed inside my blue-jeans pocket?

and the way you chose among a handful,

wiped your bill across my palm, scattering

all but one—the largest—then flew off high and open-winged,

to return the way you left and ask for more.

Sometimes I saw you knock the seed against a tree trunk,

more often you were out of sight.

We named you Presto,

marveled, grateful beyond words

for your faithful coming at a whistled call

or when you heard from somewhere, far

inside leaf-scattered woods, a screen door open.

One time the UPS man brought a package,

drove his big brown truck far as the entrance of our path.

We greeted him together, you and I, and when he said,

astonished, “Lady, you have a bird perched on your shoulder,”

I acted unaffected. “Yes, I know.”

But oh, friend Presto, how I exulted.

My husband and I departed before the winter’s fury.

The asters were still blue, sweet everlastings lasting,

the bracken all but disappeared.

And there’d been flurries, talk of heavy snow to come.

I had to do it, Presto, yet I ached to think you listened

for my whistle that next morning and mornings after

in the frigid wet,

hate to think you learned a lesson, saw up close

clear proof of feckless egoistic human love.

© Joan Gibb Engel

Maple

by Joan Gibb Engel

Sadly Joan died a few days before this issue went to press. Her husband asked us to use the following: "In the last weeks of her life Joan looked out each morning at the little garden of native Sonoran Desert plants that she had gathered in the rear of her adobe home in mid-town Tucson, and told her friends that seeing them not only connected her to the surrounding desert ecosystem, but brought back to life the Indiana Dunes where, following in the steps of pioneering field naturalist Henry Cowles, she learned the elements of ecological science and began to write her poetic ecological vision of the world."

In my presumption of powers supernal

it would have gone three years ago,

its twin poles rasped with hand saw

or pinched with steel-jawed clippers.

It shot from the edge of the cliff

too near a pair of lofty pines, disturbing

their solitary magnificence, interrupting

the scenic plane of sky and water.

Long before it hoisted those few ragged flags

that held on despite wind and spray,

I would have leveled my almighty sword

and been well pleased.

Now, in the spring of its adolescence,

I see it clustered with rust-washed leaves,

umbrella tufts on slender threads

graceful beyond understanding

(more than I would have drawn

yet enough and not too many).

© Joan Gibb Engel

Dawn is When the Dead Breathe

by William O'Connell

Bill lives in the Connecticut River Watershed between “The Great Beaver” (aka Sugarloaf Mountain) and the Hadley Range in Emily Dickinson's town.

A great blue heron cruises

suburban rooftops. It calls, hoarse,

trembling, out of key.

One child sleeps and another,

inside my lover,

breeds, divides, breathes.

We pray to the moon’s

invisible light, meld

to the physical, to the deepest recesses

of limbs and hair.

When we open our mouths

vowels form and push out,

vibrate, and sing.

We listen with our ears,

with our smallest bones.

© William O'Connell

Momentary Light in Momentary Time

by William O'Connell

Bill lives in the Connecticut River Watershed between “The Great Beaver” (aka Sugarloaf Mountain) and the Hadley Range in Emily Dickinson's town.

The limits of words and paint.

Music is unbound: a child knows this—

straining to utter

I want.

The insistent thrush each dawn

that sings its way west and north—

Wampanoag on the bluffs of the Cape

worship as the Mayflower slides in.

I let my soul down and walk awhile.

Even the rich can’t buy certainty.

First light touches my cheek

and the tip of my nose before

filling my eyes.

© William O'Connell

Dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia, 1987

by Rafaella Del Bourgo

Rafaella lives between the coastal hills and the San Francisco Bay with her husband and one spoiled cat. Along the back of their property line, a row of Italian cypresses plays host to birds and squirrels. Underneath this urban neighborhood runs Potter Creek.

In lazy circles they cruise the shallows,

heads up, hungry for the air,

and, maybe, for the sight of land.

One slides along my legs and

when I reach down to stroke her rubbery skin,

she smacks her tail like a cranky aunt

tired of company already.

A nudge behind my knees

and here is another with a fish in his mouth.

I take it gingerly, avoiding his white picket teeth

and, glad the fish is dead,

caress the animal’s warm flank,

read the billboard near the high-tide mark:

If a dolphin gives you a fish. Keep it. Returning a fish

is bad manners.

One dolphin swims to a yellow lab

standing up to his chest

in cool blue ocean.

The dolphin pushes her beak into the dog’s black nose,

rubs her face against coarse fur.

A woman on shore calls, “Magic, Magic,”

but the dog does not move.

The dolphins gather

wearing their grins,

then swim west and disappear from sight.

The dog and I stare after them,

the fish, a cold and slippery weight

in my hand.

© Rafaella Del Bourgo

The Inexplicable Business of Fish

by Rafaella Del Bourgo

Rafaella lives between the coastal hills and the San Francisco Bay with her husband and one spoiled cat. Along the back of their property line, a row of Italian cypresses plays host to birds and squirrels. Underneath this urban neighborhood runs Potter Creek.

Hiking the train tracks

between Bangkok and Chiang Mai,

I observe

a walking catfish,

eighteen inches long.

Not scalloped and iridescent

but black, dull;

his skin absorbs the light.

Crawling out of his rice paddy

of green wands

and silver water,

he propels himself on fins

ribbed and stout,

flat as the full moon

in the morning sky.

Dust coats his belly

and throat

as he muscles slowly

up the incline,

twenty feet

to the tracks,

hauls himself

over one rail

then another.

He lifts his head

to eat the air

one last time,

then, six pulls and a slide,

he spills into the rice paddy

on the other side

and disappears.

I shift my pack,

continue north

toward emerald trees,

pewter clouds.

A light rain

embroiders my hair.

© Rafaella Del Bourgo

Redwood Dharma

by Laura Grace Weldon

Laura lives on a small Ohio farm where rain rushes toward Little Sweetly Creek, enters the Black River, merges with Lake Erie, and then the St. Laurence River on it its way to becoming the ocean.

Redwood trees have lived on Earth

for over 240 million years.

Homo sapiens, about 200 thousand.

Despite massive size,

old growth redwood

root systems are shallow.

Trees reach 350 feet tall

yet don’t topple in the strongest winds.

Each one’s roots interlace

with its neighbors’ roots,

creating a vast network of support

unseen on the surface.

They hold on for a thousand,

two thousand years, maybe more,

all the while showing us

how to grow up.

