Issue Number 46, Fall 2019

Contents

- Ballad of the Dolphin by Margo Taft Stever

- End of Horses by Margo Taft Stever

- Nightsong, Autumn by William O'Connell

- Rain on Dry Leaves by Rachel Rose Teferet

- Geese by Gene Berson

- The Santa Fe Trail by Scott Laudati

- Leaping Doe and Fawns Flash Before Us by Rodney Torreson

- Grayling by Eric Chiles

- Bearly there by Eric Chiles

- Spring Hill by Mark Seely

- Verge by Susan Cohen

- Called to the Forests by Polly Brody

- Future Tropical by Ross John Farrar

- Fiji Water: Spin the Bottle by Gerard Sarnat

- America’s Ecosystem by Carroll Grossman

- Bees by Michael Montlack

- Ocean Gyres Turn by Janferie Stone

- Salvador Dali and the Glacier by Michael Trussler

- Until Only Scars Remain by Will Falk

- Unrepentant Moon by David Dodd Lee

- Eli the Lamb,

Lower Longley, Tasmania by Rafaella Del Bourgo

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

Ballad of the Dolphin

Ancient Greeks said they should be treated

as humans; their sailors would not kill dolphins.

by Margo Taft Stever

Margo lives on a bluff that rises above the Hudson River at a point more than three miles across where the river is close to its widest. This is the portion of the river that the Dutch called the Tappan Zee. Nearby cliffs contain lines from the geologic period when the glacier advanced southward.

How I have thought of you

caught in the fishermen’s nets—

they would set them to trap

you to catch the tuna

that swam under your schools.

How the fishermen hung

you still alive, upside down—

your cries brought others.

Fishermen grabbed you by

your tails, strung you, and turned

you, head down in water, tied

you to lifting hooks,

and dragged you to the docks. If any

of you were still alive when they slung

you on cement, they stabbed you.

How last survivors churned

the water red, leaping in panic,

waiting to die. In a “good” catch,

it took them three days to kill

all of you. How mothers whose calves

were entangled could not lift them

to the surface. They listened to their helpless

underwater clicks and sighs.

How often I thought of the whale skippers

who would radio the location of hundreds

of you, allowing tuna fishermen

to track down your entire pod. Think

of their nets, deep, foaming, wide,

so that hundreds could fit inside. How they

used underwater sound

to confuse and drive you down—

how many of you drowned.

Fishermen did not want to compete

with you, but killing you was not enough.

How they used the screams

of several to slaughter more.

How one of you hangs from the prow,

still alive, calling, calling.

Previously published in the author's chapbook, Ghost Moose (Kattywompus Press, 2019)

© Margo Taft Stever

End of Horses

by Margo Taft Stever

Margo lives on a bluff that rises above the Hudson River at a point more than three miles across where the river is close to its widest. This is the portion of the river that the Dutch called the Tappan Zee. Nearby cliffs contain lines from the geologic period when the glacier advanced southward.

I write to you from the end

of the time zone. You must realize

that nothing survived after

the horses were slaughtered.

We sleep below the hollow

burned-out stars.

We look into dust bowls

searching for horses.

When you walk in the country,

you will be shocked to meet

substantial masses on the road.

We do not know whom to blame

or where the horses were driven,

who slaughtered them, or for what

purpose. Had the horses slept

under the linden trees? The generals

and engineers pucker

and snore on the veranda.

Previously published in the author's chapbook, Ghost Moose (Kattywompus Press, 2019)

© Margo Taft Stever

Nightsong, Autumn

by William O'Connell

Bill lives in the Connecticut River Watershed between “The Great Beaver” (aka Sugarloaf Mountain) and the Hadley Range in Emily Dickinson's town.

Tell me, steel-belt moon

rising from the Quabbin,

do you still hold the heart

of the forest where you shine

on the movements of mice

between trees? Are you what

held the coyote’s single howl

last week below our bedroom window

to lift us momentarily from

the daily grind of dying?

How your light, for instance,

intersects the darker

reddening of leaves,

the desire for desire amid

the wilderness of God’s disfavor,

our souls twisted into shapes

we can’t manage?

In the bare garden, I wander,

unable to sleep.

Some lettuce still pokes up

from its rubble.

In moonlight, poetry is diminished.

Say less, be quiet. A slight breeze

rises, falls.

© William O'Connell

Rain on Dry Leaves

by Rachel Rose Teferet

Rachel lives in the Bear River Watershed, upon the banks of Wolf Creek, where she howls under full moons. She goes often to the Yuba River, where she drapes herself on sunny rocks and writes poetry and romantic comedies in the shade of the willows.

drumming frog song

the last cicada hum.

Fragrant earth

breathing like an attar

in a base of sandalwood

and my bones

melt into my bed

dreaming past thin membranes,

illusions separating

me from you—

I swim

past the portal

to the source of rain

all water

at once

© Rachel Rose Teferet

Geese

by Gene Berson

Gene lives in the northern California foothills in the Yuba River watershed. Everyone goes to the river. Like a temple, with its falls its rapids its green pools, it seems to restore everyone in a personal way. We feel our kinship through it.

I thought for a second they were bowling pins

balanced on the bank of the drained reservoir

but they were so attentive

beaming in a radiant aura, a devout

congregation of little monks robed in light

soaking in the last rays of the sun.