First published by The MOON Magazine.

© Laura Grace Weldon

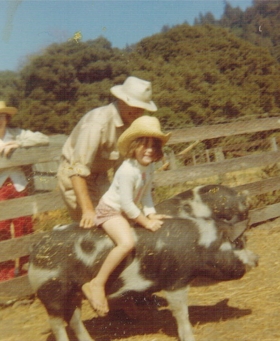

Why Did I Call my Pig?

by Dion O'Reilly

Dion lives in the Soquel Creek watershed on a stream-cut terrace covered with a thin mantle of alluvium on a ten-acre triangular plot between Soquel Creek and its tributary, Love Creek.

I watched my mother call her,

I watched my sister too.

My father chased her.

They tried to round her up,

but my piebald oinker was quick,

her squeals greasing the air.

She knew the jig was up,

ran to the farthest corner, down

by the creek and the steep ravine,

hid in the shadows under oak trees,

rooting prickled leaves and acorns

with her wet ringed snout.

My huge baby, companion

on aimless teenage days

when I balanced on the fencepost, listening

to her belly-deep rumble,

scratched with a stick her itchy,

thick-skinned back.

It wasn’t for the sausage or ham,

the pork chops, or the slab kind

of bacon you couldn’t find in stores.

The butcher with a rifle,

stood impatient by his Chevy truck

its hook and chain ready

to haul the limp sow up,

to scrape the skin and slice the stomach

in a thin red line, the bowels spilling

glazy as moonstones.

Forgive me. To show off my small power,

I called her— the one she loved—

and she came running.

Previously published in the author's collection Ghost Dogs.

© Dion O'Reilly

This Ocean

by Luke Wallin

Luke lives in the Sakonnet River watershed basin near the Atlantic Ocean on a stream that flows north.

Now rough sea and storming sky

drive the sunburned families off

Remember when the wind turned cold

and the sand was hot beneath our feet

Long time now since you’ve come down

to watch the seagulls kite the wind

to feel this wide and private sky

this ocean swallowing words

© Luke Wallin

Hunting at the End of Time

by Luke Wallin

Luke lives in the Sakonnet River watershed basin near the Atlantic Ocean on a stream that flows north.

Cypress Light by Luke Wallin

1952

In the beginning was the woods, and my father, and our first squirrel-hunting journey away from town with its noise and secrets. That fall was dry, the leaves crisp and crunchy, the hickory tops yellow and full. I remember the day transforming nine-year-old me, setting me on the path of hunting, of seeking wild animals in the tall trees, in shady thickets, along cypress and switchcane creeks. These squirrels were nothing like the boring ones in town. Somehow these were mythic, elusive, and presumably delicious. I learned the beauty of the single crack of my father’s .22 rifle across the hush of the afternoon, and of the fox squirrel falling slowly from a great height to land with a thud in the dry lake bed. I remember our long search, the emptiness and guilt, and my father’s words: keep looking, keep looking. I remember the pride of ownership in our land, and the thrill of trespassing 50 yards onto our neighbor’s, to search for the squirrel. In a single afternoon I experienced passages from town to wilderness, and from landlord to poacher.

1957

My partners Dennis and James and I lived for the purity of those woods, where all creatures existed in their life cycles, where massive trees suggested Edenic wilderness, and where God seemed to brood as he might have done in the days of Abraham or Moses.

We loved my blue-green F-100 Ford pickup truck and our mad drives down Old Macon Road, sliding through curves in the gravel, heading for the clean and natural and mysterious and unknown deeps. We were bound for the yellow-antlered bucks, the bobcats quiet as shadows, the marsh lake stirring under the moon with river bounty—bullfrogs and shellcrackers, catfish and gars, cottonmouths and terrapins. We were teenage boys with guns, our heads full of bible stories, our eyes open for whatever creature might appear next. Perhaps it would be a giant rattlesnake coiled on the sandy trail, or a red-eyed whip-poor-will in the glare of a flashlight, or a woodcock diving in the last of dusk, landing in a plum thicket to speak like a confident kazoo. All the living world was equal in revelation. We did a lot of shooting with great joy.

1973

Leaving from my Hoboken basement, I boarded a plane with my Yankee friend Tom, and as we flew south I continued the stream of stories, teaching him to hunt deer. The next day he stood in the morning fog of the Three Buck Woods, listened to a single twig snap, and caught a flash of movement 80 yards away. The buck slipped between cypresses and when his eyes passed behind a swollen trunk Tom raised his rife and placed the crosshairs on the alley beyond the tree. He exhaled and did not breathe as the buck moved into his sight pattern; Tom said he could hear my voice in his head, whispering each step. He killed the deer and the hook was set. Tom would come with me every year after that, leaving the population-exploding world, and traveling toward 1840 and Jeremiah Johnson. We exchanged the valley of ashes for the green breast of the new world.

1987

All year long Tom and I dream of our hunting week. We identify crucial elements of the hunt: camaraderie, thrill of the chase, ritual sacrifice, and communion with nature. Within these categories we place friendship, knowledge of the land and the game, moderation and fair chase, a careful shot, tending the meat, and honoring the slain animal through the cooking and feasting. We field dress our deer, and pack out the meat, bearing its weight on our shoulders like a penance or duty that redeems the taking of life. Buried in all this analysis is the moment of the kill. In our club, we try to subsume the killing itself, contextualize it; but, it is the love that dare not speak its name.

Like my partners from childhood, Tom and I swear we will never hunt anywhere else. My friends and I live all year in interior lives of this hunt, both sleeping and waking dreams of this forest, breathing a cult of hardwood landscape, imagining cavern walls in prehistoric oak, lit by the worship of large antlers.

1990

Hunting has changed. Those who can afford it bulldoze trees and plant row crops of clover and wheat for the deer. At the edge of such fields, plywood boxes preside on stilts, or hang in trees. My woods neighbor has transformed his 2000 acres into a mosaic of plantings and shooting houses.

The farmers have brought ancient hunting into the present time of industrial agriculture. We cling to the old ways, to oak bottoms, to caney sloughs, and to honeysuckled creeks that channel deer. We work hard at our half-conscious historical reenactment, atavistic time travel, creative suspension of disbelief. The farmers’ shots from their shooting houses are long and surgical, felling bucks they can barely see. Our shots are close and exciting.

1996

The wealthy neighbor, obsessed with antlers, organizes people up and down river to cooperate in a Big Buck Program. One can have lots of deer, or deer with impressive antlers. It seems there is not enough food for both. The lord of this manor reserves to himself the largest bucks, taken with a rifle designed for Africa.

2006

The big buck program is working, and now we watch beautiful eight point bucks all the time. These deer would have been trophies in the old days, but we’re letting them pass. There’s so much pleasure in this. Occasionally we take a buck that, to us, seems magnificent. Our neighbor has four months a year to hunt, with his towers, and binoculars, and his illegal bait crops. He knows each deer like his own dog, or his cow. His mounted heads drip extra points like candle wax. Tom says these trophies seem antler pornography. Visit the covers of hunting magazines, and you’ll see.

2009

After a long political struggle, Mississippi has legalized feeding the deer, and the hunters have leapt in. Feeders look like little wooden mangers, with roofs for rain. Owners fill them with corn. They are pouring big money into this to compete with their rivals across the fences, across land lines. Many of them feel they “own every damn deer in the woods,” and they are determined to suck “their” deer across property lines. This makes last year’s nightmare—crops planted as bait—seem almost natural. Those great fields of clover and wheat dedicated to the deer now seem the old lost “normal.”

Deer are hanging around tame and sheep-like, at the feeders of my neighbors. The power of the mating rut, to bring shy monsters out of hiding, to make them careless in chasing the does, has been neutralized. When 30 does are living within 100 yards of a feeder, where you think the bucks will be?

Just as bucks are losing their skills and their wild souls, so are hunters. I watch big-screen TV with a young friend in his cabin and realize his default setting is a hunting channel. His favorite show features a Texas deer ranch. The program highlights enormous antlers of living bucks, shown from shooting towers above the chaparral. After this tease the viewer is presented with special sacks of feed: "18% protein!" This ranch sells the food that nourishes the antlers just outside our cabin.

I try once again to explain our feelings to my friend, but he’s a man who understands his time, and he chuckles. He refers to Tom and me as "buffalo" because we don't adapt! He also says, "The point of feeders is not to kill deer, but to have some deer." I guess he’s right. But I ask myself, when you sit in a shooting house and watch a deer eating from a feeder, what exactly are you doing? Do you want a feedlot buck?

Tom seems on the brink of quitting hunting, after all these decades, though he has agreed to try it "one more season." I’m thinking of adding a single, corrupt, evil, demon feeder in the middle of our big pines, midway between my neighbors. I hope to spread the bucks more evenly, and yet protect our illusion of being Jeremiah Johnson in the trees. Hunting has always meant, from my initiation with my father and that squirrel when I was nine years old, the difference between the corrupt time of town and history, and the time of wilderness. Here I could experience life cycles (the time of ecology), biblical mystery (the time of Abraham), the initial touch of Europeans on American shores (the green breast of the new world), and the time of mountain men (as played by Robert Redford).

But those cultural times are gone. In the presence of feeders those experiences are no longer available to imagination and memory. Nothing has changed, really, in my fifty-plus years of hunting, except that my dreams have been unmasked as dreams. My life of hunting and managing my club has been an exercise in historic preservation, of directing reenactments on a leafy stage.

I just wish we still had wild bucks. I would give anything to go back into the old Three Buck Woods, our 1840, with my friends and hunt again. We hunt, but only in the industrial and televised present, in which we feel acutely the loss of historic presence. We are hunting at the end of time.

Previously published in the Louisville Review.

© Luke Wallin

View of Dorian from the International Space Station

by Steven Croft

Steven lives on a barrier island off the coast of Georgia at the southern edge of the Altamaha River estuary on a property with virgin pines, live oaks, magnolias, and palm trees, all home to various species of very vocal birds and mostly furtive animals.

Wide veil of buzz saw blade light

as beauty, cottony spool of chaos,

looking down from weightlessness

through an unblinking eye

Into the unbearable weight of being

human when the sky grows like a god,

vomits raging venom as winds

cutting the sea into madness

Unraveling any landscape into a mise

en scene for disaster journalism:

stripped trees, entire towns

scattered, flattened

To trash dumps complete with circling,

scavenging gulls, an underbelly

of grief, searing pain of loss, lives

altered forever

But from heaven's vantage this floating

spiral quiet as a pearl in meditation

this porcelain symmetry over a sweep

of blue earth

© Steven Croft

Just Passing Through

by Dan Jacoby

Dan's family has lived in Macoupin County, Illinois, for about 165 years. Western Mound has Bear, Lick, Hodges, and Solomon creeks emptying into Macoupin Creek which flows into the Illinois River and eventually into the Mississippi River just above Alton.

walking this old timber

among the grandsons of great oaks and hickory

deep in creek and river bottoms

or high on glacier formed bluffs

I am struck by the fact

that at least ten generations before me

traced these same well-worn hills

wondering at the quiet of these listening trees,

even in high wind and rolling storm,

a silence that rivals the holiest of places

silence broken only by a falling limb,

rustling of the grey brown leaves,

singular call of a jay or disturbed crow

I am aware also of the unforgiving harshness

fallen-in farmhouses and rotting fence posts,

abandoned wells with now undrinkable water

stark metaphors of long dead men’s dreams.

my ancestors found hope here

migrating from famine, oppression, and war

their graves, generations of them, are witness to that

arranged in neat rows in manicured or abandoned cemeteries

before them, a more ancient mississippian people,

hunted, farmed, gathered, and carved out lives

their graves still evident, if one knows where to look

and I, like all, am just passing through

in the end these bluffs, creek bottoms, and fields

will all survive me, survive us all.

© Dan Jacoby

A Poem for Roadkill

by River Hall

River lives beside a seasonal creek upon a solitary ridge of ancient land, which has been slowly carved away by the mighty Snoqualmie River to the east and Patterson Creek to the west. She acknowledges the Snoqualmie People (the People of the Moon) who have lived, hunted, and fished here as long as the earth and rivers remember.

What if we pulled over,

got close enough to feel the death-rattle

shake the air against our skin?

Offered regret for getting in the way

with our roads, our tires, our glass?

What if we didn’t abandon them

to the cement until there was nothing

but a dark stain, a rope of hide, a splintered bone?

What if we cupped the dwindling warmth

of the struck bird?

Held it long enough that it cooled in our hands,

shed tears onto the feathers of bent throat and broken wing?

What if we took them to the woods,

an offering given over in kinship with maggot and crow?

What if we took the time to give them to the soil,

death greening life for future living?