Their brown-hued breasts swelled

filling with the day’s last warmth—

about twelve of them.

we didn’t think we’d disturb them

since they seemed far enough away

on the opposite shore

but one started working the rusty hinge of his voice

and they all gently took to the air, flying as if one fabric

layering the valley with trombones

spiraling higher as they circled the reservoir

passing above us, lifting just enough

to thread an opening in the trees.

But what if we had been more patient

crouched on our haunches

in the shadows at the base of the trail

and attended the last light with them

felt the coolness come, the darkness, and when

they took off, unable to fully see them

listened to their wings

as they swept overhead and escaped

with that part of ourselves

no one can see?

© Gene Berson

The Santa Fe Trail

by Scott Laudati

Scott lives near the East River between the superfund site of Greenpoint and the toxic sludge of the Gowanus Canal.

you can read maps by starlight

in places i've been

and you sleep like shit

off the mexican beer

and wake up covered in bites

in hotels where

life is impossible

and everything still alive

wants blood.

did you know what you wanted

at the taco truck in dale hart?

do you know that there’s a

whole country out there

that doesn’t care about new york?

i do now.

i might know everything now.

i’ve drunk from the shallow creeks.

i've chewed the tacos rellenos with

fire still in the seeds.

i looked up for god and every grackle

in the tree followed my gaze.

next time i’ll follow the trails in the sand

and the small streams will lead me to the window rock.

or maybe the other way -

to lie down in a graveyard

where desert rats use cow skulls as ashtrays.

and if the rains ever come again

maybe white petals

will bud up from my bones

and a lost rabbit can

spend a day

sleeping under my shade.

© Scott Laudati

Leaping Doe and Fawns Flash Before Us

by Rodney Torreson

Rodney lives in Grand Rapids, along the Grand River, which Native Americans originally named O-wash-ta-nong, meaning “far-away-water” due to its length. Its rapids have been gone for well over a century, since the building of many dams in the mid-1800s, and “white caps” now more often refers to the city’s minor league team than waves cresting in white foam.

in foliage and street, on the fringe of this city,

deer we encroach on,

then fret over their lives spent

in a startle

we share in each encounter.

We settle for

trying to count them

instead of lingering over what it all

means when they show themselves late

and early in that interlude

when traffic’s not attacking Haines Street.

On the road and through open

spaces beneath

a maple’s canopy—

near the driveway we share

with neighbors—we spot them

far from airy reeds and water.

My wife says, grinning,

they’ve been eating her hostas.

The deer, gone in light, bristle

through the bare stems

they leave for us.

We imagine our scent tousled

within them, as if

they’re too taken with us.

Browsing my way back

into the stand of trees, I saturate

their bony bough and antler-like

branches with my scent, hoping

they’ll get over us and flee,

the doe at night impossibly hiding

fawns and herself

under the one hulking

maple.

September, when leaping begins

deeper in their bones,

the springing forth

flightier, doe and fawns

live inside the startle

and we recover counting

in the wake of quickening

headlights, the sets

of perked ears

that tarry for seconds

before fading.

© Rodney Torreson

Grayling

by Eric Chiles

Rain from Eric’s roof drains into the Monocacy Creek, a tributary of Pennsylvania's Lehigh River, which drains into the Delaware.

Where the paved road stops

and the gravel starts,

the Denali Highway crosses

the Tangle River

ripping across the empty tundra,

an open vein over the rolling, brushy

skin of this alpine

valley stretching forever

through the vastness

of the snow-draped Alaska Range.

The only things that seem to move

are the water and the wind.

In a land of caribou and grizzly,

all we see as we walk to the Tangle

are clouds of mosquitoes.

But arctic grayling thrive

in the Tangle's swift

amber as we wade over

its slippery, mossy stones

with our fly rods.

Small ripples break the surface

by the far bank

where clots of grayling feed

on flies floating by

like a riparian buffet.

So, I tie on an elk hair caddis

and cast that way,

lifting my rod tip when one

rises to take the fly

then slices the water with the line.

I unhook it in my net, unfurl

its sail-like dorsal

with my thumb, marvel that the Tangle

hides such a silvery corpuscle,

feel the tundra's wriggling pulse.

© Eric Chiles

Bearly there

by Eric Chiles

Rain from Eric’s roof drains into the Monocacy Creek, a tributary of Pennsylvania's Lehigh River, which drains into the Delaware.

From my perch in the tree

I see a pile of scat near the foot

of my ladder. Then I notice my

trail camera isn't on its stump,

and I wonder if the crap is some

kind of calling card.

When I get tired of sitting,

I get down and find the camera

half buried in the leaves

near the stump and another

brown clump of fresh scat

full of masticated acorn husks,

and I begin to suspect a large

omnivore is trying to tell

me something.

Sure enough, when I check

the camera's SD card in

the laptop, there's a frame

at midnight of a shiny snout

sniffing the lens, then another

of black serrated by white,

a teardrop of drool followed

by nothing until morning

when the camera captures

the grasping mouth

of my palm.

© Eric Chiles

Spring Hill

by Mark Seely

Mark lives along the westernmost reaches of the Cedar-Sammamish watershed, a short, steep, uphill hike from the estuary of Lunds Gulch Creek, where Chinook and Coho salmon abandon their freshwater youth and enter the southern finger of the Salish Sea known as Puget Sound.