What if broken raccoon, stilled possum and lagging deer fawn

were adorned with roadside flowers and grieved?

Piled high by passersby with the dandelion, hawksbeard, red clover

—the beautiful weeds.

Previously appeared in Tinderbox Poetry Journal.

© River Hall

A Hole in the Sky

The disappearance of 2.9 billion birds over the past nearly 50 years

was reported today in the journal Science...

The New York Times, 19 September 2019

by Lois Levinson

Lois lives at 5,600 feet at the western edge of the Great Plains and in view of the front range of the Rocky Mountains. She loves to wander in riparian and montane habitats in search of birds.

How many days would it take

for three billion birds to pass overhead,

an unending procession on a flight to oblivion?

While we were busy

making a living,

making dinner,

making a point,

we squandered our inheritance of birds.

John James Audubon saw passenger pigeons

in the millions, flocks passing for days,

blotting out the sun, like an eclipse.

But we know how that story ends.

Do you remember, when we were children,

watching long formations of birds traverse the sky?

Red-winged blackbirds, song sparrows, blue jays –

we couldn't imagine they'd ever disappear.

We cut down their nest trees,

paved over their food supply,

planted flowers of no use to them.

Did we think they'd adapt?

Three billion birds vanished on our watch,

leaving an enormous hole in the sky.

One in four gone,

like canaries of the coming collapse.

© Lois Levinson

October Cricket Posts a Personals Ad

by Gene Berson

Gene lives in the northern California foothills in the Yuba River watershed. Everyone goes to the river. Like a temple, with its falls its rapids its green pools, it seems to restore everyone in a personal way. We feel our kinship through it.

I saw you at the kitchen window

listening to the space between us.

Forgive my forlorn sound, a single cricket,

at this time of year—

but this is our only opportunity.

I know you hear me

there are so few of us now.

In August there were too many of us

you couldn’t hear me.

We sizzled like a field on fire

waves within waves every voice

conjuring for a listener.

The solitude we feel now, the few of us

still singing

has a stranger allure. Our songs

no longer overwhelm the quiet.

They are as much listening as singing.

Blades of the raven scissor the air.

Schubert, who heard only five percent

of his work performed,

would understand

this silence

we listen into.

Come outside

my legs sing

feel the hair on your arms rise and lean

following the wind following

my veins’ violins into late fall ravines

where the mist doesn’t move.

Those who sing in October

sing to enliven your cold cheek,

evoke a frosty plume, a gasp . . .

answer me

we stand within a terrible pause

my brethren are dead

disappearing beyond memory

glaciers so fragile a cricket

cracks them loose with his song.

This call spans space between species.

Lets enkindle between us

what we’re afraid to hope for. Let’s sing

until stars shake

a raiment over this temporary

immensity.

Call me

however you can.

I will hear you.

© Gene Berson

Ghost Forests

“As sea levels rise so do ghost forests.”

~The New York Times

by Lauren Slaughter

Lauren lives at the southern terminus of the Appalachian Mountains. She washes her rust-red soles—stained by the iron ore dust of the Red Mountain Formation—in the headwaters of the Cahaba River.

Like bare hands

reaching

from below

the grave, these

once-magnificent

woods. Roots

that pulled

from this earth

are choked now

with salt water,

waters meant

for a life

of fish not

sunken seeds

and drowned

burrows. Cold

may no longer

come to this place

and yet the spine

shivers

to see branches

that could have

blessed shade

upon your

very own children

seem to keep reaching

for some

right word

in some right

language

human ears

can hear.

Listen. This

is the silence

of loss. Air

does not whisper

through leaves.

Air that touches

nothing

has nothing

to say.

© Lauren Slaughter

The Stag

by Natalie Mulford

Natalie lives near the hills of Wildcat Canyon along with the oaks, foxes, and owls. She has yet to see a wildcat in the canyon but did find a frog in her dining room recently during a rain storm.

Eight a.m., a Tuesday.

As I come around the rush hour curve

where the freeways snake together

southbound waves slip below the snarl

and the marsh out on the right

sparkles effervescent sunlight.

Two Mack trucks box my silver compact,

threaten my hold steady,

steel against the steering wheel.

There he is

splayed out along the highway

sapling legs tangled in the guard rail,

his long suede belly exposed like a tan canvas

resplendent and fine even in this undignified state,

regal enough for the coat of any king.

The sharp branches of his points hang low,

antlers cocked against the asphalt.

He must have been looking for water, my husband says.

That moment

when he sprang from the hillside,

this young buck gunning for his life,

he crested, mid-flight.

arcing toward hope,

just four short lanes to wish over.

The Bay.

It rippled, glinting, called to him,

like so many morning stars.

© Natalie Mulford

The Drummer

by Larry D. Thomas

Larry resides in the Chihuahuan Desert, where he enjoys a magnificent view of the 9,000-foot Organ Mountains. Three miles to the east of his home lies the Rio Grande River flowing to its destination of the Gulf of Mexico 900 miles away.

Even in my dreams,

I hear the moonstruck

goddess of the Gulf,

pounding her membrane

of sharkskin, her drumbeat

marching leeward

toward my travel trailer

gleaming in moonglow

like a strange, metallic shrine.

I picture her submerged,

featureless face staring

everywhere, matted

with tentacles, her boneless

body advancing, receding,

cursed with the permanence

of motion, a mass of brine

and liquid cells graced

inside and out with shells,

trinkets of serrated teeth

dead and alive, a goddess

of nothing but mouth

and motion, devouring land,

her drumbeat throbbing

in the bloody, calamitous

muscle of my heart.

© Larry D. Thomas

Turkeys in the Meadow

by Donna J. Long

Donna grew up a few miles from the world's most beautiful beaches on the Gulf Coast of Florida but rode horses in orange groves instead. She now lives surrounded by spruce and beech in north central West Virginia

Heads bald, beards limp, tails slung

low and formal as statesmen, they move

like politicians in grave cadence

across the hill, listening for crickets

kicked up in shorn grass. Demeanor

severe, the Orrin Hatch of the oversized

bird world, closer to dinosaur than dove

or hawk, Toms lumber along in doles,

skulls bobbing, pendulous snoods

reddening after hens or soothing

to blue at night after improbable

flight to roost in trees with posse,

gang, crop or raffle—monikers

that do not muster Franklin’s fondness

for turkey vanity (said Ben in a letter

to his daughter, the gobbler’s virtue

proved the eagle’s bad moral character).