Drumheller’s Spring was the official name, posted in large yellow letters carved into a brown wooden sign near the sidewalk, but everyone I knew called it Spring Hill. Spring Hill was a marshy area atop a sullen outcropping of basalt, still brooding after being abandoned for eleven and a half millennia by the glacier that brought it there. It was bounded on the south and east by a broken line of steep moss- and lichen-encrusted cliffs that plunged at various points from ten to perhaps forty feet before being absorbed into the sloping bush-covered alluvium. A half dozen or so small springs trickled out of the rock face. The largest spring was corralled by a time-worn concrete trough that channeled the water alongside a broad steep footpath to a small collecting pond, where the overflow was siphoned into a grated sewer drain for a two-mile trek south to the river. The path next to the concrete trough was adorned in spots with rusty ruins of an iron-pipe handrail and littered at irregular intervals with slick angular rocks that served as natural stair steps. A large field lay above the spring and across a dirt road to the northwest. The field was flat, broken in irregular intervals with small grassy mounds and rock outcroppings, and almost treeless. It was home to three small ponds, the two smallest of which were seasonal and disappeared in midsummer. The largest pond supported a wide variety of aquatic and semi-aquatic creatures, including fairy shrimp, turtles, a variety of frogs, and a small species of salamander with an indigo body and an almost iridescent yellow-green stripe down its back.

Spring Hill was surrounded on all sides by residential neighborhoods, and positioned along a major traffic corridor consisting of north and southbound one-way two-lane arterials—both of which were forced to make an abrupt guardrail lined curve to accommodate the cliffs. I made the five-block journey from my home two or three times a week, starting from when I was eight or nine, until we moved to the far north side of town when I was fifteen. It was the running water that first attracted me. My friends and I would have races with pieces of bark starting from where the large spring emerged from the pipe down to the collecting pond. Some days we would build tiny dams or gouge small tributaries into the hard clay of the banks in spots where the concrete had eroded away. The animal life was next on my list of interests. Pond water is teaming with alien creatures. And it was not uncommon for me to have a mason jar of Spring Hill pond water sitting on my bedroom windowsill. The salamanders were the big prize, though. One day I collected over twenty in a single hour.

As I got a bit older, the cliffs themselves started to beckon. The tallest rock faces were along south side toward the western edge of the area. My friends and I spent many afternoons daring each other up the lichen-encrusted basalt. There were a variety of routes, some easy enough for my little sister, and others that had overhangs and bald surfaces that would challenge a veteran rock climber. At the base of the most formidable cliffs, stood a wooden plaque next to a couple of well-weathered stumps of charred lumber that announced the area as the site of The Chief Garry School before it burned down. Garry, whose real name was Slough-Keetcha, was sent by his father the Chief of the Spokane Tribe to a missionary school in Canada when he was fourteen. He came back as a young adult, built and taught at his own school, and fought to maintain his tribe’s rights to live along the Spokane River. He lost his fight and his school.

Both the wooden plaque and the charred remnants of the school are gone now, absorbed into the backyard of one of the many houses that have been built along the Cliffside. Instead, there is a five-foot rectangular granite obelisk with rough-hewn edges next to the road that runs along the field where the smallest of the seasonal ponds used to be. The highlights of Chief Garry’s life story along with some of the physical details of the school are carved into the face of the stone: “The school house, 50’ X 20’, was constructed of pine poles covered in yule mats, sewed together by Indian women.” There is something about the choice to include that last detail, that Indian women did the sewing of the mats, that bothers me, but I’m not sure why.

I am at a loss to describe the personal significance of Spring Hill. To say that it was formative seems to trivialize its impact, and to discount the influence it has on me even now. Medical researchers have found that childhood exposure to outdoor environments protects against later development of allergies and asthma. Other studies have shown that childhood exposure to the natural world is linked with environmental concern as an adult. I suspect that these two sets of findings are not unrelated, and that early exposure to natural spaces enhances both physical and psychological immunity. I suspect also that the connection between early nature exposure and later environmental concern is not simply due to the workings of nostalgia. One of the most general features of human psychology as it relates to our understanding of the world around us is something cognitive psychologists refer to as WYSIATI: what you see is all there is. Despite the unwieldy acronym, the idea is rather straightforward. We can only work with what we have experience with. If we stumble upon something new, and there is nothing in our past to hang it on, if it falls outside of our experience or our current understanding of the world, it may as well not exist. As civilization continues to expand its global expression, wild nature will fall increasingly outside of everyone’s experience, and no one will ever know what it is, exactly, that is missing, but they will feel its absence nonetheless.

Today Spring Hill is an urban anomaly, a tiny time-forgotten microcosm of wild nature surrounded by busy streets and residential neighborhoods. For the women who sewed the yule mats for Chief Garry School, however, Spring Hill was nothing special, nothing unusual, probably even mundane. Then the entire valley that now contains the city of Spokane—which has long since sprawled up and out of the valley and is rapidly spreading in all directions like a malignant skin cancer—was Spring Hill. The entire world before civilization was Spring Hill. And, although neither you nor I will be around to see it, we can take some solace in knowing that, with time, the entire world after civilization will eventually become Spring Hill once again.

© Mark Seely

Verge

by Susan Cohen

Susan spends much of her time looking for birds in both the San Pablo Bay and the Bodega Bay watersheds of Northern California.

Black night, and an opossum

on the country highway

shuffles as fast as it can,

its cumbrous walk taking it

to the grass verge or else

to heaven in a cloud of diesel.

Cars gun by, the creature ashen

in each headlight—a flare

any tire might squelch.

We slew wide and miss it,

hoping the drivers behind us

also swerve. At least

it won’t be us—no thud,

no small regret—diminishing

an already thinning world.

We leave the opossum

where we found it, not yet

to the verge, though on it.

© Susan Cohen

Called to the Forests

by Polly Brody

Polly lives in an exurban Connecticut town, about 500 ft. above sea level, about an hour's drive inland from Long Island Sound. Every year she listens from her window for the first chiming peep of spring hylas that give voice to a pond, just within hearing.

We describe our world as the “blue planet,” and yes, seen from space it is a swirl of white clouds over blue seas. However, there is another color vital to our planet’s health; it is green—the living green of forests and savannas, of gardens, and the indispensable phytoplankton that blooms in our oceans. All these bank carbon, while contributing to and maintaining oxygen in our atmosphere.

. . .

Tropical rainforests are a choir of green. Their trees reach high overhead, forming a dense, unbroken canopy. There is a secondary level of lesser trees beneath the crowning canopy, and these layers of green so effectively intercept sunlight that at ground level, a shadowed atmosphere exists that seems like the undersea bed of a verdant ocean. Indeed the humidity is such that the air feels almost liquid.

Only slivers of direct sunlight reach the ground. The jungle is yeasty with life and rot and life anew. From the tiny carmine frog cupped within his leaf, to the jaguar that may walk the forest floor, bearing its dapple on his back, creatures are embraced and nurtured by this world—one can feel a great heart pulse.

This is habitat in which a chorus of avian voices exalts at dawn and sings through the morning. Voices heard but birds unseen. Until suddenly, there is a Crimson Topaz Hummingbird in gleaming hover, caught within a stray sunbeam that has managed to reach the forest floor. Or a brief glimpse of the Musician Wren—small rufous bird, with a blue eye ring—perched momentarily on a fallen log. Its flute-like song entrances the air, but this songster is rarely viewed. I waited many patient minutes for my once-in-a-lifetime glance.

What is the allure we find in mystery and why the special satisfaction felt when one attains a personal revelation? For me, the more challenging it is to view a bird whose voice is present in that lush forest, the greater my delight, should it finally present itself.

The music and magic of Pan’s pipe has called me to rainforests of Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador and Australia. Deeply felt moments have blessed me in each. Here is one from my Australian trip’s journal.

“Today, I hiked six miles out from the Lamington Park lodge. My daypack contained sandwiches, fruit, and a bottle of water. Over my shoulder rested my tripod. On it rode my camera, with its attached telephoto lens. The highland’s temperate rainforest canopy let little sunlight reach the ground, so the air was cool. I felt I was walking in a subtly lit, vast hall. All along my way I heard the dual outcries of the whipbirds, so named because their paired vocalizations sound like a whip cracking.

I reached the escarpment that was my goal. The forest had thinned in the last kilometer, and now I emerged into full sunlight, finding myself on open ground approaching the verge of the great ravine. It was the overlook I’d sought—an immense landscape of slopes, clothed in trees. These were the famed “broccoli forest” views of which I had heard. The green crowns of those massy trees were round, packed tight one against the next, and lumpy in texture. Seen through my binoculars, they looked indeed like bunched broccoli. The land, falling away on both sides, and before my feet, gave me the sense of a giant bowl cupping the sky…a vast silent space embraced by this spacious, verdant chalice.

But, not silent…a plaintive skirling sounded from the escarpment’s far side. I raised my binoculars and scanned the distant forest tops, seeking its source. What bird might I find there? Then I saw them, a skein of Black Cockatoos gliding down-slope. These large birds at that distance, miniature, even through my field glass, their raucous calls attenuated across the bowl of space; their downward drift along the forest wall a lyric grace.

Yes, gifted to have experienced such moments in the undisturbed wild woods. Yet the heart blanches when one understands the onslaught now in progress. Over recent decades, and continuing at an accelerating pace, the great forests clothing our world’s tropical latitudes are being “harvested,” cut down and cleared away, reduced in their extent to a degree that threatens climate and soil stability, promising consequences as potent as those from global warming. We pour carbon dioxide into our airs, while erasing the very living green that would return oxygen while utilizing that carbon dioxide.

Removing the benevolent cover of tropical forests exposes the ground to a merciless sun, changing its fecundity within a handful of years to baked lateritic soil not even able to support healthy grassland. In addition, tropical rains yearly wash this exposed earth away into streams and rivers. The jungles’ rich treasure houses of animal and plant species are decimated along with their trees.

I first experienced a tropical forest in Panama, where I spent 18 days with an Earthwatch research group. Our project was to mist-net birds that inhabited the ground level vegetative zone, record the variety of species captured, weigh and band each bird, then release it unharmed. Mist nets are filamentous tiers of black netting strung between aluminum poles. Birds flying into them are entangled but not injured. It is an art of the utmost delicacy and agility of fingers to unwrap each bird from the black threads imprisoning it. I frequently chose to be the scribe, as my fingers were clumsy at best for such a challenging task.

We furled those nets every sundown, before returning to our sylvan camp along the Pipeline Road—not a road but rather a dirt jeep track. Nets were furled to prevent the entrapment of bats and any nocturnal birds. We would not be tending the net lines until sunrise each morning. During the day, we patrolled our nets every hour, assuring no bird was held prisoner longer than that.

Dr. James Karr, professor at the University of Illinois, was our research chief. Evenings after our camp supper, he lectured on the ecology of a western hemisphere rainforest. We learned bird species are extremely localized within its three vegetative zones: canopy species do not inhabit the forest floor; birds of the middle level rarely venture into the canopy foliage, nor are they common in undergrowth below; while those species living within the ground level zone do not ascend to higher elevations. Thus our nets, all except one line placed halfway up a slope, ensnared only bottom-zone inhabitants.