Today, we name “turkey” the jerk, jackass,

and idiot in need of insult, but these

pedants of small prey, portly wattles asway,

fan out across our pasture like a search

party, iridescent of feather, a lustrous

enterprise, an expedition underway.

© Donna J. Long

On the Winding, Muddy Stream

by Carson Colenbaugh

Carson grew up on the banks of Proctor Creek and is currently a horticulture student in the watershed of the Savannah River. His favorite plant is striped wintergreen, which he searches for beneath the leaf litter.

Put-In

You don’t get over your first dead dog.

A black back and a white belly,

it wasn’t rotting or festering

but I didn’t know it was there

and its teeth were still flashing

in the everlasting snarl

and the stench came and filtered my way

and I knew it was dead.

Bridge I

We meet the tenants of the plains,

the bobcat running down the game trails,

wood ducks in the early morning, flapping,

beavers still in the mud and the grass.

A kingfisher on the fallen branches.

A cardinal in the bush.

Bridge II

We recite stuff we know by heart

and laugh and forget to paddle

and drift in the current, twirling in the eddies

enveloped in the sweet rot of the river,

the musty and alive smell

of algae and fish eggs and sediment

and oil spills, and freshwater.

Bridge III

We shoot through the pylons of a mighty bridge

and get sent flyin’ through the water.

New explorers in an old land,

old men under a young sun.

Bridges IV-VII

Nothing but the everlasting flow of water

west

in the rain and the downpour,

the cloudy afternoon.

Take-Out

Rice and vegetables in the town.

The smell of the rain, and the fire, and the river,

but always of the river.

Previously published in the author’s collection, Tell Those to Come.

© Carson Colenbaugh

Badlands

by Jordan Osborne

Jordan Osborne lives nestled between the Front Range prairie and Long's Peak in Colorado.

i’ve never met badlands i didn’t love,

body a forest on fire—

where ravens tilt towards the sky only

to find themselves digging through

dumpsters for discarded bread.

forested body in the fire,

and there are feral kinds of incantations

making lanterns out of empty

blue air. empty blue

body like a forest on fire

and closeted—

shut like the ivory tusk that makes

a music box into sadness,

into a body on fire, a forest

that speaks in the dark.

those are crickets and they are crying.

and the badlands all blue

with spruces on fire—

a canyon that was born ragged

and awake from the bluelit river

regrets its red, its memory of blood

staining and burning its history of body.

the rock used to mumble its oaths

and now it screams.

and the badlands all blue with empty

night skies—i couldn’t love

the bobolink well enough when i first

heard its body heaving a song like fire

but i’ve forgotten the sound, now that it’s gone

and can’t imagine me without

© Jordan Osborne

Sunfish

by Hugh Findlay

36 lat. -79 long., Planet Earth.

All at once they swim

Leaves of fish on waving trees,

Turning in sunlight

© Hugh Findlay

Saw-Whet Owl Irruption

by John Kaprielian

John lives in the Croton watershed, equidistant from the Hudson River and the Great Swamp, at a lively spot on the Atlantic flyway.

The cupboard is bare

boreal forest floor

barren of voles and mice

for lack of seeds

natural cycle or

climate chaos

it neither knows nor

cares just

perches hungry

in the fir and spruce

Something old and

deep in its brain

tugs southward

or perhaps it

just follows scarce prey

to more verdant fields

in unknown lands

To us it is

a magical invasion

huge golden disks

stare down

from tiny bodies

almost perfectly hidden

and we gawk back

with telescopic eyes

and pointing fingers

But they are hungry

disoriented

fearful

in this new land

of unnatural shapes

and invisible walls

Refugees in the

land of plenty

Previously published at Naturewriting.com

© John Kaprielian

Natural Capital

by Ruth Bradshaw

Ruth grew up within sight of the River Mersey and now lives on the hill above Deptford Creek close to remnants of the Great North Wood.

The grey heron stands hunched and motionless on the riverbank barely 30 feet away. It is so still that I almost mistake it for one of the replicas people use to deter real herons from taking fish from garden ponds. The autumn sunshine illuminates the mosaic of fallen leaves beneath my feet and makes patterns on the slow-moving water as the wind gently sways the surrounding willow and elder trees. Pausing a while to observe the soft colours and unhurried movements of this scene, I am so intent on watching the heron that I nearly miss its flashier neighbour. The first appearance is more sensed than seen, as though the sudden bright streak of movement has created a change in the atmosphere. Alert for it now, I keep my eyes on the river and the overhanging branches a few feet above the water and a minute later I catch the return flight – a flash of turquoise and a whirr of wings as the kingfisher heads back up river – “like a streamer from your own eye’s iris” as Alice Oswald describes it in Dart.

Kingfishers are not easy to spot but what makes this sighting even more surprising is that I am not out in the countryside or even somewhere in the edgelands but just 15 minutes’ walk from my home in south-east London, about five miles from the city centre. Shortly before the River Ravensbourne completes its 11 mile journey to the Thames in the tidal reaches of Deptford Creek it runs along the edge of tiny Brookmill Park with river and park squeezed between an A road and the Docklands Light Railway. This area appears on Google maps as a narrow slither of green and blue surrounded by the grey and white of the rail lines and residential streets that dominate online mapping of this part of Inner London.

That evening I look up information about urban kingfishers online and find photos of them perched on pieces of scrap metal and flying past the dumped shopping trolleys that are a feature of so many urban waterways. Pollution control and a reduction in industrial activity means many city rivers are now significantly cleaner than they were a generation or two ago but kingfishers’ adaption to city life is also being given a helping hand by local authorities who drill holes in concrete walls to create nesting spaces for them.

The kingfisher by the Ravensbourne comes to mind again a couple of months later when I’m reading the Government’s 25 Year Plan for the Environment. One concept that features strongly in the plan is natural capital - the idea of thinking of natural resources, such as air, land, water, species and minerals, in terms of the value they provide to humans either directly or indirectly. In theory, if we can place a value on these “natural assets” then they can be incorporated into the assessment of a project in the same way as the other associated costs and benefits, a process known as natural capital accounting. Thus, if it was proposed that an area of woodland should be destroyed to make way for a new road, the loss of the benefits provided by the woodland such as carbon storage and recreational opportunities could be balanced against the potential benefits of the new road, such as reduced journey times.