I was very impressed to learn that these bottom-zone species: antbirds, antwrens, antpittas, antshrikes, and many others that had evolved to live in a shadowed world rarely invaded by sunlight, would not even cross the Pipeline Road to enter the forest on its opposite margin.

Thus it is that opening a tropical forest by lumbering, even to a moderate extent, has a disastrous effect on many in its avian population. Of course, not only birds, but the whole intricate web of living organisms that has evolved suited to this sylvan universe will be ripped apart.

It will be dreadful if, in a future our grandchildren may inhabit, earth seen from near-space will show vast, pinkish scabs—desert where once was green.

© Polly Brody

Future Tropical

by Ross John Farrar

Ross lives 20 minutes north of San Francisco in an area blessed with trails, swimming holes, national parks and the great natural beauty of the Pacific coast. The area’s most striking feature is Mt. Tamalpais, the highest peak in the Marin hills, which can be seen from virtually any vantage point in town.

We will go to Glendale Blvd to watch the parrots sit.

They will move their heads, sensual & slow, or raise a talon

to let us know they are real & we will smile at this.

The window will say “Pampered Birds” & we will think

about comfort,

that we are human & want to be touched.

Like the time we danced in Koreatown, how I almost

dropped you

during the dip. A naked man played his piano in the corner

while we were unaware of the water slowly creeping up our

legs

& over our heads.

But at that window we will not remember this.

We will only see a false paradise–the violent red of a

feather,

the jet-black hook of their beaks.

A woman will open the door to let her children in & again

& again we will go back to this moment only to find brute change –

the birds repeating a phrase, but we cannot hear it

through the glass.

Previously published in The Chaffey Review

© Ross John Farrar

Fiji Water: Spin the Bottle

by Gerard Sarnat

Gerry lives in Portola Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula on the eastern slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The Windy Hill Open Space Preserve is a large part of the town's southwest side, and the north side of the town borders Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve.

Donald Trump just sipped it.

Little Marco botched it.

Obama drank it.

Paris Hilton loves it.

Mary J. Blige won’t sing without it.

How did a plastic water bottle, imported from a military dictatorship

thousands of miles away, become the epitome of cool?

The company’s mantra, “Every drop is green,” is fake news.

Taking water from the land and sky, putting it into containers made from oil,

and shipping it around the world defies core eco-friendly values.

Plastic bottles kill wildlife.

It costs more to drink bottled water than to put gas in your car.

Pacific islands, including Fiji, could soon be under water.

© Gerard Sarnat

America’s Ecosystem

The wildlife and its habitat cannot speak, so we must and we will.

Theodore Roosevelt

by Carroll Grossman

Carroll lives most of the year near Bear Grass Creek, where she runs along the stream to Cherokee Park. For the last 20 years, she has spent a few weeks each winter in South Texas near the Rio Grande, where mesquite grows and road runners lead her along paths beside huisache trees in bloom.

Here we are on a partly sunny January afternoon at Santa Ana Federal Animal Refuge in South Texas near the Rio Grande along with those one expects to show up at a rally to save a great natural and national resource: The Audubon Society, counting, photographing and researching; the Sierra Club, flexing its political muscle that succeeds from time to time in preventing protections for the environment from being lost; and politicians who support our cause and who also hope to enjoy coverage to win another election. Representatives from many states are here as well as documented and undocumented friends from south of the border. The rest of us, hundreds in number, want to do our part in saving a fragile ecosystem that cannot be recovered once lost.

Santa Ana provides a corridor for migrating birds and mammals, and it gives access to people young and old to observe native and migrating animals in their habitat. Life in the refuge offers an ongoing education for all who enter here. Languages color the landscape: Spanish, English and bird. The mix of languages pleases me.

Santa Ana has been a favorite natural area for my husband and me to visit for hiking, biking and canoeing for ten or more years of visiting South Texas.

* * *

Eight years ago, I stumbled as I strained to carry my half of a two-person canoe. A fleet of canoes and a van full of park visitors had been delivered over narrow, rough roads that served fields of cabbage, cauliflower and cilantro to a place of portage near an old barn. As we stepped down from the vehicle, women exchanged knowing glances and hurried behind the barn to relieve ourselves before embarking on a four-hour journey on the Rio Grande.

I stumbled as I hurried, carrying a bottle of water and an apple in one hand and in the other, the aforesaid canoe. I stumbled, but I didn’t tumble down the steep bank. A ranger held the canoe steady as Harland stepped like a long-legged Great Blue into the canoe and settled himself into the driver’s seat. He held the canoe steady as I clambered aboard and inched forward to sit front, my oar at the ready.

Little did we know that we were entering a theatre of the world’s most creatively choreographed and directed opera. The theatre is beyond beautiful. Our oars rippled through soft, green waters while overhanging tree branches and blue sky provided light and set. We were bound by huisache trees showing off delicate yellow blossoms. The aria began with the calls of birds hidden in branches of trees low over the water. I identified a cardinal, a mockingbird and three green jays. Great blue herons stood in shallow water near the shore, their legs bent for take-off as a great kiscadee flashed his yellow markings and black headband just above the heron. Two kingfishers flew in from stage left to join the spectacle.

Cormorants dived for fish, tails up like fans out of the water. Love stories unfolded as we drifted. We drifted as we listened to raucous choruses sung by hidden Altamira orioles and scarlet birds whose names I did not know.

We remained dazzled as we returned to climb out of the rented canoe and crawl back up the bank. I didn’t climb as gracefully as the birds flew; however, my spirit felt light and at peace.

Once back at the park, we followed signs of javelina and heard about resident jaguarondi and ocelots. I ran behind a roadrunner with its ruffled look and skinny legs like those of a distance runner too old to run but too late to forego a lifetime pleasure. I loved them.

* * *

These are memories. Homeland Security forbade the canoe trips five or six years ago, saying that we need to protect the U.S. border from friends, family and workers who live across the Rio Grande. The government plan is to build a wall right down the middle of the preserve, interrupting the migratory paths of endangered plants, birds and mammals. As climate change accelerates, wildlife will have to travel further afield for food and water. The wall separating refuges on either side of the Rio Grande may be all it takes to destroy fragile species. A border wall will affect residents of Santa Ana, all of South Texas and, in time, will impact all the citizens of the United States and Mexico.

Theodore Roosevelt, more than one hundred years ago, understood the benefit to all of preserving great expanses of land for future generations to enjoy. We don’t realize that the need to protect wild places of natural beauty is now. The losses are not recoverable.

* * *

So here we are. We protest the wall, we sing, take photographs, and wear t-shirts that proclaim our resistance to the border wall and our support for Dreamers. A young man steps up onto a temporary stage to tell his story. He was born in the United States, attended college here and holds a job in computer science. Twenty-five years ago his parents entered the U.S. illegally. They found work and raised their children in the Rio Grande Valley. Now one of these children, who was born and has lived his whole life in the United States, is threatened with deportation. He’s educated, he’s productive and he pays taxes.

College students who only want to remain to be allowed to finish their college education speak. We cry in response and ask each other, “Are we inhumane and stupid?”

We move from the tent to tables where information is distributed and petitions signed. We sign them all, then walk to the bird blind inside the refuge where we observe the beauty of the birds as they come and go collecting seeds at all the feeders. They take a few seeds, then fly to a nearby bush or tree, their protection from predators. I watch them with sadness and yearning, as I might grown children getting ready to leave home to engage in foreign combat, little knowing when or whether they will return.

A bulldozer is like a bomb that wipes out all the life in its path.

© Carroll Grossman

Bees

by Michael Montlack

Michael lives on a street with twin parks split by an avenue on an island that is bounded by the Hudson River to the west and the East River to the east.

After the expulsion

the planet will listen

through its wounds

for our music, seeking

to mine honey from

the amber flesh of peaches

or mangoes, harvesting

only an oozing grief,

the hive gone relic,

a waxen geometric skeleton,

its marrow a memory,

museumgoers lining up

to pay for a taste.

© Michael Montlack

Ocean Gyres Turn

by Janferie Stone

Janferie has lived on the Pacific Coast since she was 18. At present she lives on the slope of the Navarro Ridge between Salmon Creek to the north and the Navarro River to the south.

Algae bloomed seven years ago

birthing sea-star-wasting syndrome,

killing most of nineteen species:

the six-armed reds, five-armed ochre’s,

the giant sunflower stars,

sometimes twenty-six arms.

their bodies fourteen inches across.

Voracious those predators but now gone. Shells

empty, dissolving, returning to the original slime

of existence, goo seeping to the sea floor

where, in the rocky substrate,

purple urchins rose, unchecked,

exponentially growing from ten to a thousand

eating first at the feet of bull kelp forests,

their holdfasts, then the haptera branches

and then up their trunks, stipes rising

sixty feet in the tumble of waves

in the warm water of the reversed ocean gyre

the surface waters sluggish, stagnant ponds, heated,

and below no cold upwelling of food bearing water,

no bloom of krill.

The bull kelp wilted and

let go with their loosened toes,

the canopies of the vast forests drifting,

torn from their holds when

the drought ended and massive winter storms

threshed and heaved the float bladders to the shore.

Kelp grows from spores each year,

but could not bloom in the urchin desert,

in the dust bowl beneath the waves.

Ascending the water column, starvation and death.

Red urchins, uni, their sex organs shrunken,

non-reproductive, can no longer be sold

for Japanese manhood rites.

Abalones wither in their opalescence.

Thousands of tiny shells litter beaches,

gathered into nests of broken promises.

South in Monterey and north to Alaska

sea otters edge closer to the zero precipice,

for the keepers of the kelp world have no more to keep.

And orca packs hunt otters, harbor-seals, sea-lions,

while their prey and kin, the humpbacks,

the migrating grays and their calves

seek the echoes of a forest refuge

the manna of existence

in the barrens of our spiraling time.

© Janferie Stone

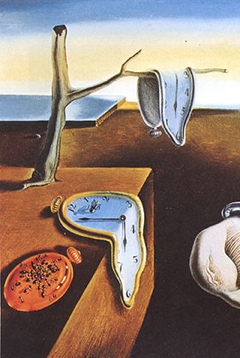

Salvador Dali and the Glacier

The goal is not to make a story but to experience the whole mess... There are the spent casings of history to sift through, pick up, and examine. Calm-like, hysterical, forensic.

C. D. Wright

by Michael Trussler

Michael lives in the wide-open spaces of the northern Great Plains of North America that’re now part of Treaty 4 on Turtle Island.