I have worked in environmental policy for many years so I understand why natural capital is an attractive idea for many environmentalists. It provides new opportunities to make the case for conserving certain aspects of nature but it is not without its problems. What about those natural resources, such as inspiring landscapes and rare species, which it may be difficult, or even impossible, to value but which are nevertheless hugely important to us? How do we ensure we don’t undervalue those natural resources whose role we do not yet fully understand? Is it even appropriate to think of the value of individual natural resources separately in this way? Seeing the kingfisher in Brookmill Park lifted my spirits that Sunday afternoon but such an intangible benefit could never be reflected in a value on a balance sheet.

I am still contemplating the merits of natural capital when I go on a fungi walk a few days later. David, who is leading the walk, has spent years learning about fungi and clearly has huge enthusiasm for the subject but when someone asks him who he works for it turns out he makes his living in financial services and only uses his expertise on a voluntary basis. He’s not a professional mycologist as there are so few paid roles for fungi experts. Would this change if there was a greater emphasis on natural capital? Fungi have huge importance in ecology due to their symbiotic relationship with trees and their role in recycling other organisms but that role seems to be very under-valued, perhaps because it is often associated with death and decay rather than regeneration.

“Is it edible?” Someone asks of a large bracket fungus in Peckham Rye Park. The same question has been asked of every other specimen we encounter and this time David picks up a stick and pokes the surface of the fungus. “Would you want to eat this?” he says. The outer layer looks tasty but underneath, the fungus is mushy and riddled with maggots and looks distinctly unappetising. Like most things related to fungi, it is more complex than it first appears. David advises that you need to be very wary of eating even the varieties of fungus easily recognisable as edible if you find them in cities due to the levels of toxins they absorb from the pollution in the air and the soil. This is sad for anyone hoping to eat London’s fungi but it suggests another important role for them. I do a little research when I get home and find examples online of fungi being used to reduce pollution levels. It appears these organisms have far more to offer us than a few free meals.

David talks of the huge numbers of different species of fungi - around 15,000 in the UK alone - only a couple of thousand of which are potentially visible to the human eye. For centuries people were mystified by the sudden appearances of lines or circles of mushrooms and could think of no other explanation than the existence of fairies or some form of witchcraft. We now know there are more practical and less fantastical reasons behind such events. Fungi often grow along the line of a particular feature, such as a tree root that they are drawing nutrients from, and a ring is formed by fungi moving out from a central point as they use up all the nutrients around them. What would our ancestors have made of the recent discovery that trees and plants communicate via the mycelium, the network of thin threads formed from the underground parts of fungi, in a phenomenon that has been dubbed the “world wood web”? Clearly we still have much to learn about the value of fungi, particularly if we are going to include an accurate assessment of these resources in natural capital accounting.

We found lots of different fungi on our walk – honey fungus, dome caps, sulphur tufts, ink caps and more. We even found one hidden among the litter and fallen leaves next to a street tree. Their common names are a wealth of visual and sensory indicators but David warns us how hard it is to identify fungi from guidebooks as factors such as their age and the weather have so much impact on their appearance. I have been to all the places we visited many times before but I am seeing them in a new way today, suddenly aware of a vast range of species that I had not previously taken much notice of.

Here again is evidence that there are important opportunities for wildlife even in the most densely built up parts of London. Like the kingfisher in the Ravensbourne, the fungi in Peckham Rye Park are within walking distance of my home. Even closer are the fox who is a regular visitor to our street, the jay who buries acorns in the communal garden in front of our house and the woodpecker we regularly hear and occasionally glimpse high in the trees on the railway embankment. I have also seen a sparrowhawk in our local cemetery and cormorants fishing in the Thames. I cannot think how you would even begin to put a value on most of this but I do know that the wildlife in this vast and varied city is a huge part of what I value about living here. This is my natural capital.

© Ruth Bradshaw

The Naming of Brush Fires

by Laura Saint Martin

Laura lives and raises butterflies on a flood plain below the San Gabriel mountains of Southern California, former home of vineyards and citrus groves.

The sky is just an ashtray, hot-boxed mountains

mantled as wizards, our swamp coolers dystopic

with a roar that is anything but dull.

It starts as a Martian light, coppered shadows,

helicopters hung like stallions and toy

planes shitting orange. The fire soon stands

Godly, flags half the state, while we hide in cars

and gymnasiums, choking on hot snow. It looks

like it should rumble, but it whispers like water,

the only thunder our advance and retreat.

Brush fires are named for streets, campgrounds,

bodies of water. Why not name them for the victims,

the motorist whose death was the point of origin?

Why not for the leaf-shaped ash that traveled

twenty miles to collapse, little geisha, in my hand?

© Laura Saint Martin

Something about Morning

by Lois Marie Harrod

Lois lives in the Stony Brook watershed in Hopewell, New Jersey, a sweet little town that has been here since the l8th century. Though close geographically, it seems far from the turnpike-oil-refinery New Jersey.

You can miss it—

all the dying oaks and sagging roofs

between you and the dawn—

though if you sit in the rocking chair

by the second-story window

you can see apricot and azure silks

how they seem caught in the magnolia

which has already dropped its blossoms,

those little pale shoe soles

down on the new grass.

By the time you look again

the sky has gone gray.

© Lois Marie Harrod

Stormwatch

by Thomas Mitchell

Thomas lives on the Southern Oregon coast at the juncture of the Coos River basin and the Pacific, spending a great deal of time hiking the mountain trails and strolling along the beaches.

I think there’s a storm coming in, wind blowing from the South,

leaves rattling on the sumac as the morning gathers restlessly

in my backyard. A pair of stellar jays visits the pyracantha bushes

three feet from my window. Soon they grow tipsy from the fermented

orange berries. With me it’s vodka. I know there needs to be a change.

I’m hoping to be surprised tomorrow by I don’t know what.

Not by the new moon that everyone believes will bring hope,

that tilts ever-so slightly toward Jupiter, bathing in its own lustrous

light, and not my own fear which comes and goes, sometimes

with Mozart’s music or more lately, Leonard Cohen singing

So Long Marianne. What could it be, this change, but to awaken

to sunlight dancing on the window shade, and to understand

that the ways of the world are no more complicated than a shift

in the wind? It’s beginning to rain and the stellar jays lift their wings,

then fly away.

© Thomas Mitchell

Learning of Unsuitable Habitats

by Kelly R. Samuels

Kelly lives where the La Crosse River, the Black River, and the Mississippi meet and meld.