Not the persistence, but the forfeit, of memory. It isn’t clocks

but the future that’s been melting. The twentieth century

keeps gathering itself, dying. Homo faber: there was a time

when talking dolls, automatic elevators and hearing aids were

new, marvelous. Today has its own brand of what’s new

again: let’s make a deal and behind door number 3

Antarctica’s shrinking Thwaites Glacier falls out, face

down, embarrassed, and set spinning adrift

across the floor. The future’s pitiless and melting. One of

our dirtiest little secrets: this endless fondness

for endless delay.

From an illegally downloaded inflatable

raft for refugees to huffing model airplane glue to the mobile

appendectomy app, there are simply too many time

bombs to contain, the private pathways

of a mountain gorilla sanctuary

not excluded.

Recall the ancient, submarine Exocet.

This is cardiac ischemia. This is predictable

as AI, and moody too: this is Gutenberg’s invention

of consensual memory. People ferrying auditory

hallucinations. A masterpiece and an optimist

by nature, the ocean’s asphyxiated and the unborn

are marooned inside what we do and what

we don’t do. Squandering

the poorest is perfectly legal

and technically simple. What’s here now isn’t

finished with its rage for collapse.

Ice is losing its various

names and it’s not only avian malaria that’s on the rise.

I’ve never

been here before, have you? Has anyone?

We live as though there’s an inescapable

clause in our human

contract stating that even moon dust requires

the accompanying paw prints of an

apex predator, a Schleich jaguar

will do, and the awaited appearance of some

unrecognizable creature, a mumbling Jesus come

round at last and then abandoned somewhere

in the horizon’s suddenly → become

a land fill. Here we enter the newest

of possible worlds: charismatic as Thanatos

richly undocumented, and finely

illustrated with the precision of pixels

beginning to sag . . . nor forget

homo faber

to plant each grave with imperishable acorns to offset

both the Fabergé egg and the flimsy rescue attempt

of everyone’s improbable vanishing as we eventually

hear ourselves as . . . outcasts swarming to stay—

Note:

Possibly the most iconic painting of Surrealism, Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) depicts clocks drooping over a landscape and can be found in MoMA’s collection in New York City. In “The Hour of Our Death,” Philippe Ariès mentions how the Marquis de Sade stipulated in his will that acorns should be planted over his grave so that eventually the site would become part of the forest again and the grave, like his legacy, would disappear.

© Michael Trussler

Until Only Scars Remain

by Will Falk

Will can usually be found somewhere in the Wasatch Back pondering starlight on juniper berries, wondering at the diverse dialects spoken by aspen groves, or basking in the warmth of sunlight filtered through pinyon pines.

I want to give up. Each morning the headlines are heavier and my heart buckles under the load. A United Nations report, prepared by 145 experts from 50 countries, warns that one million of the planet’s eight million species are threatened with extinction by humans. This comes after a recent report by the Living Planet Index and the World Wildlife Fund which reveals that, since 1970, 60 percent of all vertebrate wildlife has been destroyed. The outlook is grim for invertebrate wildlife, too. Groundbreaking research describes how flying insect populations fell by 75 percent in just 27 years in Germany, prompting scientists to declare: “The insect apocalypse is here.”

The bad news globally reflects my bad news personally. I am an environmental lawyer. I became a lawyer because I saw law as a tool to wield in the service of life. I’ve devoted my career to protecting what’s left of the natural world.

It isn’t working.

Not long ago, I helped to file the first-ever federal lawsuit seeking rights of nature for a major ecosystem, the Colorado River. Despite the fact that nearly 40 million humans and countless non-humans depend on the Colorado River for fresh water, the Colorado River is one of the most abused rivers in the world. We filed the lawsuit hoping to gain meaningful protections for the river as a major source of life in the region. In response, the Colorado Attorney General threatened us with financial and ethical sanctions if we didn’t withdraw the lawsuit because our argument that the Colorado River should have similar rights to those possessed by the corporations destroying her was, according to the AG, “frivolous.”

I’m currently involved in helping citizens of Toledo, Ohio, defend a rights of nature law for Lake Erie from attack by agricultural interests. The law, titled the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, was drafted by citizens of Toledo after their tap water was shut off in 2014 due to a poisonous harmful algae bloom. These blooms are fed by phosphorus in manure run-off primarily produced by corporate agricultural operations. The Lake Erie Bill of Rights, which was enacted through one of the most directly democratic processes available to American citizens – a citizen initiative process – was passed with 61 percent of the vote. Without regard to the clear expression of political will expressed by 61 percent of the Toledoans who voted for the law, the City of Toledo agreed to a court order preventing the City from enforcing the law. And, the grassroots organization who ushered the law through the initiative process has been denied the ability to intervene to argue on behalf of Lake Erie in both the federal district court and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Lake Erie Bill of Rights, despite all the effort put into its passage, will, almost certainly, be invalidated without ever going into effect.

More and more, I realize the change we so badly need is unlikely to ever come through the legal system. Sure, we sometimes succeed in delaying destructive projects when corporations make a mistake in filing their permit applications. But they always correct the mistake and the destruction continues. Yes, we sometimes succeed in protecting an endangered species from the most direct threats to their survival. But we have not alleviated the global processes, like climate change and human overpopulation, that will likely spell endangered species’ long-term doom. True, we have brought a growing awareness of ecological collapse to the general public. But awareness is a primarily mental affair happening within human heads while environmental issues are physical problems happening in the real world and they require physical, not mental, solutions.

Despair pushes me into my backyard where a small voice within me, growing increasingly louder, tells me to give up. When the problems are so big and the vast majority of people simply don’t care, the voice demands, why are you struggling so hard to fight back?