Pastures are, with their grasses and low lying

plants – sustenance for cattle and their

ambling or standing still. Their shuffle

forward after time. And the warmer space,

cleared of the wild cashew and yellow

lapacho large and strong with its flagrant

seedpod. So difficult to navigate, to travel

through to another space with the plentiful

nectar of the brazen red flower the feeder she

hung outside the porch attempted to mimic.

One of you would arrive and we would joke

of apparition. And just as quick – gone.

Looking north to where the barn slouched,

where the vines were having their way with

the wood, we would wait for you to return

with your hum and glimmer. Too sentimental

to say like a blessing, but true. So, the stands

of oak and walnuts and all the intentional

lilies are needed. And bee balm and blue

anise sage and honeysuckle – that blossom of

the hedge we trimmed every year, waiting

until late fall, carrying the branches back to

toss over the hill none of us could ever quite

negotiate to meet the water’s edge.

© Kelly R. Samuels

The Mending

“School children of America!

Help save your fathers, brothers, neighbors

by collecting milkweed pods.”

from a Soil Conservation Service pamphlet, 1945

by Rhett Watts

Rhett lives in the Blackstone River watershed yards from a brook that runs off the Lower Worcester Plateau. Her neighborhood is inhabited by American mink, foxes, bald eagles, humans and is not far from the Last Green Valley heritage corridor.

September's end, the last clematis pours

over summer's guardrails, so much spilled cream.

Seeds burst milkweed pods, a chrysalis hangs

its tiny lantern. Three gilt dots seal wings

within like rivets or the molten metal

that heals cracked pottery.

Milkweed tufts loft into air. Land seed parachutes.

Call to mind a brochure Dad saved when

the plant still covered the prairie. Millions of

pounds of fluff salvaged for the war effort.

Two pillowcases full stuffed one life vest.

Hollow white spindles trapped air,

waxy coating shed water, saving a pilot

or a sailor from drowning.

Emergent imagoes-- imaginal cells--fully formed,

or not, dry your wings. Flap and glide

heedless of the names we call you: Monarch,

Black-veined Brown, Common Wanderer.

Ride the wind to a home seen only in flight

from above this tangle of green and gold.

© Rhett Watts

Bristling Senescence

by Don Noel

Don is now six decades older, a continent to the east and 10,000 feet lower than where he punched cattle in his teens. He lazes his retirement days away near the river Quinetucket (as the Mohicans called the long, tidal river) a bit north of the state capital that came to be called Hartford.

Riding by Methuselah reminded Buck Everett that he was tired, and maybe getting a little old for this work. He’d spent most of yesterday tracking down a bull that – like all the damned bulls -- had followed some bovine whims along the-11,000-foot flanks of White Mountain and down a grassy canyon below the sparse McAfee Meadow.

With the help of extra hands who’d ridden up to help, the herd of cows and calves had been rounded up easily and driven down Cottonwood Creek. They were by now back at the ranch, whose valley browse had matured while they were up here on summer range and would be ample to get them through the winter.

And he was left alone up here tracking down the bulls, off today a half-day’s ride in the opposite direction from yesterday. He was at this moment guiding Ginger through what the Forest Service called the Patriarch Grove of the bristlecone pines and hadn’t seen his quarry yet. The bulls oughtn’t be up here anyway: They’d done their job, siring a new crop of calves, months ago. He should persuade Glen next year to leave them in the valley – or hire a younger man to round them up.

He looked across the Owens Valley to the snowy crest of the High Sierra. It sucked up any Pacific moisture that made it through central California, leaving Death Valley and most of the California-Nevada border in a gigantic rain shadow, helping make the ground under his feet – or strictly speaking under Ginger’s feet – the perfect climate for the planet’s oldest trees.

This Methuselah, the experts said, clocked in at more than 4,800 years. By the time he found this next bull and got it back to cow camp, it would be dark and he’d feel that old. In past years, Nonie had spent the summer up here with him and would have dinner waiting. This year Glen sent an extra two hundred heifers up, and some young cowboys to help tend them, so he’d spent the whole summer a bachelor.

Glen, the ranch manager, who had a college degree, liked to talk about the geology of this range. White dolomitic limestone, he said, whose alkalinity discouraged much of anything from growing apart from thin alpine grasses; the aridity reinforced the handicap. Even the bristlecones didn’t thrive there, Glen argued; they merely survived – mostly because little else in the plant kingdom is stubborn enough to compete for thin soil and maybe ten inches of rain a year.

Ginger snickered and veered off down a shallow canyon bowl. He could see a grassy bottom and a spring the size of a hat, without enough volume to carry any water downstream. Sure enough, there was the damned bull. He braced himself in the stirrups as she half-slid down. The horse knew the drill so well that Buck hardly used the reins: Get behind the bull, headed home, and it would shamble off in the direction pointed.

Beef. That’s what they were growing, and what he survived on up here, along with potatoes and canned everything else. Thin rations, like the trees. When they set up cow camp in June and drove the herd up, Cookie had a whole side of beef trucked up and hung in a kind of solid, critter-proof outdoor closet. It chilled close to freezing every night; Buck zipped it into an abandoned sleeping bag every morning to retain the cold. Every night he took off the bag and sliced off enough for dinner. It was near gone now, but maybe the best-cured beef in California. His mouth watered, thinking about it.

They were back to the Patriarch Grove. Scattered shipwrecks of trees that didn’t justify a word like grove. There were no straight, tall, round boles; trunks were thick, misshapen, only occasionally topping 40 feet, with thin bark that almost never protected the whole tree. Clusters of foliage – branches bearing dark green needles – were sporadic, and mostly on the east. Anybody could see where the prevailing winds came from.

His kids had always loved seeing these trees, he remembered, which made him think about Nonie, which took his mind to the fact that even the oldest of these trees continued to propagate. He’d chanced to see it once: the male cones had rare orgasms of pollen that impregnated their own female cones. The ensuing seeds were protected in the sharp-bristled cones for which the species was named.

And then – nature’s marvels – the mature seeds were prized by the Clark’s nutcracker, which buried them for future use in small clumps, some of which sprouted and spliced themselves into trunks that looked as though giant hands had twisted them to spiral upward.

Some appeared dead, but weren’t. In dry years they clung to life by thin ribbons of bark and cambium that carried just enough moisture and nourishment. We aging humans, Buck thought, have narrowing arteries, stiffening joints, hearts that don’t pump and lungs that don’t oxygenate as well as well as they used to. And that even though we – unlike these trees –keep ourselves for the most part in friendly climates.