The Wasatch Mountains, looming in the west above the Heber Valley where I live, help me keep that nagging voice at bay. Across most of the world, the horizon is boundless. When burdens are too much to bear, you may spill your consciousness across the landscape. You can let your mind run to that place, always pleasantly just out of reach, where land meets sky. You can let your thoughts slip down the perpetual curve of Mother Earth’s body where you can lose your anxieties in her vastness.

But, not in my backyard. The Wasatch Mountains hold my soul in place. They won’t let me hide. They stand high and proud, displaying their injuries. I never doubted, but the mountains pull my spirit like Thomas’ fingers into Christ’s wounds. Roads slice across the mountains’ shoulders. Swathes of forest, clear-cut by ski resorts for ski runs, are lacerations that stripe the backs of the flogged. Bare stone, where snow was snatched away by climate change, is flayed skin. In my backyard, to witness the Wasatch Mountains is to ache.

Mountains speak. To listen, you must be as the mountains are: patient, persistent, still. If you try, you might hear, as John Muir did, the mountains calling. They call on us to be strong, to stand proud and resolute, to resist environmental destruction like the mountains resist the roadbuilders, the clear-cutters, and the miners. They’re calling on us to resist ecocide like mountains resist the geologic forces trying to drag them down. We have suffered, the mountains explain. We will continue to suffer until this madness stops. Yet, still we rise.

As massive as they are, the mountains’ wounds are only a fraction of the planet’s. Yes, the bad news piles up. The horrors intensify. The voice urging me to quit amplifies. But, with the Wasatch Mountains’ help, until all of Earth’s festering wounds have healed and only scars remain, I will not quit. I will do as the mountains do. I will rise and fight.

© Will Falk

Unrepentant Moon

by David Dodd Lee

David lives on Baugo Bay, a series of canals surrounded by wetlands, where the St. Joseph River and Baugo Creek meet close to the Indiana and Michigan border.

Because I live in some underbelly beyond the usual scrutiny

and in the morning the treadmill of my legs stands immobile

my mind spins drags with it the interminable flora and fauna

of my days the mating of snapping turtles the cormorant who

could never be a duck she hangs so low in the river she’s no

snake bird the anhinga but looks like the loch ness monster

at a meeting of concerned fisherpersons the vote is 23 to 16

to shoot bottle rockets at the cormorant consumer of sport fish

this submarine serpentWhat comes next unfortunately but an

important part of the record is I gotta pee but me not saying it

out loud O the persistence of perception the thing is I sing some

of the time coming out of the shower I smile as well at YouTube

I opine about my cat who caught and ate a fly just now ever sit

inside a quiet room prepared for the day wearing a fine button-

down shirt when a knock comes and you sigh and then open

the door Hello! my head’s still in the clouds I keep dreaming

I’m floating downriver when I should be updating my CV

the committee for killing fish-consuming birds tilts their brows

leeward as the commissioner of overreach bends his brow

windward says Devilish Bird! I say soto voce there are enough

fish to go around What was that? Who just spoke up against me?

and the most birdlike in the group gaze out the newly installed

clerestory windows God knows I drift in the raft of my bed

sometimes until afternoon my fingers dancing over keys

I slide from under the covers wondering about the day’s

marriage to form until an emerging narration is squelched good

riddance so I find a canvas tacked to the wall draw a large circle

with a Conté crayon this is the portal through which I enter

the tunnel of absolute time the non-thinking pulse of electrical

containment the beauty that’s not reasonable the diastolic

release from the evening (I’m still typing) sometimes unto

the wind which roars like an unrepentant moon through the

river valley words that crumble or topple into the river where

the cormorant shrugs says in an unplaceable accent Could y’all

just leave me in peace, please does a deep dive underwater

pops up a hundred feet downriver the size now of an insect lost

in distance my face still protected by a metaphysical awning

love of all bird life love of the mystery of steadfastness without

aim or contrivance followed by a whew or a long pleasing sigh

I may now make my way out to the drinking place the eating

place where I’ll order the Brussels sprouts and wax rhapsodic

for some hours with friends who agree Let the goddamn birds be!

© David Dodd Lee

Eli the Lamb,

Lower Longley, Tasmania

by Rafaella Del Bourgo

Rafaella lives between the coastal hills and the San Francisco Bay with her husband and one spoiled cat. Along the back of their property line, a row of Italian cypresses plays host to birds and squirrels. Underneath this urban neighborhood runs Potter Creek.

Monday morning, the parents at work,

two boys at school, Eli kicks down

one side of his pen,

arrives to rear up and clack, clack, clack

on my kitchen door.

I take my knitting outside,

sit on the sun-warmed boards of the back porch.

Our black cat curls in a basket

of colored balls of yarn.

Eli, brambles in his white coat,

heaves a most unsheep-like sigh,

lies down, head in my lap.

Before supper,

the ten-year old will come rushing into the yard.

Could I have my lamb, please?

stretching his skinny boy arms into the dusk.

I will heft Eli onto my right hip,

take the boy’s hand, trudge up the mountain

where Eli will be left,

penned up once again in solitude.

But right here, right now,

in a nearby blue gum,

galahs have stopped their screeching,

preen pink feathers in the filtered light.

And, peering from around the woodshed,

a family of grey kangaroos

completes this moment of grace:

black cat in a basket,

fat lamb with his head on my lap,

the wool blanket I’m knitting

partly covering his face.

© Rafaella Del Bourgo