For the most part. The sun was setting, and it was cold already. He’d light the pot-bellied stove as soon as they arrived, and only then put out some feed for Ginger and the bulls. All of them were beginning to grow shaggy coats, not relying on wool underwear and down vests like fragile humans.

Then he would manage to find a little meat on that well-whittled side of beef, and see what else he could scrape together for a meal -- before collapsing into his bunk.

It would be good to admire those ancient bristlecones from a greater distance.

© Don Noel

An Invitation to the Apple Harvest

by Tanya E. E. E. Schmid

After spending six years on a permaculture farm north of the Swiss Alps near the glaciers of the Eiger North Face, Tanya now resides 600 meters lower in altitude, amidst palm trees on the Southern Riviera of Switzerland, along Lago Maggiore.

If you’re lucky, the sun will be shining but with just enough clouds at midday to keep the sweat out of your eyes and your tanned arms from peeling to pink. If you’re lucky, the crop will come in full like it did five years ago and, if so, almost certainly the fruit will be ripe, providing the kind of juiciness that is sweet and sour all at once. If you’re lucky, your helpers will show up early, a patchwork of eager faces.

Maybe you decided to start an organic farm when you turned forty. Maybe you quit your job as a dental hygienist or a second-grade teacher or a hairdresser when you realized no one was going to fix climate change for you. Maybe you started the farm right out of college with a degree in Organic Agriculture and money from the corner bank. Maybe you converted the dairy farm your folks had. Maybe you hadn’t planted a seed since kindergarten and you didn’t know if you would ever get this far. In any case, you took the leap. Maybe your partner still isn’t convinced, so they’ve kept their job for when profits are low. Maybe you’re hiring workers through the unemployment office. Maybe you have a huge family who all work the fields together in their spare time. Maybe you get help from the neighbors and they get free veggies. Or maybe you’re plowing it alone.

In the city, your work is invisible. There are produce-buyers and grocery-store shoppers who complain about prices but expect you to keep their shelves full, no matter what the weather. There are people who don’t know what it is like to rise before dawn to bend low in the May rains to hand-pick six hundred slugs off the broccoli or the lettuce so that you don’t have to use pesticides, who ignore the fact that pesticides kill everything from the slugs to the vital insects and healthy bacteria that keep the soil alive. In the city, it is often difficult to see the cycle, the connection between all things.

To be sure, not everyone can start a farm. To be sure, there are city-dwellers who are dedicated composters, who buy local and organic, who plant bee-friendly flowers on their balconies. To be sure, some sow edibles along sidewalks, turn their lawns into vegetable gardens, and help out at the nearest orchard. There are small pockets of people in the city who see beyond their hunger and their cravings. They see the sacredness of growing food. They understand what you do.

They understand that your back is stiff and your muscles ache and, yes, you have known hard physical labor. They understand how you work weekends and skip vacations because if you don’t things will die, how you learned to watch the clouds, to smell for rain, to read the intentions of the northern or westerly winds, to know the names of the trees that hold those winds at bay, to build swales and bury reservoirs to retain water wherever possible. They understand that nature can be murderous to your fields, wiping clean your months-long toil in an hour of hail, three days of hard rain or three weeks without. Lord knows.

But some people talk about environmental protection as something separate from their daily lives. You bury your hands in the cool earth of it every day. The city forgets. The non-profits spin the conversation away from doing good toward doing less harm. They know the city abhors sacrifice, dislikes inconvenience, so they give people a way out of the cycle, a way to relieve their guilt, to appease their fear of taking action, their fear of change – write a letter, vote or donate to save the bees or to ban the latest pesticide.

“All natural” is a cliché, overused and exhausted in our advertising, but the fact remains: becoming part of the natural cycle regenerates the body, renews the spirit. So many of us walk through the world without becoming a part of it. When you walk out onto your wheat field and the seed heads are nodding or the peaches in your orchard give slightly under your thumb or the peas in your garden rows have swollen to match the roundness of your finger, no matter how experienced you are, how many times you have done this, you can’t help but smile. These gifts are for you. For us.

In the city, tomorrow, you’ll be selling produce for a fraction of its worth. In the city, tomorrow, you’ll ignore their sighs and sideways glances, even though you’ve kept the smaller, damaged and irregular fruit for yourself. But in your orchard, today, none of that matters.

Today, the sun is shining and the grass is still wet and the wind is gentle. Today you’re lucky: the blossoms snuck past the late frost this spring and there were enough bees back in May to do the pollinating. Today you’re lucky: the apples are ripe and will fall into your basket -- depending on the season, Gravensteins or Boskoops or Pippins or Baldwins or McIntosh. Swing the basket onto your back, step into the generous shade as wasps lift from the fallen fruit and circle your feet. Brace the ladder on a sturdy branch and climb the wooden rungs, the cider smell following you like rising steam. Emerald leaves tickle your face as jealous finches flit past. The coolness of Eve’s perfect apple kisses your palm and a rhythm emerges from medieval memories as you roll each apple upwards, releasing it from the branch with a little twist. A soft breeze cools the back of your neck, a drop of sweat runs down between your shoulder blades. You stretch further out to gather the ripest, then pull back and let the bark hug your hip as you steady yourself, shifting the weight on your back. The only task is to become part of the cycle, to be reborn under the apple canopy. Today you’re lucky: the branches hang heavy and the fruit is flawless. Your help is agile and experienced with ladders, and they cross the orchard smoothly, singing.

© Tanya E. E. E. Schmid

Music and Memory

by Robert Coats

Bob lives in the watershed of Blackberry Creek, a small urbanized but partially-restored tributary of San Francisco Bay. He may also be found occasionally in the Tahoe basin, where he is studying the impacts of climate change.

Working at my computer

barely listening to the streaming music.

A new piece begins: Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite,

solo flute and oboe taking turns,

notes falling, rising, falling again

then joined by a chorus of strings,

and suddenly I am in the Merced River basin,

sixteen again, bivouacked

with a friend on a rocky ledge

above timberline.

A rough night, not much sleep

on the gravelly bed.

Roused by the winds of dawn,

faint glow in the east,

we sit up to watch the sun

rise behind the Minarets,

a pink cloud-cap on Ritter and Banner,

the glacial moraine around us

aglow in orange morning light.

© Robert Coats